June 21, 2007, a MQ-4 Predator controlled by the 46th Expeditionary Reconnaissance Squadron stands on the tarmac at Balad Air Base, north of Baghdad, Iraq. AP

Obama To Sell Armed Drones To More Countries

New rules suggest that more drones are headed to the Middle East to fight the Islamic State.

The State Department on Tuesday announced that the United States would be expanding the sale of armed unmanned aerial vehicles, or UAVs, to carefully selected allied countries. The announcement suggests that strategic partners – especially in the Middle East -- could acquire American-made armed drones before the year is out. Some of those could go toward the international campaign against the Islamic State, or ISIS.

Battlefield commanders and the intelligence community are hungry for large, armed drones as they could loiter over targets for hours. The footage captured by high-powered cameras attached to these unmanned aircraft has been critical in determining the locations for airstrikes against Islamic State militants in Iraq and Syria, U.S. officials say.

State Department officials maintained that every export request would meet “a strong presumption of denial,” according to Tuesday’s release, but U.S. officials will allow exports on “’rare occasions’ that are justified in terms of the nonproliferation and export control factors specified in the [Missile Technology Control Regime Guidelines.]”

The Missile Technology Control Regime , or MTCR, is a voluntary partnership that the United States and 33 other countries established in 1987 to curb the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction.

Officials who spoke to the Washington Post said that new export applications would be approved or denied within months of receipt, clearing the way for armed drones and armed drone technology to potentially arrive in other countries by year’s end.

The new policy affects drones that are capable of flying a distance of 300 kilometers and carrying a payload of 500 kilograms. Those specifications come from the MTCR but apply to drones like the Reaper , which are capable of carrying laser-guided bombs and Hellfire missiles.

Exporting more drones--either armed or outfitted with laser targeting systems for smart bombs--to key allies and partners in the Middle East like Jordan would help them strike Islamic State, according to experts.

“Transferring drones, particularly those that had laser designators so they could designate targets for strikes from manned fighter aircraft, to coalition partners such as Jordan participating in strikes against ISIL could be a significant advantage to them,” Paul Scharre, fellow and director of the 20YY Warfare Initiative at the Center for a New American Security, told Defense One.

Earlier this year, a member of the House Armed Services Committee disclosed to the Washington Times that the Obama administration had denied a request from Jordan for unarmed Predator spy drones. But that was before Jordan stepped up its F-16-led air assault to retaliate against Islamic State for the brutal burning alive of First Lt. Moaz al-Kasasbeh, the Jordanian pilot captured by the terrorist group.

“Given our mutual interests, and our strong relationship, it’s absolutely critical that we provide Jordan the support needed to defeat the Islamic State,” Rep. Duncan Hunter, R-Calif., wrote to President Obama in a Feb. 5 letter.

The loosened export rules do not mean that every ally in a pinch will be fast-tracked for the most lethal drones that America produces. Ukraine is reportedly seeking unarmed drones to bolster its campaign against Russian-supported separatists.

“I find it hard to imagine that this would lead to transferring large-scale armed drones to Ukraine, not to mention the fact that they would likely have difficulty operating them effectively. This might help pave the way for transferring small, tactical drones to Ukrainian forces, which wouldn't be a game-changer, but would help them with tactical reconnaissance and would be a sensible move,” said Scharre.

“The new drone export policy is unlikely to lead to the transfer of armed drones to Ukraine,” Michael Horowitz, associate professor of political science at the University of Pennsylvania, told Defense One .

Horowitz and other experts argue that the policy change could allow the U.S. to regain some control if not over armed proliferation at least over how proliferation occurs. Last May, the Chinese Times reported that China would be selling their Wing Loong armed UAV, sometime called a Predator knockoff, to U.S. ally Saudi Arabia.

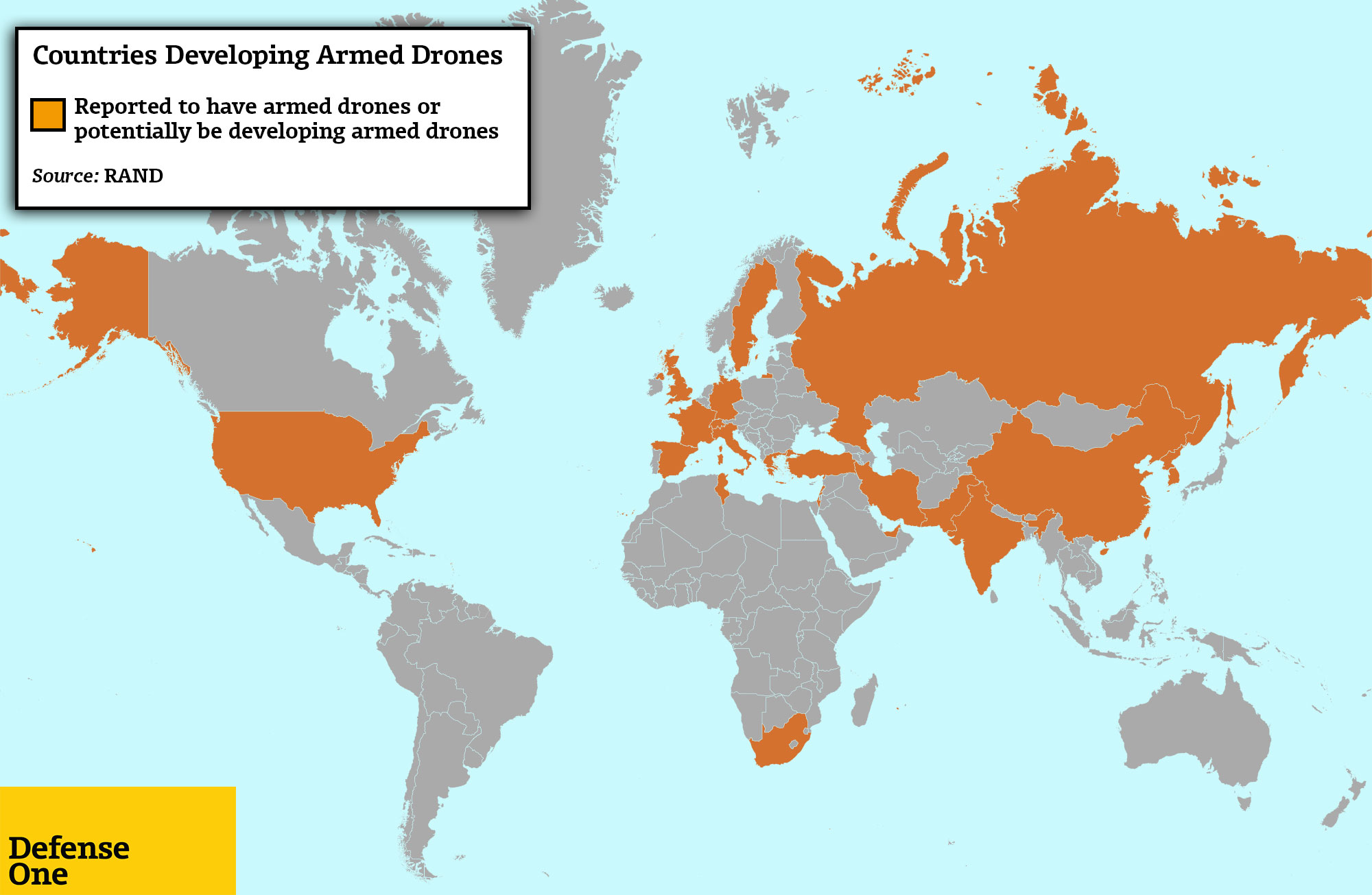

Today, the countries that are confirmed to have armed drones include the U.S., United Kingdom, Israel and China. Experts disagree on whether Iran, Pakistan and Russia have them as well. France and Italy have used unarmed versions of the MQ-9 Reaper drone in places like Mali and have requested armed versions of the same.

The announcement today clears the way for more armed sales to go to U.S. companies. What will that look like?

What the New Rules Mean for US Drone Makers

For years, U.S. defense firms have felt that their international competitors have had a leg up when it comes to selling drones to foreign militaries. Even if an ally had wanted to buy a U.S.-made drone, bureaucratic red tape and other restrictions have slowed or prevented sales.

This loosening of export rules benefits General Atomics, maker of the Predator and Reaper drones, said Roman Schweizer, an aerospace and defense policy analyst with Guggenheim Securities, in a note to investors.

More international sales would also benefit companies that make intelligence and satellite communications equipment for drones, Schweizer said. An uptick in armed drone sales could also benefit Lockheed Martin, which makes the Hellfire missile, the primary weapon on the Reaper.

U.S. allies have been thirsty for U.S. drones, particularly the Predator, Reaper and Global Hawk. Earlier this month, the State Department approved a $340 million sale of four Reapers to the Netherlands. By comparison, two-dozen countries fly the F-16, and the Reaper drone can carry about the same number of weapons as a manned F-16.

“While the new UAV export policy will not, itself, fix the drone pilot gap or other issues particular to U.S. development and deployment of drones, building the capacity of close allies and partners with UAV exports is a functional and helpful way to encourage more interoperability and, over time, potentially help share the burden,” said Horowitz.

“Until now, the U.S. has made it harder for even close allies and partners to buy drones than to buy F-35s or some types of precision-guided munitions. Yet, this did very little to stop the proliferation of drones around the world - it just ensured that the U.S. would have less influence over how countries actually use their drones.”