By Ben Watson

The bloody battle to wrest Mosul from ISIS was the world’s largest military operation in nearly 15 years.

Here’s how Western-backed Iraqi soldiers helped break the Islamic State’s grip on a city of more than 1 million people — and what we can learn from it.

The Mosul offensive began on October 17, 2016, when a variegated body of more than 100,000 troops—local volunteers, regular soldiers, elite Iraqi and Western special forces—collapsed on the country's second-largest city. The force, believed to overmatch ISIS 10-to-1, moved under the cover of airpower provided by a half-dozen nations.

Advancing from the south, east and the north, Baghdad and its allies needed just 14 days to make it to Mosul’s doorstep. Iraqi special forces raced about 15 miles in those two weeks, and became the first to knock on that door. But such large-scale, coordinated assaults would prove much more difficult in the months to come.

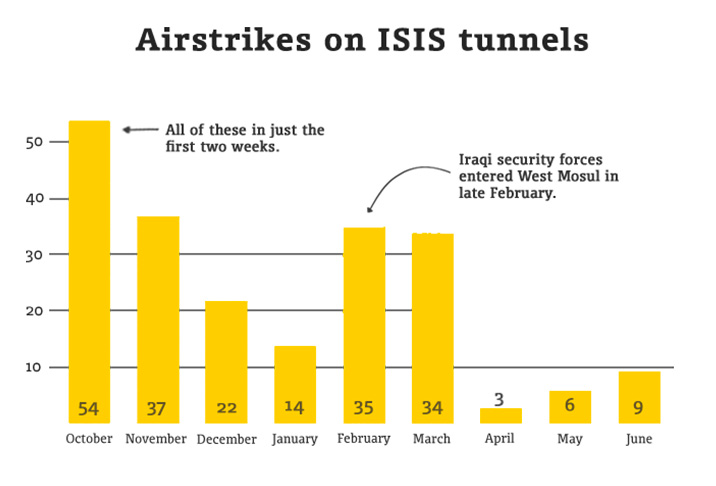

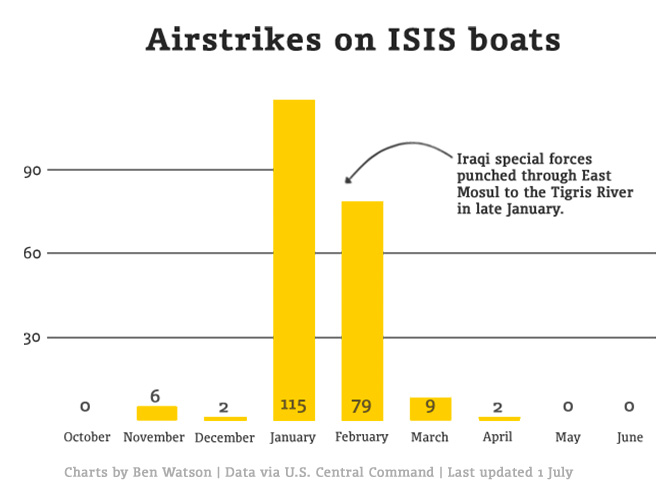

The assault on Mosul proper revealed an enemy well-prepared to grind down an attacking force. ISIS fighters used tunnels and street-spanning canvas overhangs to hide their movements. They set up artillery — both conventional and improvised. They armed a small fleet of boats for riverine combat. Most forbiddingly, ISIS laced the city with car bombs and the means to replace them.

“A lot of VBIEDs,” said the coalition's Deputy Commander, Brig. Gen. Rick Uribe, referring to vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices—what some in the military have termed bluntly "very big improvised explosive devices." “Particularly in November and December, which is when we finally got into the urban side of the city.”

Those car bombs soon were exploding at the punishing rate of five per day. “Then you had indirect fire that ISIS was using against our Iraqi Security Forces,” Uribe said.

Stuff like mortars and rockets—some stolen from Iraqi Army stocks, some manufactured from scratch. “It really was inaccurate. But they just were putting a bunch downrange,” said Uribe.

ISIS also continued to use suicide bombers, including many more children, terrorism scholar Charlie Winter noted in an exhaustive analysis of ISIS suicide operations through February. The trend would continue through the month of June.

In early November, Iraqi special forces broke through to East Mosul, where the Islamic State’s resistance stiffened markedly. The use of suicide car bombs rose steadily, as did coalition airstrikes on more than 100 ISIS factories producing them.

But the advance also yielded troves of intelligence. Iraqi troops seized the TV station and began digesting new information on car-bomb factories, artillery caches and a new weapon: armed off-the-shelf commercial drones.

By 2016, many militant groups had already put consumer drones to use for surveillance and reconnaissance, but the battle for Mosul marked the first use of armed drones by a nonstate actor. And even as ISIS was pushed from East Mosul in January, their drones grew deadlier.

It was also an easy tactic to copy.

Within weeks, Iraqi federal police had armed drones of their own. Like the ISIS versions, these were rigged to drop 40mm grenades fixed to badminton-like birdies that steadied the munitions as they fell.

The January 24 liberation of the city's eastern side marked the battle’s halfway point, and the coalition took a few weeks to regroup. The next phase would push across the Tigris River, whose bridges had been largely disabled. (See a detailed map of damage to Mosul's five bridges by December 5, via Stratfor, here.)

Coalition leaders used the time to review some of the more glaring tactical successes and shortcomings, said David Witty, a retired Green Beret colonel who now teaches at Norwich University. Witty, who advised Iraq’s Counter-Terrorism Service, or CTS, has published a report on Iraq’s Golden Division (also called the "Golden Knights") special forces for the Brookings Institution.

“There were a lot of mistakes made there in the first phase of the battle,” said Witty. “One of the big mistakes that was made early was that the counterterrorism service was really the only force to enter into East Mosul.”

For Baghdad, that was both a blessing—that the CTS advanced so far so quickly—and a curse, because the coalition began to rely on the special-purpose force to lead the charge. And oftentimes, alone.

“The counterterrorism service was set up to be an elite special operations unit,” Witty said. “You don't tell a Ranger battalion or a U.S. special forces battalion to go out and clear a city. That’s what you have a regular army for. The counterterrorism service, like the name implies, was an elite counterterrorism unit which is going to conduct precision range hostage rescues ambushes. It was never designed to be used the way it's been used now.”

The Golden Knights “fought in East Mosul by themselves for a good month while the other units were still outside of the city—the Iraqi army, the Iraqi federal police. It wasn't really until December when the other axes opened up and you had the Federal Police moving in, and the Iraqi army in, and they made some good progress.”

The pause appears to have given Iraqi officials time to absorb at least one important lesson.

“When they attack ISIS on multiple axes and have multiple advance routes, they’re successful. But when they only have one, it turns into a meat grinder,” Witty said. “It usually doesn’t work out, because ISIS is able to concentrate their best fighters and all their combat power on just that one axis. And that's a mistake that was made during the first half of the battle.”

In March, coalition forces began their attack on Mosul’s Old City, where ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi had first announced the caliphate in mid-2014. It’s a dense and difficult area to assault. General Uribe said this was well-understood by Iraqi and coalition planners.

“This would be a challenging fight for any force,” he said. “We knew that that was gonna be the case. Old Mosul, it’s just a different landscape. It’s very tight. Vehicles can’t fit in there. It’s a dismounted fight.”

Eight months of airstrikes largely leveled Mosul's Old City:

“West Mosul is much more difficult is because it's such a compact battle space and there's so many people, the streets are narrow, and of course there's been civilian casualties, no doubt about that,” Witty said.

Coupled with ISIS' use of human shields (see, for example, here and here), these factors turned the advance into a bloody weeks-long stalemate, with thousands of civilians caught in the middle.

The coalition's deadliest strike of the ISIS war to date took place on March 17 in al-Jadida district, West Mosul. Iraqi forces called in an airstrike on two snipers atop a building, which once hit, triggered an enormous explosion that killed more than 100 Iraqis.

The airstrike on al-Jadida marked a deadly turning point. The coalition reduced the frequency of airstrikes on suspected VBIED factories, though officials continue to stand by the overall conduct of the air war in the Mosul offensive.

"I don't think you've seen another camapaign in a long time with the level of precision that we've been able to accomplish here in striking the right target with the right weapon at the right time," Uribe said.

But the bulk of the fighting has taken place on the ground, and under historically dangerous conditions, Uribe said. “When is the last time that any major army has fought in an environment like this? I would offer it’s probably been in World War II.” Others have suggested the 1990s battles for Grozny, Chechnya, and 1968's assault on Vietnam's Hue City—but with caveats.

Witty suggested the 1942 battle for Stalingrad as a possible parallel. But, he added, “The thing that really makes this different is that the Iraqis are really taking a lot of care to try to protect as many civilians as they can and as much infrastructure as they can. And, of course, those those weren’t concerns to the Germans and Russians in the battles that they fought. So that's what kind of makes this unique and I think that was really kind of a hallmark in the battle of the east Mosul.”

By the end of May, the Iraqi Security Forces had been bogged down just 900 meters from the Nuri mosque for more than 40 days. On June 21, perhaps as a kind of last hurrah, the Islamic State group apparently detonated explosives inside and around the 12th-century Nuri mosque. Coalition troops managed to push ISIS into the final, remaining blocks of the Old City by July 7, one week after retaking the territory around the symbolic Nuri mosque.

On July 10, Prime Minister Abadi at last declared the liberation of Mosul standing alongside top Iraqi military officials inside the Old City — capping an offensive that stretched 266 days, longer than the battle for Stalingrad.

Since October, nearly one million Iraqis have fled their homes in Mosul and its surroundings, according to the UN.

However, the situation in the wider country is improving. “In Iraq, 1.7 million Iraqis are now back in their homes; no longer displaced, no longer refugees or migrants seeking to flee,” Brett McGurk, the U.S. envoy for the counter-ISIS campaign, said May 19. “That record is historically unprecedented in a conflict of this nature, and we give tremendous credit to the government of Iraq and local leaders who have worked cooperatively to stabilize local areas and return local populations.”

By March, the effort to free Mosul had killed more than 7,000 Iraqi civilians and wounded another 22,000, estimated Middle East observer Joel Wing, who has been tracking developments in Iraq since 2008. “The vast majority—6,340 of those killed and 17,124 of the injured—were civilians," Wing wrote.

How many of these deaths were caused by errant coalition munitions? By early July, Iraqis had accused the coalition of killing more than 7,000 civilians. The monitoring group Airwars said the number was more likely between 900 and 1,200. For their part, coalition officials said that its entire anti-ISIS bombing campaign since 2014 had killed just 603 civilians, including the 105 who died in the March 17 strike on Al-Jadida.

The offensive took a heavy toll on Iraqi security forces as well. Through mid-May, nearly 1,000 had died and 6,000 wounded, Joint Chiefs Chairman Gen. Joe Dunford said. And that’s an important, if often overlooked point about all of this, Witty said. “There's a lot of coalition air support a lot of advisers and ground trainers, but Iraqis are ones that are bleeding and dying every day. And I think that's what a lot of Americans don't understand.”

And ISIS itself? No one knows. Iraqi official estimates of the group's troop strength were all over the map; one officer claimed that more than 16,000 militants died in the battle for Mosul. But official U.S. estimates generally held that ISIS had begun its defense of the city with no more 6,000 ISIS fighters.

What comes next? As Iraq looks to rebuild, and tens of thousands of Moslawis return to their homes—or what’s left of them—ISIS is still holding onto territory south and west of Mosul.

“Other pockets of ISIS exist elsewhere in Ninawa, Hawija, and the western Euphrates River Valley of Anbar Province,” U.S. Defense Secretary Jim Mattis told reporters during his first ISIS war briefing on May 19. “We will continue to fully support the Iraqi Security Forces and Prime Minister Abadi's government in isolating and destroying ISIS throughout Iraq.”

And the future of Iran-Iraq relations? “That's really the million-dollar question,” said Witty. “The Popular Mobilization Forces—the Shi’a militias—they’ve become so important in this. Some of the popular mobilization forces are really independent, and work directly for Baghdad; others have Iranian advisors.”

Consider as well, he said, the Kurdish regional government and its willingness to cooperate with Baghdad. "Some will be opposed to it, of course. And then, so when that happens, where does that leave Iraq? Does Anbar Province want to break off, and set up its own its own country, since its majority Sunni? And does the rest of Iraq—Baghdad, really—become an Iranian rump state heavily influenced Iranian politicians and leaders? I think this is the beginning of a long, difficult process. Iraqi politicians have all been saying that the the phase that comes after Mosul is going to be harder than the actual Mosul because there's going to be a lot of hard decisions that have to be made.”

If the U.S. military has learned anything about Iraqi insurgencies over the past 15 years, it’s that violence will likely return to Mosul, as it has on occasion in Baghdad—which the group never seized.

And there are still other regions that Baghdad must wrest from ISIS.

On top of that is the ISIS presence in Syria, where an entirely separate large-scale operation has been progressing for months. The target: the group’s de facto headquarters in Raqqa. Beyond that, ISIS also maintains strongholds south of Raqqa in the Euphrates River city of Deir Ez-Zour, and some 200 kilometers west, around the ancient city of Palmyra.

Which is all to say: the battle for Mosul may soon be over, but the war against ISIS — already a generational conflict — is far from finished.

.

© 2017 | Defense One