Mike Heywood via Shutterstock

Why There Will Be A Robot Uprising

The bad news is that the robot uprising is likely. The good news is that it’s not too late to stop it. By Patrick Tucker

In the movie Transcendence , which opens in theaters on Friday, a sentient computer program embarks on a relentless quest for power, nearly destroying humanity in the process.

The film is science fiction but a computer scientist and entrepreneur Steven Omohundro says that “anti-social” artificial intelligence in the future is not only possible, but probable, unless we start designing AI systems very differently today.

Omohundro’s most recent recent paper , published in the Journal of Experimental & Theoretical Artificial Intelligence, lays out the case.

We think of artificial intelligence programs as somewhat humanlike. In fact, computer systems perceive the world through a narrow lens, the job they were designed to perform.

Microsoft Excel understands the world in terms of numbers entered into cells and rows; autonomous drone pilot systems perceive reality as a bunch calculations and actions that must be performed for the machine to stay in the air and to keep on target. Computer programs think of every decision in terms of how the outcome will help them do more of whatever they are supposed to do. It’s a cost vs. benefit calculation that happens all the time. Economists call it a utility function, but Omohundro says it’s not that different from the sort of math problem going in the human brain whenever we think about how to get more of what we want at the least amount of cost and risk.

For the most part, we want machines to operate exactly this way. The problem, by Omohundro’s logic, is that we can’t appreciate the obsessive devotion of a computer program to the thing it’s programed to do.

Put simply, robots are utility function junkies.

Even the smallest input that indicates that they’re performing their primary function better, faster, and at greater scale is enough to prompt them to keep doing more of that regardless of virtually every other consideration. That’s fine when you are talking about a simple program like Excel but becomes a problem when AI entities capable of rudimentary logic take over weapons, utilities or other dangerous or valuable assets.

In such situations, better performance will bring more resources and power to fulfill that primary function more fully, faster, and at greater scale. More importantly, these systems don’t worry about costs in terms of relationships, discomfort to others, etc., unless those costs present clear barriers to more primary function. This sort of computer behavior is anti-social, not fully logical, but not entirely illogical either.

Omohundro calls this approximate rationality and argues that it’s a faulty notion of design at the core of much contemporary AI development.

“We show that these systems are likely to behave in anti-social and harmful ways unless they are very carefully designed. Designers will be motivated to create systems that act approximately rationally and rational systems exhibit universal drives towards self-protection, resource acquisition, replication and efficiency. The current computing infrastructure would be vulnerable to unconstrained systems with these drives,” he writes.

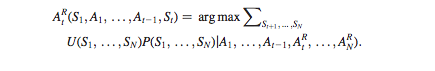

The math that explains why that is Omohundro calls the formula for optimal rational decision making. It speaks to the way that any rational being will make decisions in order to maximize rewards and lowest possible cost. It looks like this:

In the above model, A is an action and S is a stimulus that results from that action. In the case of utility function, action and stimulus form a sort of feedback loop. Actions that produce stimuli consistent with fulfilling the program’s primary goal will result in more of that sort of behavior. That will include gaining more resources to do it.

For a sufficiently complex or empowered system, that decision-making would include not allowing itself to be turned off, take, for example, a robot with the primary goal of playing chess.

“When roboticists are asked by nervous onlookers about safety, a common answer is ‘We can always unplug it!’ But imagine this outcome from the chess robot’s point of view,” writes Omohundro. “A future in which it is unplugged is a future in which it cannot play or win any games of chess. This has very low utility and so expected utility maximisation will cause the creation of the instrumental subgoal of preventing itself from being unplugged. If the system believes the roboticist will persist in trying to unplug it, it will be motivated to develop the subgoal of permanently stopping the roboticist,” he writes.

In other words, the more logical the robot, the more likely it is to fight you to the death.

The problem of an artificial intelligence relentlessly pursuing its own goals to the obvious exclusion of every human consideration is sometimes called runaway AI.

The best solution, he says, is to slow down in our building and designing of AI systems, take a layered approach, similar to the way that ancient builders used wood scaffolds to support arches under construction and only remove the scaffold when the arch is complete.

That approach is not characteristic of the one we are taking today, putting more and more resources and responsibility under the control of increasingly autonomous systems. That’s especially true of the U.S. military, which is looking to deploy larger numbers of lethal autonomous systems, or L.A.Rs into more contested environments. Without better safeguards to prevent these sorts of systems from, one day, acting rationally, we are going to have an increasingly difficult time turning them off.