In the Pentagon, senior U.S. military leaders often like to say that historically they are terrible at predicting the next war, while critics argue that generals constantly are planning for the last war.

Both may be true. Ironically, those same leaders have spent the last two years complaining that they are being forced to live in an era of too much uncertainty.

Why do Pentagon leaders think they can make uncertainty go away? The year 2014 could not have proven more unpredictable. Maybe it’s time to start planning for the unexpected.

The new era of global conflicts for which political leaders demand constant U.S. military intervention offers the Pentagon a new opportunity to stop fighting against the age of uncertainty and start embracing it.

These days, the “uncertainty” complaint refers to the budget, and to the automatic sequestration cuts lingering over budget writers’ heads. The mood around Washington this year is that the sequestration stunt’s time has passed. With the midterm elections behind them, a new secretary of defense on the way, and new political battles to be fought for something bigger (the White House) few seem eager to keep the sequestration fight alive. That will make a lot of folks happy: the arms industry, Defense Department purchasers, combatant commanders, and a few of those “J” divisions of the Joint Chiefs of Staff that plan for the future, at least.

But even with an agreed upon budget, there will come no added certainty to what the world will bring to the Pentagon’s doorstep this year. And that’s an uncertainty leaders in the Pentagon, Congress, White House, intelligence and law enforcement communities could do much more to anticipate and manage.

The year 2014 was supposed to the intermission. Remember? The time between eras, when the war in Afghanistan wound down and the military could get back to some fantasized version of itself that predated Sept. 11, 2001 – with training operations back at the bases, eased deployments, smaller forces and no more big land wars.

Instead the world gave chaos. At the Pentagon one year ago, not many people expected Russia to invade Ukraine, the Islamic State to take over half of Syria and Iraq, Western journalists to be beheaded one after another, Islamic extremists to attack civilians in Ottawa, Sydney and Paris, and half of the African continent to be embroiled in terrorism. By December, the mood around the Pentagon was one of exhaustion and exasperation at the never-ending stream of national security bad news.

Joint Chiefs chairman Gen. Martin Dempsey speaks at the Defense One Summit in Washington, D.C., on Nov. 19, 2014.

Each week brought another crisis, another possible deployment of U.S. firepower or “boots on the ground,” another political fight inside the Beltway, or another fight with adversaries outside of alliances. But inside Washington, little changed.

Institutions pivot as slow as aircraft carriers. That’s a luxury modern national security professionals can no longer afford. The institutions that fund, govern and oversee the U.S. defense machine remain organized in a way that barely resembles the current threat matrix it faces and, critics complain, operate too slowly as the world races by. Last year, incoming Senate Armed Services Chairman John McCain, R-Ariz., pledged to create a new subcommittee on cybersecurity. That a standing committee did not already exist was shocking to many.

Army leaders have said they wanted the post-war years to allow that service to become more “agile” and “flexible” for a new counterterrorism age. It’s an idea the entire national security community should consider for itself, too. Among the chief criticisms of President Barack Obama on foreign policy is that he was too reluctant to use U.S. military force of any kind anywhere because he is spooked by the big wars of Iraq and Afghanistan.

Critics like Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., (who is considering a run for the presidency) and allies like former Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak say Obama should have armed Syrian rebels and launched military strikes there sooner. Instead, Washington leaders spent months debating if new war powers were needed to strike in Syria, or Iraq, against the Islamic State group or anyone else. The Pentagon spent months to come up with even a plan to send a few hundred trainers into Syria, years after that war began.

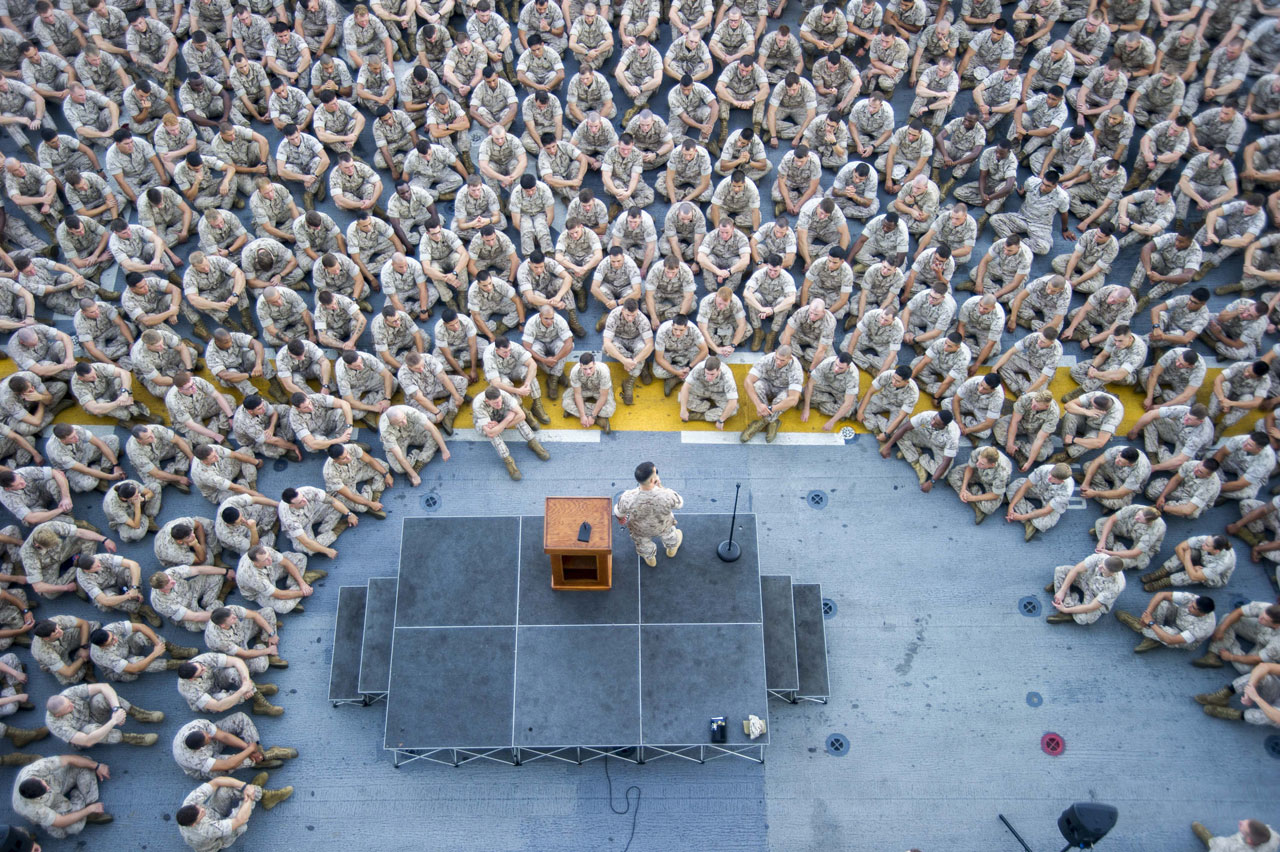

Then Deputy Defense Secretary Ashton Carter speaks to troops at Joint Base Elmendorf, Alaska, on March 21, 2013.

Others this week point to Yemen, whose capital is under siege by Houthi rebels after months of openly staging for such an attempt on the government, while the U.S. stayed mostly on the sidelines. Yemen has been collapsing on itself for years, but this weekend McCain blamed Obama for Yemen’s chaos.

Inside the military services that have to be ready to carry out the U.S. response to any conflict, planners are moving forward with some of their own changes so that they don’t have to wait for uncertainty. In 2015, there will be new chiefs of the Army and Navy. Until then, the Army is expected to win its request to scrap the downsizing plan it wanted one year ago, thanks to the high demand for rapidly deployable troops to the world’s hotspots. The Army also will proceed with a complete overhaul of its helicopters. The Air Force is pressing on with the F-35, with no alternatives at this point, while calling for more drone pilots. That service also will continue to mend after repeated scandals in its nuclear force and sexual assault issues. The Navy spent the winter finally scrapping its ship of the future, the littoral combat ship, or LCS, and rebranding it as an up-gunned frigate, while the service explores how to keep top personnel in the modern age. The Marines continue to be that “middleweight” amphibious force its leaders prefer, but the president and Corps leaders keep sending them deep into landlocked countries as tip-of-the-spear reaction counterterrorism forces. The new commandant is expected to lay out his plans within weeks.

Nobody wants more certainty about their futures more than the men and women in uniform. Congress and the president may finally move them beyond the sequestration era, easing fears in pocketbooks and at PXs. But the world certainly won’t be tipping its hand anytime soon. That means it’s up to the new stable of decision makers – from likely next Defense Secretary Ash Carter to McCain and the new Joint Chiefs to come – to figure out how the state of defense can remain one that is prepared for anything, anytime, anywhere. Because if past is prologue, that’s how often U.S. soldiers, sailors, airman and marines must be ready to fight in the new era.

Three years after leaving Iraq, the Army is officially back.

And an aggressive Russia means more American troops and tanks in Eastern Europe. With steep troop reductions still to come, many fear the force is at its breaking point.

In the final year of Operation Iraqi Freedom, the Army had more soldiers on active duty than at any point in nearly two decades. Now four years after leaving Baghdad, there are 62,000 fewer troops for a branch fighting back the Taliban, Islamic State, Ebola and Russian aggression in 2015.

The Army began the fiscal year with 508,000 active duty troops, but is in the middle of the steepest manpower cuts of all the services. After losing more than 30,000 each of the previous two years with the Iraq and Afghan wars winding down, another 18,000 will be gone by October to conform to congressionally mandated budget caps. Reduced bonuses, attrition and separation screening boards are expected to cover that loss.

It’s also cutting another six brigade combat teams — on top of the five it lost in 2014. All this makes many both in and out of the uniform nervous about what lies ahead.

“Thirteen years of constant war has broken parts of our force and put tremendous strains on especially our Army and our Marines,” outgoing Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel said Thursday at Fort Bliss, Texas.

“Using the average requirement of five support soldiers to support one combat soldier, the U.S. Army only has about 140,000 combat troops to close with and destroy the enemy,” retired Green Beret Maj. Rusty Bradley told Defense One. “We never received the number of troops needed to be successful in Afghanistan for this very reason — the Army is too damn small.”

Meanwhile, Army Chief of Staff Gen. Ray Odierno, who originally supported downsizing, has fought tooth and nail with lawmakers not to hollow out the force in the face rapidly proliferating threats across multiple continents. By late last year, Odierno said the downsizing was too much and signaled he’s already prepared to make his case again during the Pentagon’s posture hearings before Congress in the spring.

“My worry is based on how I view the world — and I’ve talked a lot about the velocity of instability is increasing significantly — that I don’t see a downturn in requirements,” Odierno said at the Defense One Summit in November. “So in my mind it’s about us talking with Congress and others about understanding the risks associated with it, and that they have to re-evaluate and review some of the decisions they’ve made.”

-01.svg)

There are around 55,000 U.S. soldiers deployed around the world. Another 80,000 are stationed in 150 different countries.

In early 2014, discussions of the Army’s future revolved around talk of a rebalance to the Pacific Command region where 2,400 soldiers are deployed, mostly in Japan. That’s since taken a backseat to the billion-dollar European Reassurance Initiative that pays for a battalion-sized Army unit training NATO allies. It also complements Odierno’s regionally aligned forces concept, which assigns Army units to particular combatant commands to build long-term relationships with local allies.

This year, soldiers from the 4th Infantry Division’s headquarters become the second stateside unit to be regionally aligned with European Command. They’ll keep that assignment for at least a year, replacing the nearly two thousand soldiers from the 1st Cavalry Division out of Fort Hood, Texas, that have been helping train allies in Poland, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania since September. Another 29,200 U.S. soldiers are spread across the continent. And the Army wants to more than double its 62 tanks and Bradley fighting vehicles staged in Europe by next January.

U.S. Army Rangers prep for extraction during training at Fort Hunter Liggett, Calif., Jan. 30, 2014.

There are also 2,000 soldiers split between Liberia and Senegal fighting Ebola in West Africa. And more than 10,000 U.S. troops woke up this New Year still in Afghanistan — most of that drawn from the Army. Meanwhile, hundreds of soldiers from the 1st Infantry Division are at Iraq’s Camp Taji this year training four battalions for combat against the Islamic State.

“We made assumptions that we wouldn’t be using Army forces in Europe the way we used to. We made assumptions that we wouldn’t go back into Iraq,” Odierno said of last year’s Pentagon posture hearings before Congress. “We are back in Iraq. Here we are worried about Russia again. So I think we should be very careful and mindful of the decisions we’re making.”

The Army has $120.5 billion this fiscal year to care for soldiers at 152 Army installations worldwide. Nearly half of that money — 47 percent — goes to paying troops who this year will receive their lowest raise in at least three decades.

-01.svg)

But even the lawmakers who passed the latest defense authorization bill worry the Army is going through too many changes too quickly, noting in the bill’s text, “Congress is concerned with the planned reductions and realignments the Army has proposed for the regular Army, the Army National Guard, and the Army Reserves in order to comply with the funding constraints under the Budget Control Act of 2011.”

Meantime, lawmakers want Army leaders to provide at least a half dozen reports ahead of the spring posture hearings. The controversial helicopter swap with the National Guard is on their radar. So is a full report on the divestiture of the armored M-113 family of vehicles. Also required: a progress report on the National Guard’s fielding of 10 cyber protection teams; and a progress report on Odierno’s regionally aligned brigade concept. That could be a tense, if also predictable, exchange — and one of his last as chief of staff. The 39th Army chief takes over in October. And the Army’s top enlisted man, Sgt. Maj. of the Army Raymond Chandler, welcomes his successor, Command Sgt. Maj. Daniel Dailey of the Army’s Training and Doctrine Command, on Jan. 30 at the Pentagon.

Congress is concerned with the planned reductions and realignments the Army has proposed.2015 National Defense Authorization Act

An AH-64 Apache from the 42nd Combat Aviation Brigade takes off near Tabuk, Saudi Arabia, April 12, 2014.

What does all this mean for those wearing the uniform? The officers and enlisted that Defense One spoke with expressed the same sense of duty and desire for high marks that they had when they joined years, and for some decades, ago.

“I think everyone is a little concerned about our future ability to deal with a conventional threat like Russia because we're drawing down,” one senior enlisted soldier said. “But I love serving, and that's the bottom line. For those of us with that mindset, we just want the resources to be able to do what the nation asks without half-assing it. We want the public to support us and care about what's going on with the country and world more than what's on reality TV.”

Among the National Guard, the Aviation Restructuring Initiative is being seen as the opening move to take away combat arms systems to meet the higher-profile active duty op tempo requirements. Meanwhile, it’s 2016 when the real fight plays out for the Guard. They, too, are downsizing from a 2013 peak of 358,000 down to 335,000. If the sequester holds through the next fiscal year, both the Guard and Reserves will have to drop another 20,000 each.

The answer is not for us to continue to send troops to fight other people's wars.Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel

The bottom line: A leaner Army will have to do. Last week at Missouri’s Whiteman Air Force Base, an airman asked Hagel if he sees the anti-ISIS air campaign progressing to more U.S. boots on the ground in Iraq. "The answer is not for us to continue to send troops to fight other people's wars," he said.

After two large ground wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the military is rethinking its scale and purpose.

But the Navy hasn’t skipped a beat. With the pivot to Asia and the Pacific, increasing tensions in the Gulf and new threats in Europe, including the Black Sea, the Navy’s mission has changed but hasn’t slowed down.

With about 100 ships at sea, the Navy is as busy as it’s ever been. And they’re looking to rekindle their special relationship with the Marines and bring amphibious operations back to the forefront. “They’re doing everything from conducting strikes in Iraq and Syria, to combatting Ebola in Africa, to exercising with our partners and friends to ensure freedom of navigation in the Pacific,” Navy Secretary Ray Mabus said recently.

“As we have drawn down from two land wars our sister services talk about their ‘re-set’ and their troops coming home. Well there are no permanent homecomings for Sailors and Marines. For 239 years they have deployed continually to keep America’s adversaries far from our own shores. They deploy not only to fight and win our nation’s wars, but to deter our potential enemies and prevent wars from happening,” Mabus told the Surface Navy Association earlier this month.

Mabus pointed out that once the decision was made to conduct air strikes against the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, the USS George H. W. Bush was there in 30 hours.

The Navy is also working on mobile landing platforms, such as the Afloat Forward Staging Base, as a transfer point between larger ships and small landing crafts.

And cyber is demanding more attention. The Navy is working on the CANES program, the Consolidated Afloat Networks and Enterprise Services, which will equip every ship in the fleet with a standards-based network.

Advanced networking systems will prove ever more vital in the coming years. The future of combat will require ever more drones, including networked small boats working together autonomously like the Office of Naval Research demonstrated last year. Even traditional naval aviation flying of off aircraft carriers is facing a different future with prototype drones like the X-47B looking to displace manned aircraft.

The increasingly globalization of terrorism, as seen by the attacks in France and other threats across Europe, and the recent aggression of Russia, means that the Navy is in more demand than ever. But there are challenges not only abroad, but at home. Budget cuts still threaten the Pentagon, with another round of sequestration on the table.

“Looking ahead to 2015, the state of the U.S. Navy concerns me,” Rep. Randy Forbes, R-Va., told Defense One. “Although the American Navy remains the finest naval service in the world, six years of reckless budget cuts have shrunk our fleet to one of its smallest sizes since the First World War.”

Much of the Navy’s resources are tied down with controversial programs like the Littoral Combat Ship, the Zumwalt class destroyer, and the F-35 fighter. The LCS is over budget and widely seen as under-gunned, the Zumwalt is so expensive that procurement is held to a mere three ships, and the F-35, despite being the most expensive weapons program in history, has become a running joke.

“At present, the service faces alarming shortfalls in critical classes of ships and in the funding required to fulfill its existing shipbuilding and modernization plans. Meanwhile, sustained demand for the capabilities our Navy provides have forced the service to adopt questionable ship-counting rules, and force its remaining ships into ever longer deployments, placing additional strain on our hardware and — importantly — on our sailors and their families,” Forbes said. “As is their tradition, the dedicated men and women of the Navy are making do, but I am alarmed by the potential damage these trends could do if they are allowed to go unchecked.”

The Navy is looking to be leaner and meaner, and not just because of budget cuts. The fleet is strong, even though the wars have officially ended and budget cuts remain the status quo, Mabus said. “In 2014, we launched nine new ships and by the end of the decade our plan will return the fleet to over 300 ships.”

“And we haven’t done this at the cost of naval aviation. During my time in office we have bought 1,300 aircraft. That is 40 percent more than the Navy and Marine Corps contracted in the five years before this administration took office,” he said. “I know some people are claiming it, but our fleet is not in decline.”

The USS Nimitz prepares to launch fighter jets for flight operations for Operation Inherent Resolve, on Dec. 8 2014.

Still, there is plenty to worry about.

“The situation the Navy faces today reflects the polar tensions of the major actors within DOD,” Ret. Vice Adm. Peter Daly, CEO of the U.S. Naval Institute, told Defense One. “The combatant commanders ‘demand’ assets and the military services ‘supply.’ The combatant commanders have a regional focus, relatively short horizon, and are fiscally unconstrained for force demand. The Chief of Naval Operations and other service chiefs have a global focus, longer horizon and are fiscally constrained for force supply. When demand exceeds supply, all roads lead to the Secretary of Defense who makes the final decisions. It is he as the civilian leader who signs the important deployment orders. You get where we are today when, year on year, SECDEFs say ‘yes’ to force demand, without prioritizing and providing the resources for the high demand forces.”

An F-35C Lightning II carrier variant Joint Strike Fighter is prepared for launch aboard the aircraft carrier USS Nimitz, on Nov. 4, 2014.

"When supply exceeds demand, SECDEF should either say “no” to the extra/extended deployments or shift resources to increase supply. Otherwise, you overuse high demand platforms and overuse the people who man and sustain them," Daly said.

The size, the readiness, the psyche and the morale of the ground force is a joint issue we all ought to be concerned with.Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Jonathan Greenert

This is a time of transformation for the Navy and the Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Jonathan Greenert will be replaced. Greenert, speaking at the Brookings Institute last fall, said the Navy is working with all of the services to combat the threats and needs of the future.

“The size, the readiness, the psyche and the morale of the ground force is a joint issue we all ought to be concerned with as we do this. We've got to do it very carefully,” he said.

The Air Force has flown the majority of the more than 15,600 missions against Islamic State militants in Iraq and Syria since last August.

It has also conducted the bulk of the more than 1,700 air strikes against the group also known as ISIS.

Air Force intelligence from drones, satellites and manned aircraft have been instrumental in nearly every mission over these past five months. Air Force tankers have refueled U.S. and coalition warplanes around the clock. And when strikes expanded from Iraq to Syria in September, the stealthy F-22 Raptor, an expensive fighter jet in the fleet for a decade, was used in combat for the first time to evade Syrian air defenses.

The airstrike campaign against ISIS has shined a light on how the Air Force has reorganized itself over the past decade, allowing it to perform more missions at a faster pace using a mix of old and new aircraft.

“I think a lot of what the Air Force is involved with is kind of behind the curtain these days,” said Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Mark Welsh.

Whether it’s B-2 stealth bombers flying halfway around the world from their home base in Missouri to drop inert bombs on a training range in South Korea, B-1 bombers flying from South Dakota nonstop to strike targets in Libya, moving a Patriot missile defense battery to Turkey or transporting a brigade combat team to Romania, “Nobody ever asks: Can you get it there? It’s just assumed that we can,” Welsh said.

The general is quick to point out that on any given day, 200,000 U.S. Air Force airmen are directly supporting regional military commands around the world.

And looking to the future, Welsh sees the Air Force remaining focused on its five core missions: air and space superiority, intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance, mobility, strike and command and control.

“What’s changed over time is how we do them,” Welsh said. “What’s changing now even more dramatically is which domains we do them in and from.”

The Air Force has shrunk dramatically over the past 25 years. For example, it had 188 fighter squadrons during the Operation Desert Storm in the early 1990s. That number of squadrons has fallen to 54 today and is on its way down to 49 in the coming years.

F-15 Eagles fly over the wildland fires in Southern Oregon following a routine training mission.

“All of the excess capacity is gone,” Welsh said. “All of the stuff that could afford to be not completely ready to do the job is no longer in the service.”

Welsh warned at a briefing last week that the service cannot shrink below the 315,000 airmen it has today.

“We cannot go any lower,” he said. “We are getting too small to succeed, as opposed to too big to fail. We're at a point now where we are undermanned in many career fields because we've taken people out of them to put in other areas to shore up those areas.”

The concept of “tiered readiness,” where some squadrons are more battle ready than others has been abandoned. “Our Air Force is either ready or it isn’t,” Welsh said.

Right now, the service’s fleet is old, with some tankers, bombers, trainers and intelligence planes dating back to the 1950s and 1960s. Welsh notes that nearly a dozen fleets of aircraft “qualify for antique license plates in the state of Virginia.”

In an attempt to save money for new aircraft and equipment, the Air Force has taken the dollars it has saved from retiring aircraft and eliminating squadrons and has invested it in new weapons.

In the coming years it is planning to buy new planes across all of its aircraft fleets. And without those new planes, the Air Force will become “not viable in combat in the next 10 to 15 years,” Welsh said.

The Air Force has made the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, a new long-range stealth bomber, and the KC-46 aerial tanker its top three acquisition priorities in the coming years.

“From an operational analysis viewpoint, you have to recapitalize those capabilities or you can’t win the big fight 10 years from now,” Welsh said.

Older planes, like the F-15, will get new radars to improve its targeting and ability to counter more modern enemy aircraft. Stuff that Air Force leaders want, but have not been deemed essential, have been axed.

“We cut 50 percent of our modernization programs to operate within our topline [budget number],” Welsh said.

A senior NCO marshals one of the 934th Air Wing's C-130J after it landed, on Sept. 12, 2014.

The Air Force has created an acquisition plan that is “fundable, executable and it’s practical,” Welsh said. “It’s not the one we’d like to have, it’s the one we have.”

Still, some budget-cutting moves, such as retiring the A-10 Warthog – an attack plane that started flying in the 1970s, but has been instrumental in providing cover for ground troops over the past decade – have not been well received in Congress. The jet has recently been deployed to assist in air strikes against ISIS.

But Air Force leaders say they must retire older planes like the A-10 and U-2 spy plane so they can divert money toward new, high-tech aircraft built for future wars.

Frank Kendall, the Pentagon acquisition chief, said Air Force planners are “striking a reasonably good balance” by investing in the F-35, a new bomber and KC-46 tanker for the future.

Despite budget cuts across the Pentagon in recent years, the Air Force has managed to start buying a broad range of new aircraft.

The KC-46, a jetliner that could refuel military aircraft in flight, made its first flight late last month. Sikorsky has started work on a new fleet of combat search-and-rescue helicopters. In 2015, the Air Force is expected to select either Northrop Grumman or a Lockheed Martin-Boeing team to build a new, long-range stealth bomber.

Over the past decade, the focus on operations in Afghanistan, Iraq and other parts of the world has diverted funding from Air Force infrastructure projects, specifically updates to training ranges, testing equipment, space launch facilities and simulation equipment, Welsh said. To make sure airmen are trained for future missions, it must “reset” itself in some key areas.

“We will effect long-term combat capability in a significant way if we don’t reset in terms of consistent and persistent investment in the types of critical mission infrastructure that we need to beef up,” Welsh said.

It will take a decade or two to update the Air Force’s nuclear facilities, an area of increased focus following a high-profile scandal when it was revealed officers cheated on proficiency tests.

It’s not the one we’d like to have, it’s the one we have.Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Mark Welsh

Maj. Justin Robinson flies the 56th Operations Group flagship F-16 Fighting Falcon March 10, 2014, as he escorts the first F-35 Lightning II to its new home at Luke Air Force Base, Ariz.

Training ranges now cannot simulate enemy threats expected in the next 10 years, Welsh said. The Air Force has made advances in training over the past decade or so, allowing pilots in simulators to train with pilots actually flying planes, a concept that the service calls, live, virtual constructive. Simulating threats against high-tech, fifth-generation aircraft, like the F-22 and F-35, will be difficult.

Instead of live, virtual constructive … we need to think about how do we take that training environment and make it virtual, constructive and live.Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Mark Welsh

“One of the things I think we’ll find … is that you’re not going to be able to train fifth-generation capability against a future threat on a live range,” Welsh said. “You just won’t be able to afford to keep it updated and current at the same pace of technology.

“Instead of live, virtual constructive … we need to think about how do we take that training environment and make it virtual, constructive and live,” he said.

But the big wild card facing the Air Force, and the rest of the Pentagon for that matter, is whether federal spending caps remain in place in 2016.

“Budget issues are going to affect the Air Force’s ability to buy everything else they need to,” said Mark Gunzinger, an analyst with the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments.

If there’s a bumper sticker for the Marine Corps these days, Marine officials will tell you it’s “innovate, adapt and win,” a cocky but perhaps accurate characterization of a Corps in transition.

While there may be lingering doubts about the wisdom of ending two large ground wars, it’s clear the political appetite for ground forces is on the wane, and that’s allowed Marines to begin to return to their maritime roots in an attempt to distinguish themselves from the other service with ground forces, the Army.

Marines are now refocusing on amphibious operations, reacquainting themselves with the Navy and, in true form, attempting to do more with less: fewer ships, a smaller force and less money.

“I would say that we are living the new normal today,” said Lt. Gen. Kenneth Glueck, Jr., head of the Corps’ Combat Development Command, in an interview with Defense One.

After more than 13 years of war, the Corps faces a new period of fiscal austerity, a smaller force and a scramble, like all the services, to be relevant. Instead of maintaining thousands of Marines in landlocked Afghanistan, which was considered counter to the Corps’ sea service traditions, the focus now is on smaller, more forward-deployed forces ready to respond to contingencies.

“The Marines play as big a role in that as any of our services do, because you were always on that cutting edge and you were always on that front edge as your relationships develop and as you have to reach out,” outgoing Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel told Marines aboard Marine Corps Air Station Miramar, Calif.. “We're going to get you back to that.”

The Marines are now being led by commandant Gen. Joseph Dunford, installed in October, and he is expected to release his “commandant’s Guidance,” an annual ritual for the Corps’ top Marine, in coming weeks. It’s not expected to change the direction of the Corps in any dramatic ways, but may emphasize enduring themes, from adapting and innovating to decentralizing planning and empowering junior leaders across the service.

Dunford may not work behind the famous saloon doors of the commandant’s office in the Pentagon’s E-Ring for long. Dunford, who returned from nearly two years as commander of the war in Afghanistan, remains a leading candidate to become the next chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. The current chairman, Gen. Martin Dempsey, is expected to retire sometime later this year.

For now, Dunford will to continue lead the Corps to a place where it is most relevant given the budgetary environment in Washington and the security environment around the world.

Under the previous commandant, Gen. Jim Amos, there was a distinct effort to position the Corps as relevant to those very security challenges, which include the threat posed by the Islamic State across the Middle East but also to respond to raw sensitivities among many nations in the Pacific or security threats in Europe.

Marines conduct machine gun range training in D'Arta Plage, Djibouti, Nov. 12, 2014.

In 2013, the Corps rebranded its cornerstone concept, the Marine Air-Ground Task Force, with the creation of the Special Purpose Marine Air-Ground Task Force for Crisis Response, a so-called MAGTF specifically designed to respond to contingencies requiring accelerated response times. The first one was created and deployed to a base in Moron, Spain. Though planned long before the attack on the U.S. diplomatic facility in Benghazi, Libya in 2012, Corps officials have said the task force could be an effective first responder in a similar attack in the future.

And as the big land wars ended and the appetite for large ground forces waned, the Special Purpose MAGTF was part of the answer to how the Corps could contribute to U.S. global security and the response from combatant commanders has been positive and the demand for more of the task forces unyielding.

“We’ve always had special purpose MAGTFs, but this is the first time where we’ve put some legitimacy behind it,” Glueck said.

The Marines play as big a role in that as any of our services do.Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel

But there are limits to what the Corps can do given the amount of resources available to it or its sister service, the Navy. Ships, or the lack thereof, are the best example of that. The current availability of Navy ships doesn’t satisfy the Marine requirement for amphibious ships or so-called “amphibs.”

Such is the demand for ships that Marine Expeditionary Units used to ride on amphibs along with what’s called an Amphibious Ready Group. These flotillas of ships used to deploy and steam generally in concert; now the ships are split up for different missions, or “disaggregated,” as Corps officials like to say, because the Navy can’t afford to keep them grouped for operations.

According to one recent study, conducted by the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ Maren Leed, the demand for amphibious ships in 2015 was more than 70, even as the ships the Navy was able to provide was only 33 at any one time.

As a result, the Corps is exploring alternative ways to put Marines closer to where they need to be in order to respond to crises, be it an embassy under attack, or for broader and less time-sensitive forms of engagement, like the kind of relationship-building known as “Phase Zero” that Marines also conduct.

Marines are looking at the model provided by Special Operations Command’s use of the Ponce, an old Navy ship that has been “repurposed” as a floating forward operating base for the specialized units. Other alternatives to expensive Navy amphibious ships include what’s known as an MLP, or Mobile Landing Platform, which are cheaper and more available than traditional combat ships. Such approaches eliminate the inherent complications of basing units ashore, where political sensitivities within the nation hosting the base can undermine the mission, and also where they can be further away from where they need to be. The Corps is studying how best to integrate forces deployed on such alternative platforms with those ashore and on more traditional Navy combat ships.

All of this comes at a time when the Corps and the Navy are touting their newly renewed, close relationship. Marine and Navy officials say the relationship between Amos, the former Marine commandant, and Adm. Jonathan Greenert, the Chief of Naval Operations, grew closer and has begun to permeate across both services. And there’s no reason Dunford won’t continue that relationship. That’s a welcome change and one Corps officials hope endures.

“Usually, we’re the red-headed step-child of the Department of the Navy,” one Marine official said.

It’s not going to be how it was in the past, no Iwo Jima or Tarawa.Lt. Gen. Kenneth Glueck, Jr

Marines practice close combat drills at the Western Barry M. Goldwater Range near Marine Corps Air Station Yuma, Arizona, June 3, 2014.

Corps leaders like Glueck say that although the Corps is returning to its maritime roots, these are not your father’s amphibious operations. Corps planners are focused on exploiting enemy forces’ gaps and seams, but that means amphibious units must plan on inserting themselves in places a much farther distance away. “It’s not going to be how it was in the past, no Iwo Jima or Tarawa,” Glueck said. “We’re going to be utilizing different concepts.”

In the meantime, the Corps is still shrinking in at least two ways – its size, and its budget. It will re-size to a force of 182,000 by the end of 2016, from a high of 202,000 just a few years ago. That’s not as small as it was at the time of the attacks on 9/11, when it was about 172,000, but still smaller than it’s been for many years and making it that much harder for Corps leaders to meet the demands being placed on them.

At the same time, the Corps is focused on balancing between competing needs: “near-term readiness,” the need to make sure forces and equipment are prepared to get the call to deploy, and long-term modernization of the force, that equipment, and infrastructure across the force. Budget cuts over the next year could mean more tough choices: the Corps could lose the funding for as many as two MV-22 Osprey squadrons and three infantry battalions, which would have, in the words of one Marine official, “some pretty immediate and drastic effects.”

What do you think?

Let’s continue the conversation on Twitter at #StateofDefense.

And get the latest from Defense One delivered right to your inbox every morning by signing up for our daily newsletter.