A Predator drone with the 163rd Reconnaissance Wing is shown during post-flight inspection at dusk from Southern California Logistics Airport, formerly George Air Force Base, in Victorville, Calif., Jan. 7, 2012. U.S. Air Force Photo by Tech. Sgt. Effrain Lopez

Obama’s New Drone Export Rules Won't Sell More Drones

President Obama’s new drone export rules are little more than a mix of existing rules reflecting an outdated perspective on these important weapons.

When the U.S. announced last month a new policy governing the export of U.S. drones, news outlets overwhelmingly declared a coming flood of U.S. military drone sales around the world. Go read the government news release, however, and you’d be hard pressed to reach these conclusions – and for a good reason.

The president’s policy is not new, will not lead to rapid proliferation of U.S.-made drones and does nothing to clarify the confusion about why drones should be treated differently from other weapons systems. What the policy does is build on the precedents of past, case-by-case decisions regarding drone exports. The U.S. has sold military unmanned aerial vehicles, or UAVs, including armed drones, to several nations since the early 2000s. In fact, U.S. sales of military drones goes back even further to the 1970s with sales of Firebee drones to Israel. Modern examples are numerous. The Italian Air Force acquired Predators in 2004 and the more advanced Reaper derivative starting in 2010. Both Italy and the U.K. operate armed Reapers that they purchased from the U.S. There are ongoing discussions with Japan, South Korea, Australia and others on possibly selling the advanced Global Hawk. On the opposite end of the size spectrum, the U.S. has sold the hand-launched Raven to partners ranging from the ironclad – U.K. and Canada – to the less stable – Yemen and Pakistan.

If last week’s announcement didn’t constitute a truly new policy on drone exports, how should one view these rules? To paraphrase The Who: Meet the new policy, same as the old policy.

For some time, the various entities within the U.S. government that play a role in the export of these weapons—the Departments of State, Defense and Commerce, along with the National Security Council—have been working to articulate a unified policy to govern drone exports. The resulting announcement reflects the unity that was found, the substance of which was essentially an amalgamation of existing policies and practices. That unity has value, providing a common U.S. government starting point for all drone sales. In addition, it offers a set of principles that the U.S. can use with other nations when attempting to control the transfer of drone technology, especially in more advanced models. In fulfilling these purposes, the policy may well be worthwhile.

It is not likely that the policy will lead to significantly increased exports of U.S.-made drones. The change in no way lowers the significant hurdles to exports established by the U.S. Conventional Arms Transfer Policy, the Arms Export Control Act, the Foreign Assistance Act, and the Missile Technology Control Regime, or MTCR. In the case of the MTCR, drones with a range greater than 300 km and a payload above 500 kg – such as the Predator, Reaper, and Global Hawk – are subject to strict controls including “strong presumption of denial” for export, a barrier only lifted in “rare occasions.” Although the new export policy promises a faster decision timeline, drones, especially the larger and more advanced ones, will be subject to enhanced controls including agreements covering “principles for proper use,” increased security, and close end-use monitoring. This does not sound like a policy permissive of or conducive to exporting U.S. drones under most circumstances, and especially for military use.

What’s disappointing about the policy, however, is that it is so focused on range, payload and weapons capacity that it in no way distinguishes what makes drones new and different. Many manned assets, including relatively unsophisticated ones, can perform all of the same functions of a drone. But under the new policy, those functions would trigger the highest degree of controls if the cockpit were simply removed. In fact, converting such assets to be “optionally” manned is an increasingly achieved objective. The key differentiator for unmanned systems from similarly capable manned systems is their degree of autonomy from direct human control. Here the policy sets absolutely no standard, bypassing what many drone observers would agree is a critical issue that merits careful review.

Several additional questions also remain unanswered. The artificially created distinction between commercial and military drones in this export policy has not been clearly explained and may become increasingly less relevant as the technology develops. Military drones provide persistence with a wide variety of sensors, yet this is becoming increasingly available commercially. While military drones may be over-engineered to better survive combat, commercial ones will offer an 80 percent solution in almost all missions.

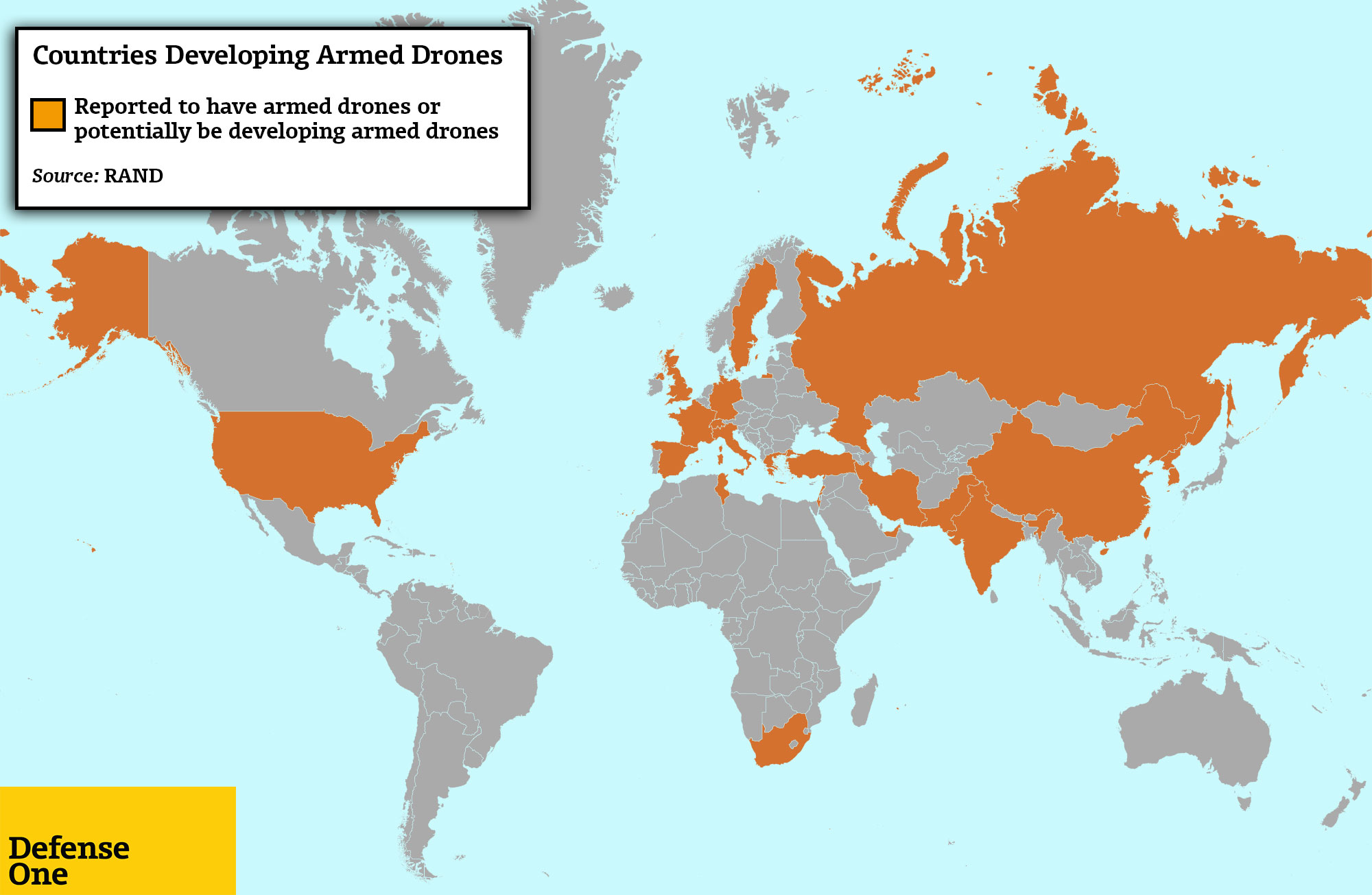

Obama’s new policy also likely will not abate drone sales by other nations such as Israel and China. Israel was the world’s largest exporter of drones from 2005 to 2012, outselling the U.S. by approximately $1.5 billion, according to a 2013 report by the market research firm Frost and Sullivan. The Chinese have moved incredibly swiftly into the market, producing and selling a staggering array of systems to a wide range of buyers. China has sold their Wing Loong drone, in essence a Chinese knock-off of the Predator, to Saudi Arabia. Many were caught surprised when an armed Chinese CH-3 drone reportedly crashed in Nigeria, in January.

The U.S. drone export policy takes an important first step providing a foundation from which policy can evolve. In many ways, however, it represents a missed opportunity to establish a truly new and enduring policy. And despite arguments to the contrary, it likely will not result in a wave of new U.S. drone exports. In fact, over time, it may become more restrictive for exports than its authors ever intended. U.S. officials need to develop an approach to drones that truly addresses the importance of this technology to U.S. national security, the arms trade today and in the future.

NEXT STORY: Over There, and Overlooked