A peshmerga fighter walks through a tunnel made by Islamic State fighters, Tuesday, Oct. 18, 2016. Bram Janssen/AP

The Once and Future Insurgency: How ISIS Will Survive the Loss of Its 'State'

Controlling territory is at the core of the group's ideology, but it isn't everything.

Territory is arguably both ISIS’s greatest strength and its greatest weakness. The land the group seized in Syria and Iraq, which at its peak was thought to be as large as the kingdom of Jordan, enabled the Islamic State to aspire to its grandiose name by declaring a caliphate, drawing recruits from around the globe, and distinguishing itself from the world’s stateless terrorist and insurgent groups.

But that land has also served as a big, fat target for ISIS’s enemies, who have been pummeling the organization from the air and on the ground. By one estimate, ISIS has lost 16 percent of its territory so far in 2016, after losing 14 percent in 2015. It has recently retreated from the Iraqi cities of Ramadi and Fallujah, the Syrian-Turkish border, and the Syrian town of Dabiq, where ISIS members once prophesied a literally apocalyptic battle with infidel armies. This week, a motley crew of forces launched a massive assault on ISIS’s last Iraqi stronghold of Mosul.

Each square mile lost chips away at ISIS’s reason for being. As my colleague Graeme Wood wrote last year, “Caliphates cannot exist as underground movements, because territorial authority is a requirement.” What exactly is the Islamic State, if the “state” all but disappears?

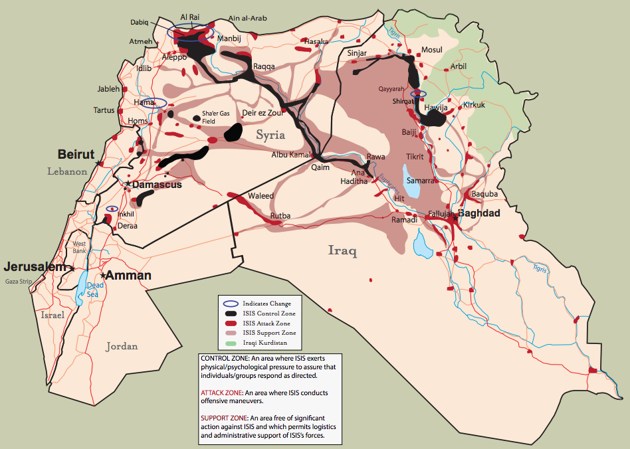

Black indicates territory ISIS controls, dark red indicates territory where ISIS conducts attacks, and light red indicates territory where ISIS enjoys some degree of support. (Institute for the Study of War)

To answer that question, I turned to William McCants, a scholar of Islamic militancy at the Brookings Institution and the author of The ISIS Apocalypse: The History, Strategy, and Doomsday Vision of the Islamic State. We spoke about how territory factored into ISIS’s early ideology, how its leaders have explained their recent setbacks, how the group reconciles its dual goals of building a caliphate and bringing about the end of the world, and how the organization could change in the coming years.

McCants argued that a stateless Islamic State could still carry out terrorist attacks abroad and exploit political dysfunction in Syria and Iraq, even as it struggles to attract foreign fighters and justify its claim to the caliphate. Most of all, I was struck by the timeline he offered for defeating the idea of ISIS as opposed to its physical footprint. The group, he emphasized, accomplished what other jihadist organizations had long dreamt of by controlling substantial territory. “ISIS’s own leaders have said it will take a generation of being denied territory for the effect of that to fade,” he told me. “I think that’s right.”

An edited and condensed transcript of our conversation follows.

Uri Friedman: ISIS came to a lot of people’s attention in June 2014 when it seized Mosul and declared a caliphate. So many people have only known ISIS as a terrorist group that controls significant territory. But ISIS had been around [in various forms] for a decade before it took control of Mosul. How did the organization’s early leaders, including [founder] Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, think about territory and the notion of a physical caliphate?

William McCants: They wanted it. It was Zarqawi who cooked up the scheme to reestablish the caliphate in the area between Mosul and [the Syrian city of] Aleppo. He dreamed it up when he was hiding out in Iran in 2002 after fleeing Afghanistan following the U.S. invasion. He saw the coming U.S. invasion of Iraq as an opportunity to get that land. His plan was to sow a civil war between Sunni and Shiites and then capitalize on it to establish a state. Before his death in 2006 [in a U.S. airstrike], he was already talking about the coming state: “It’s just around the corner, we have formed the nucleus of it.” And when he died, that summer, his successor dissolved al-Qaeda in Iraq and proclaimed it instead the Islamic State of Iraq, even though the group held no territory at the time.

Friedman: How did [Zarqawi’s successor] Abu Ayyub al-Masri justify declaring a new Islamic state with no control over territory?

McCants: With great difficulty. It immediately put the group on the defensive. They said, “Look, you obviously start small, just like the prophet did, and then you go from strength to strength.” It still brought a lot of criticism from the rest of the jihadists because they rightly said: “How can you be a state without land?” So [ISIS has] been in this place before, intellectually—of trying to explain how they’re a state without actually having a state.

They’re going to be in a much more difficult place this time around of explaining how you can have a caliphate without a caliphate, because it’s an even bolder claim than just proclaiming a state within the borders of a contemporary nation-state. They can try to say, “Well, we control territory in other parts of the Muslim world [through the group’s smaller affiliates in countries such as Egypt and Libya] and therefore we’re a caliphate,” but if that territory is also denied to them, what can they say?

Friedman: What is your sense of why Zarqawi emphasized territory so much?

McCants: Because it’s essential if you are going to resurrect the caliphate, which is the early Islamic empire. This isn’t a virtual connection between believers—you already have that, it’s called the ummah. This is meant to be an actual governing structure, and you simply can’t have it without territory.

Friedman: Did Zarqawi have a different sense of immediacy about establishing the caliphate than Osama bin Laden and al-Qaeda leaders did?

McCants: Oh yeah. Most jihadists see the caliphate as something that will be resurrected in the far future, and it will be brought about by Muslim nations coming to terms with one another and forming some larger political unity. Zarqawi saw it in exactly the opposite terms: You establish [the caliphate] as fast as possible, and then you go from strength to strength.

Friedman: How do you think control of territory in Iraq and Syria post-2014 transformed ISIS as a group? How did its theology and ideology change?

McCants: One thing that happened intellectually is that they downplayed in the apocalyptic part of their ideology the coming of the messiah, whereas their early leaders had really played it up and the state was almost incidental. Under [current ISIS leader Abu Bakr] al-Baghdadi they played up the creation, the resurrection of the caliphate as the fulfillment of prophecy. They put their political program on a more stable footing, because messianism is messy. If you get people focused on institution-building and building a state, that’s more durable. This is the same kind of thing that happened in the Middle Ages with other Muslim revolutionary groups with an apocalyptic tinge; they often made the same transition once they began to take and hold territory.

It’s also the case that they got a lot of experience actually running a state. They had to put all this theory into practice, so they learned to govern. Their problem is they didn’t govern well because they were fighting a war on all fronts.

Friedman: Do you think ISIS miscalculated in that sense—that in their efforts to expand territorially they invited a lot of foreign powers to intervene, putting the project at the center of their existence—control of territory—in jeopardy?

McCants: They did. And it’s one of the unresolved tensions in the organization intellectually and programmatically. Here’s an organization that desperately wants to resurrect the caliphate, but they are also seeking to expand it at such a rapid clip that they put the caliphate in dire straits. It would have been one thing if they had taken and held the Sunni Arab hinterland between Syria and Iraq and just sat tight. That’s not what they did. They continued to press outward on all sides, alienating everybody, and therefore putting their nascent empire-building project at risk.

Friedman: Among the group’s leaders, were there tensions about that?

McCants: It would not surprise me, but I have not seen that. I think it is perhaps an unexamined flaw in their political program. They wouldn’t see it as a flaw. They would say, “Look, prophecy has promised that the Muslims will conquer the world. Therefore, because we have resurrected the caliphate, we will inevitably win and losing [the caliphate] is just a setback.” I don’t think that’s just spin that they tell themselves. I think the leadership really believes it. Whether the foot soldiers really believe it is another question.

Friedman: On those foot soldiers: One of the things that attracted foreign fighters to ISIS was the group’s vision of End Times and apocalyptic thinking. So how did ISIS continue to discuss the end of the world in its propaganda and outreach while, as you mentioned, it was deemphasizing that in favor of building the caliphate?

McCants: Two ways. One was presenting the caliphate itself as fulfillment of prophecy, which they did at every turn. The other is that they pointed to important battlegrounds where end-time battles would be waged. They go out of their way to conquer [the Syrian town of] Dabiq in anticipation that prophecy would be fulfilled by a massive infidel invasion. They talk about Constantinople, they talk about Rome—these are the subsequent capitals that are supposed to fall to the Muslim army. They gave up Dabiq [in October] in a hurry, and you could say that therefore they were being cynical about the prophecy—they were just doing this for propaganda. But if it’s just about propaganda, [by] abandoning ship quickly you risk raising a lot of doubts in your followers’ minds. I think it’s probably more accurate to say that they didn’t see that the invading armies were going to come in the numbers the prophecy said they would. They have to have 800,000 infidel soldiers fighting, whereas you had a couple hundred maybe and then a few dozen U.S. military advisors. So they couldn’t plausibly claim that this was the showdown.

Friedman: You don’t see that as 100-percent spin on their part?

McCants: We do not have internal documents to tell us whether these guys are using this cynically or not, so I have tried to remain utterly agnostic on that question and offer both explanations. For the early leadership, we know that they were pretty serious about this stuff based on internal memoranda. I am unsure about the current group of guys. But look, where they have had the opportunity to play their role in prophecy, they have—establishing the caliphate, taking Dabiq, trying to conquer surrounding land. Those are all things in their control and they tried to do it. They can’t control whether their enemies send in 800,000 troops or not.

Friedman: Have you seen ISIS leaders—its ideologues and propagandists—redefining the caliphate as the group loses territory?

McCants: I have not seen that. What I have seen is more of, “Hey, this is a long battle. There will be ups and downs. We may have to go into the desert again. But we’ve been there before and we can make a comeback. Take a look at what we just did, right? This isn’t an empty boast on our part. We made good [on it] and we can do it again.” That’s how they’ve talked about it.

Friedman: On Twitter, you wrote that explaining an unfulfilled prophecy like [the epic battle at] Dabiq is easy compared with explaining a prophecy that was once fulfilled and now might not be, like [the restoration of] the caliphate. Can you elaborate on that?

McCants: They have proclaimed themselves “the return of God’s kingdom on earth.” They have claimed that this is the fulfillment of prophecy. How do they plausibly argue to be the fulfillment of prophecy if their caliphate goes belly-up? I am sort of sickly fascinated to watch what kind of exegetical contortions they put themselves through in order to explain it. To me, ideologically and in terms of propaganda, that’s their greatest vulnerability. The solution to the Dabiq problem is easy: The infidels didn’t show up in the numbers that they were supposed to, so the prophecy didn’t happen. But they have already claimed that this [caliphate] prophecy has been fulfilled.

I anticipate that they will make one of two moves. They will either say, “Well, [the caliphate is] still here because we control little pockets of territory in Syria and Iraq or in other parts of the Muslim world.” Or they may say, “Look, the true caliphate comes and goes and sometimes usurpers are there. What matters is that the institution comes back.” But it’s a question of: Does [the message] continue to resonate [with would-be jihadists around the world] when [ISIS has] been soundly defeated as a government, they’re anemic as an insurgency, and yet they’re still claiming to have returned God’s kingdom on earth? I don’t think it resonates as much.

Friedman: Have we already seen that? [ISIS’s] foreign-fighter numbers are down.

McCants: You could argue it that way, but I’m hesitant to do it [because] there could be other reasons. Europe is tightening up, countries in the Middle East are tightening up, in terms of transit. Turkey is getting more serious about policing its border.

The more [ISIS is] denied territory, the more difficult it is for them to get traction. But they’re going to have to be denied territory for a long time. They are going to benefit for a long time from their success. They did it—what all these other jihadist groups have been talking about for a long time. These guys pulled it off. And it is going to take a long time for the memory of that to fade. ISIS’s own leaders have said it will take a generation of being denied territory for the effect of that to fade. I think that’s right.

Friedman: Looking ahead several months or years, what’s your best guess for what the Islamic State without a physical state, or with anemic territory, looks like? How does the group change in terms of what it does and how it behaves in the world if it doesn’t control Mosul or [its Syrian capital of] Raqqa?

McCants: It continues to have an international terror organization—something they have built as a consequence of having the latitude and freedom to operate in Syria and Iraq. They will also continue to agitate in Syria and Iraq, looking for an opportunity to come back. This is what happened to them before when they were defeated as an insurgency [in 2008-2009]. They didn’t evaporate. They continued to carry spectacular terrorist attacks, assassinate their enemies, and bide their time, because they know that the disgruntlement of the Sunni Arab tribes in Syria and Iraq is going to continue unless there are drastic changes in the way that [the governments in] Damascus and Baghdad behave. Nobody sees that on the horizon, so they have good reason to believe they’re going to get another bite at the apple.

Friedman: So you feel that even if Mosul is retaken and Raqqa is retaken militarily, unless there are political solutions to the Syrian Civil War and to power-sharing between Sunnis and Shiites in Iraq, that the military victories [will be] short-lived.

McCants: No question. And there also has to be a capable security apparatus that is able to bring stability. [ISIS] would not have gained the territory they did in Iraq if it had not been for widespread disenchantment among the Sunni Arabs and the poor performance of the Iraqi military. And those two things are related? [Former Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri] al-Maliki purged a lot of the Sunni officers because he was worried about a coup. He wanted to shore up the Shia nature of the government in Baghdad.

Friedman: Has ISIS, in controlling territory and demonstrating the possibility of a modern caliphate, created a new and dominant model for terrorists organizations? Do you think jihadist groups in the future will view seizing territory as a top priority?

McCants: They will, but it happened before [ISIS’s] takeover [of Syrian and Iraqi territory]. It was al-Qaeda in Iraq and then the Islamic State that put that front and center. And when they were defeated as an insurgency [in 2008-2009], it was other jihadist groups, particularly al-Qaeda affiliates, that took up the program, over the objections of al-Qaeda’s leadership. The real question is: What kind of government [will future jihadist groups try to establish]? And how does one get on with one’s competitors? Al-Qaeda has been experimenting with different models—with Nusra embedding itself in the [Syrian] insurgency, with AQAP in Yemen using a lighter touch in cities that they control, often delegating the authority to local leaders. You could say that ISIS has offered a highly competitive model of how to do this. But it’s not the only one.