United States Strategic Command commander Air Force Gen. John Hyten, fourth from right, visits SMDC's Reagan Test Site on Kwaj. U.S. Army Space and Missile Defense Command

The Army’s Space Force Has Doubled in Six Years, and Demand Is Still Going Up

As the service hastens to mint new orbital operators, its leaders are watching the debate over a separate Air Force space corps — and just maybe a new service branch.

The U.S. Army is growing its small force of space operators and enablers, building a Space Cadre of soldiers who understand how to work in space and integrate it into land operations, even as a contentious proposal to reshape the bulk of the U.S. military’s space operations is making its way through Congress.

The Army space force comprises two distinct types of operators: there are the commissioned officers designated for Space Operations, and then there is the Space Cadre, a larger group of uniformed and civilian “space enablers” who spend up to about half of their job working on related issues.

That structure came together about nine years after the 2000 Rumsfeld Space Commission report raised fears about a “space Pearl Harbor” and prompted the Army to start looking at expanding its space force. But in the last few years, there’s been a concerted effort to grow the cadre, said Mike Connolly, who directs the Army Space Personnel Development Office.

“I do think the people sitting here would not have realized just a couple years ago just how quickly it would explode. Because it has now exploded — with the Army Space Training Strategy...introduced in 2013, we get more people interested in it, we have more people talking, ‘Space is now a domain,’” Connolly said.

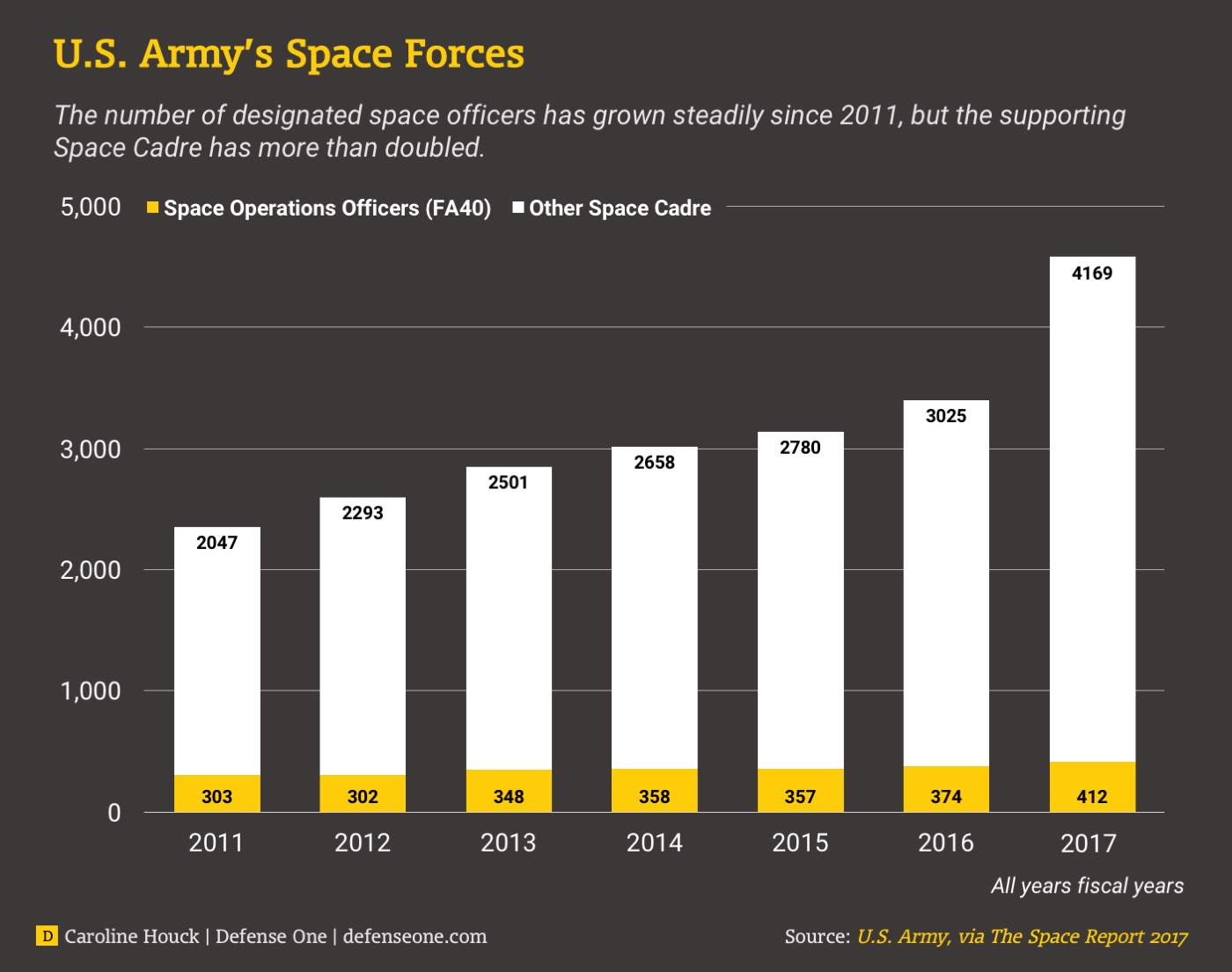

The number of space operations officers — the Army gives them the functional designation of FA40 — has grown steadily, from its original 23 in 1999 to several hundred today. The cadre had been growing steadily as well — then shot up 38 percent over the last fiscal year, according to the Space Foundation’s annual report.

The space force makes up just a small part of the Army; even having doubled since 2011 and including civilians, its 4,500-plus personnel make up less than 1 percent of the total active force. But Robert Hoffman, the Army’s chief of space training, says in a less resource-constrained environment, that wouldn’t be the case.

“We’re on track to train well over a thousand soldiers next year, and we have yet to come close to scratching the itch of what the community is asking for,” said Hoffman, the man responsible for making sure all those individuals gain an understanding of space, tailored to their specialty and rank. “Multiple organizations are requesting, but we simply do not have the resources to provide the course to their locations.”

That’s because more and more soldiers are recognizing the extent to which space capabilities are integrated in day-to-day operations, said Joan Rousseau, who leads the Army’s Space Training and Integration branch.

“Just comparing quarter-to-quarter, from third quarter this year to third quarter last year, we’ve had over a 1,200 percent increase in request for training, and that’s because the word’s getting out that the soldiers are heavily reliant and the Army has become a very space-dependent type of organization,” Rousseau said. “And there’s some recognition of real-world impacts that could affect the commander’s decision cycle and how he deploys his forces.”

Many of the space capabilities the Army relies on aren’t operated by the service, but some are. One recent addition to the Army’s space arsenal: The Kestrel, a small, low-cost, imaging satellite that hitched a ride to the International Space Station on a recent SpaceX launch.

And even if soldiers aren’t immediately aware how much, say, their GPS systems and other critical tools rely on assets in space, it’s fairly easy to open their eyes, Rousseau said: “If I go to a commander and say, ‘Hey, sir, how much of your equipment relies on a space-based capability?’ He may tell me it’s 150, 200 pieces of equipment for his entire brigade. And then the actual unclassified releasable number, we show him a chart that shows him he has well over 2,500 pieces of equipment that rely on a space-based capability.”

The Army may rely on space, but the Air Force is currently the branch that owns it. And some Congressional leaders say that service isn’t doing enough to prioritize the domain.

Rep. Mike Rogers, R-Ala., spearheaded a bipartisan addition to this year’s annual defense bill that would create a new “Space Corps” under the Air Force. Much like the Marines Corps is a separate uniformed service that reports to the civilian leadership of the Navy, the Space Corps would be distinct from the Air Force but report to its secretary.

It’s another idea pulled from the 2000 Rumsfeld report, one that fell by the wayside after the 9/11 attacks led to wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Rogers and his cosponsor, Rep. Jim Cooper, D-Tenn., say the Air Force is shorting space operations of funding and other resources because of its “fighter pilot culture.” (Service officials disagree, vehemently.)

"Space professionals are not managed in a holistic manner within the Air Force,” said Rogers, the chair of the House Armed Services Strategic Forces subcommittee. “There is no formal Air Force space career field outside of space operations and a real cultural problem where rated pilots are prioritized and promoted above space professionals. Only two hours in each of the year-long Air Command and Staff College are dedicated to space, and we can't fill senior billets at Air Force Space and Missiles Systems Center. Protecting, prioritizing and promoting space professionals is best done within a Space Corps."

The Air Force space debate is unlikely to affect the Army in the short term.

"The Space Corps proposal lets the Air Force design the details of the Corps, subject to congressional approval,” said Cooper, Rogers’ Democratic counterpart on Strategic Forces. “Our intention is not to disturb the Army's or Navy's current efforts but to invigorate the Air Force, which has always had the dominant space authority."

But if the space corps proposal passes — it’s not in the Senate version of the defense bill — it could be just an intermediate step to a larger transformation of the entire military’s space operations. Long-term, Rogers envisions the Space Corps maturing into its own separate force, the way the Air Force developed and then split from the U.S. Army Air Forces.

And if that happens, this separate space force might absorb many of the other services’ space operators. For the Army, that could mean fewer FA40 officers — but not necessarily a smaller Space Cadre.

“It is encouraging to see the growth in the Army Space Cadre,” said Micah Walter-Range, who leads research and analysis at the Space Foundation. “Regardless of whether a Space Corps is established, all U.S. military services rely on space and will continue to need personnel who are trained to use space in support of national security.”