In this Tuesday, Dec. 11, 2012 file photo, Free Syrian Army fighters look at a Syrian Army jet, not pictured, in Fafeen village, north of Aleppo province, Syria. Manu Brabo/AP

A Who's Who Guide to the Syrian Civil War

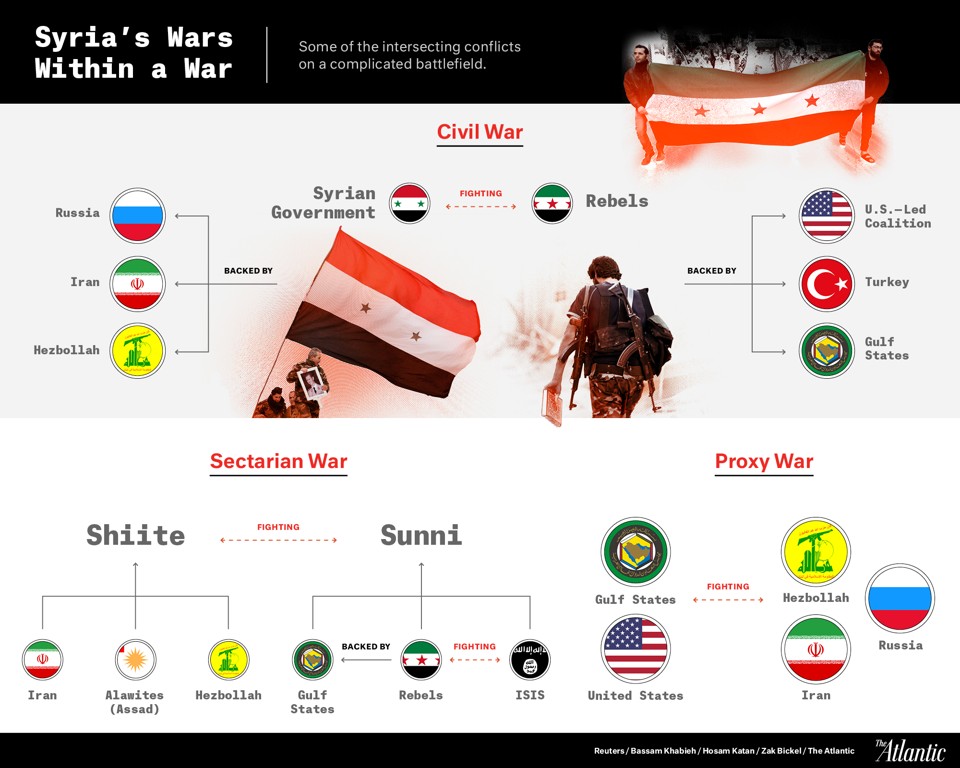

The Syrian war looks different depending on which protagonists you focus on. Here are just a few ways to look at it.

Russia’s bombing campaign in Syria marks a new phase in the Syrian conflict, now in its fifth year. Launched in late September, in response to rebel gains against the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, the strikes were a prelude to a mid-October ground offensive by Syrian government forces to retake territory in the northwest of the country; meanwhile, the United States appears poised to expand its military presence on the ground. Russian President Vladimir Putin may be trying to strengthen Assad’s position ahead of potential political negotiations , brokered by major powers like Russia and the U.S., to end the civil war, writes David Ignatius in an essay for The Atlantic ’s new project, “ What to Do About ISIS? ” But so far, he adds, Russia’s partnership with the Shiite-led governments of Syria and Iran has only deepened the divisions between Sunni and Shiite Muslims that are at the center of the war.

What?

Syria’s conflict has devolved from peaceful protests against the government in 2011 to a violent insurgency that has drawn in numerous other countries. It’s partly a civil war of government against people; partly a religious war pitting Assad’s minority Alawite sect, aligned with Shiite fighters from Iran and Hezbollah in Lebanon, against Sunni rebel groups; and increasingly a proxy war featuring Russia and Iran against the United States and its allies. Whatever it is, it has so far killed 220,000 people, displaced half of the country’s population, and facilitated the rise of ISIS.

While a de-facto international coalition—one that makes informal allies of Assad, the United States, Russia, Iran, Turkey, the Kurds, and others—is focused on defeating ISIS in Syria, the battlefield features numerous other overlapping conflicts. The Syrian war looks different depending on which protagonists you focus on. Here are just a few ways to look at it:

Who?

When we asked readers what they wanted to know about the civil war, one asked: “Who are the various groups fighting in Syria? What countries are involved?” By one count from 2013, 13 “major” rebel groups were operating in Syria; counting smaller ones, the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency puts the number of groups at 1,200. Meanwhile, the number of other countries involved to various degrees has grown; including the United States, nine countries have participated in U.S.-led airstrikes against ISIS in Syria (though Canada’s newly elected prime minister has vowed to end his country’s involvement in the military campaign); Russia is conducting its own bombing against ISIS and other rebel groups, in coordination with ground operations by Iranian and Hezbollah fighters. This is before you tally the dozens of countries whose citizens have traveled to join ISIS and other armed groups in Syria.

Thomas van Linge, the Dutch teenager who has gained renown for his detailed maps of the Syrian conflict, groups the combatants into four broad categories: rebels (from “moderate” to Islamist); loyalists (regime forces and their supporters); Kurdish groups (who aren’t currently seeking to overthrow Assad, but have won autonomy in northeastern Syria, which they have fought ISIS to protect); and finally, foreign powers.

Many of the parties I place in this last category are fighting or claiming to fight ISIS. The divide among them is whether to explicitly aim to keep Assad in power (Russia and Iran), or to maintain that he must go eventually while focusing on the Islamic State at the moment (the U.S.-led coalition).

In that sense, broadly speaking, Russia has intervened on behalf of the loyalists and the United States has intervened on behalf of the rebels, though the U.S. has tried to only help certain rebels, providing arms and training to “vetted” groups. It’s this contradiction in U.S. goals—America wants Assad to go but is also fighting ISIS, one of the strongest anti-Assad forces in Syria, in defiance of “the enemy of my enemy is my friend” principle—that helps answer another reader’s question: “Why is it still so difficult to wrap my own head around our official involvement in the conflict?” Russia’s approach is less sensitive to the differences among rebel groups: It opposes all of them. Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov summed it up at the United Nations earlier in October: “If it looks like a terrorist, acts like a terrorist, and fights like a terrorist, it’s a terrorist, right?”

The Battle for Syria

Airstrike locations are approximate. (Sources: Institute for the Study of War; Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation; U.S. Central Command; Syrian Observatory for Human Rights / Reuters)

Where?

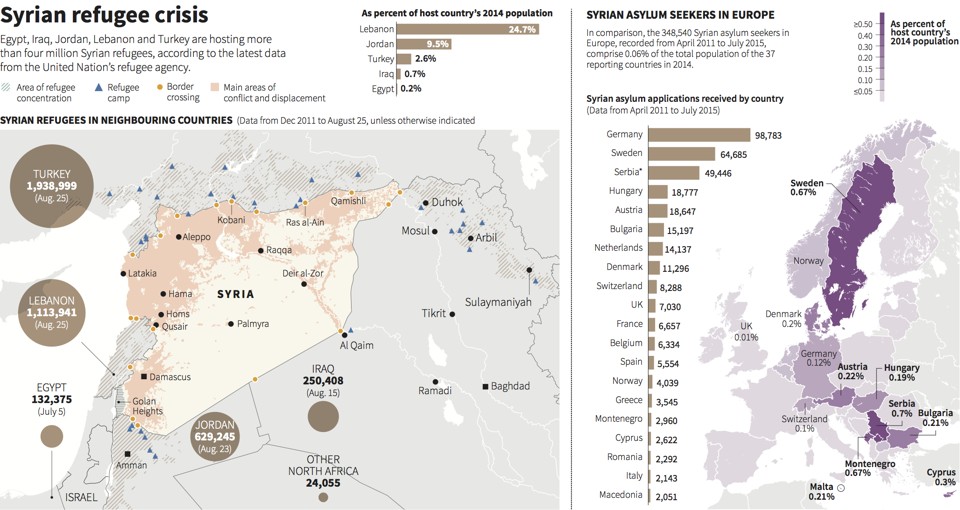

What started in Syria has spread to multiple countries—to Iraq, where ISIS has effectively erased part of the border with Syria and taken over a chunk of the northwest; to Turkey and Lebanon, which together have taken in more than 3 million of the 4 million registered Syrian refugees; to Europe, which has received more than 500,000 asylum applications from Syrians since 2011; and to the United States, which as of this writing has resettled fewer than 2,000 Syrian refugees since 2011 but has pledged to take in 10,000 more over the next year.

(UNHCR; World Bank; Eurostat; U.S. Department of State’s Humanitarian Information Unit / Reuters)

Why?

Why did Syria’s protests of 2011, which began in part as a response to the arrest and mistreatment of a group of young people accused of writing anti-Assad graffiti in the southern city of Deraa, morph into today’s chaos? Or as one reader asked: “What are they fighting about?” The protests started after two Arab dictators, in Tunisia and Egypt, had already stepped down amid pro-democracy demonstrations in their countries. Syria’s war is unique among the Arab Spring uprisings, but it is not unique among civil wars generally. Stanford’s James Fearon has argued that “civil wars often start due to shocks to the relative power of political groups that have strong, pre-existing policy disagreements. … War then follows as an effort to lock in … or forestall the other side’s temporary advantage.” The Syrian uprising presented just such a shock, and the opposition to Assad may have seen a short-term opportunity to press for more gains by taking up arms before their Arab Spring advantage disappeared. An International Crisis Group report from 2011 noted that Assad at first responded to protests by releasing some political prisoners and instructing officials “to pay greater attention to citizen complaints,” but that “the the regime acted as if each ... disturbance was an isolated case requiring a pin-point reaction rather than part of a national crisis that would only deepen short of radical change.”

Once a war starts, an awful logic often keeps it going, according to Fearon: “Given enormous downside risk—wholesale murder by your current enemies—genuine political and military power-sharing as an exit from civil war is rarely seriously attempted and frequently breaks down when it has been attempted.” Another complication: The Atlantic’s Dominic Tierney, among others, has argued that Assad purposely radicalized the opposition to delegitimize the rebellion, by releasing terrorists from prison and avoiding fighting ISIS.

When?

To paraphrase one reader’s question: When does this end? The political-science professor Barbara F. Walter has pointed out that since the end of World War II, civil wars have lasted an average of 10 years, but that the number of factions involved is likely to prolong this one. Ben Connable and Martin Libicki of the Rand Corporation have meanwhile found that insurgencies tend to end when outside state support is withdrawn, and that “inconsistent or partial support to either side generally presages defeat.” With foreign involvement increasing on both sides, neither is likely to win, or lose, anytime soon.

Syria in 60 seconds:

Here’s how Andrew Tabler, an expert on Syria at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, summarized the conflict:

The Syrian Civil War is arguably the worst humanitarian crisis since the Second World War, with over a quarter million killed, roughly the same number wounded or missing, and half of Syria’s 22 million population displaced from their homes. But more than that, Syria today is the largest battlefield and generator of Sunni-Shia sectarianism the world has ever seen, with deep implications for the future boundaries of the Middle East and the spread of terrorism.

What started as an attempt by the regime of President Bashar al-Assad to shoot Syria’s largest uprising into submission has devolved into a regionalized civil war that has partitioned the country into three general areas in which U.S.-designated terrorist organizations are dominant. In Syria’s more diverse west, the Alawite and minority-dominated Assad regime, and a mosaic of Shia militias trained and funded by the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corp (IRGC), hold sway. In the center, Sunni moderate, Islamist, and jihadist groups, such as ISIS and the al-Qaeda affiliate Jabhat al-Nusra, share control. And in the northeast, the Kurdish-based People’s Protection Units (YPG) have united two of three cantons in a bid to expand “Rojava”—Western Kurdistan. As the country has hemorrhaged people, neighboring states have carved out spheres of influence often based on sectarian agendas that tear at the fabric of Syrian society, with Iran (and now Russia) propping up the Assad regime; Turkey, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the U.A.E. supporting the Sunni-dominated opposition; and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) supporting the YPG.