A girl walks at a refugee and migrant camp as graffiti is displayed on a wall of a former military base in the village of Moria on the northeastern Greek island of Lesvos on Wednesday, June 17, 2015. Thanassis Stavrakis/AP

The Inequality of War

A new report confirms that more than ever across the globe, peace begets peace and violence more violence. And without significant change, the inequality will only worsen.

There’s a lot of talk these days about inequality of income , less about inequality of war. But such a disparity not only exists but is widening, according to a new report by the Australia-based Institute for Economics & Peace (IEP).

The 2015 Global Peace Index (GPI), which relies on 23 qualitative and quantitative indicators to measure the existence or fear of violence in a given country, includes a number of interesting findings: violent conflicts in 2014 cost the world an estimated $14 trillion (the equivalent of the combined economies of Brazil, Canada, France, Germany, Spain, and the United Kingdom); the number of refugees and internally displaced people (IDPs) is at its highest level since the Second World War; the United States places a middling 94 out of 162 in the report’s ranking of “most peaceful” states.

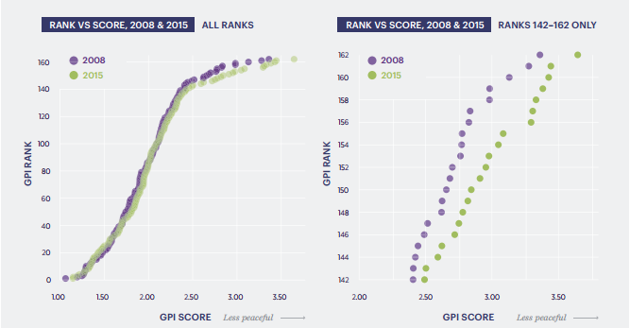

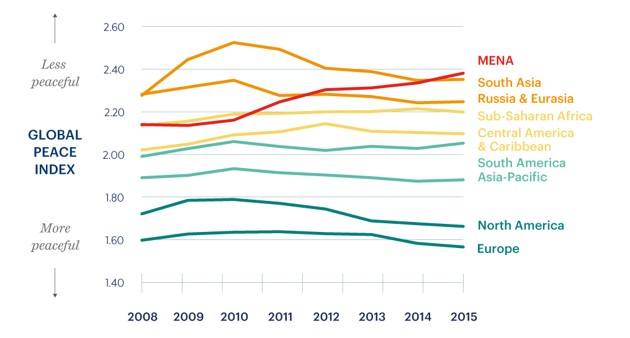

But the clean ranking masks a messier reality. “The least peaceful countries are getting less and less peaceful, and they’re stuck in what appears to be vicious cycles,” Aubrey Fox, IEP’s executive director, told me. The study found that the 20 least peaceful countries have only become less so in recent years. Meanwhile, the most peaceful countries are experiencing increasing levels of peace, revealing “inequality with peace,” according to Steve Killelea, IEP’s chief executive. Killelea “said some countries in Western Europe had now reached ‘quite historic levels of peace,’ enjoying the lowest levels of murder rates and money spent on security ‘probably in the countries’ history,’” the BBC reported .

GPI Rank vs. GPI Score, 2008 and 2015

The greatest changes between the 2008 and 2015 indexes occurred in the 20 least peaceful countries. (IEP / GPI)

Much of this inequality stems from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), the region with the worst score on the index. It’s home to the two lowest-ranked countries, Syria and Iraq, and the country that experienced the greatest decline in peacefulness in 2014, Libya. Among the indicators that have deteriorated the most in the region since 2008 were those related to internal conflict and refugees and IDPs; Syria alone accounted for over a quarter of the world’s IDPs and over 20 percent of its refugees in 2013. The only indicator to improve in the region over that same period—the number of armed-services personnel per 100,000 people (a lower rate is considered good)—had less to do with decreased militarization than with national armies falling apart in the midst of civil wars.

GPI Score by Region, 2008-2015

IEP / GPI

Whereas only three countries occupied the index’s lowest tier of peacefulness in 2008, nine found themselves there this year. Peace inequality also extends to population size: More than 2 billion people live in the 20 least peaceful countries, compared with 500 million in the 20 most peaceful.

“The less peaceful a country is, the more likely it is to experience large swings in peacefulness,” the report’s authors observed. “This is mainly driven by the lack of societal resilience … where shocks to the society can easily result in violent responses. Similarly large increases in peace are possible when countries are ridden by conflict and that conflict then ceases.” By contrast, they added, “Peacefulness is ‘sticky’ amongst countries with high levels of peacefulness.”

In other words, peace begets peace and violence begets violence. And without significant structural changes in the lowest-ranked countries, this form of inequality may only increase.

Last year, IEP published a report with a similar finding about terrorism, noting that 82 percent of deaths from terrorist attacks in 2013 occurred in just five countries : Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Nigeria, and Syria. Steven Pinker, a Harvard psychologist, has also attempted to document violence around the world, and has argued that violence on the whole has actually declined significantly over the past several decades. Last year, he nevertheless acknowledged that the number of war deaths had increased from 2012 to 2013. The culprit behind the uptick? The Syrian civil war.