An Afghan policeman mans a checkpoint in Wardak province. AP Photo/Anja Niedringhaus

Will Corruption Force U.S. Troops to Abandon Afghanistan?

There’s growing concern that the number of U.S. and NATO troops that remain past 2014 might be too small to oversee billions of aid money to Afghanistan. By Stephanie Gaskell

One of the more popular guessing games in Washington these days is how many U.S. and NATO troops will stay in Afghanistan past the planned 2014 withdrawal to protect the war’s gains. But now there’s growing concern that there won’t be enough of a foreign presence to protect billions of dollars of aid money from being wasted or stolen.

More than $60 billion in international aid has been sent to the Afghan government since 2002. And in 2012, the international community pledged to keep sending about $4 billion a year, on the condition that Afghanistan does more to stop corruption. In the past year or so that Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction John Sopko has been on the job, his office said it has examined more than $10.6 billion in aid projects. “Of that, SIGAR has identified $6.7 billion that we consider to be at risk of waste, fraud and abuse." And now, with coalition troops leaving Afghanistan, there’s even less oversight of many of these reconstruction projects, Sopko said.

In a letter to Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel, Secretary of State John Kerry and U.S. AID director Rajiv Shah, Spoko warned that keeping track of this money “will become prohibitively hazardous or impossible as U.S. military units are withdrawn, coalition bases are closed, and civilian reconstruction offices in the field are closed.”

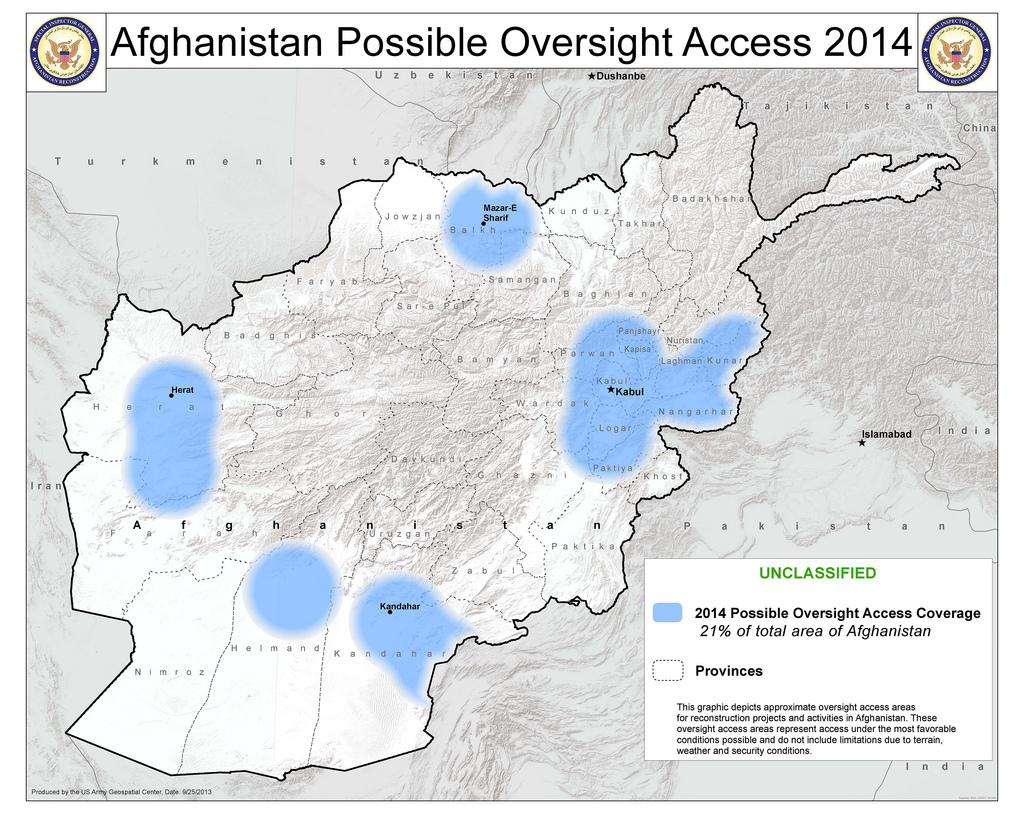

Sopko said that already U.S. military officials have told the inspector general and State Department officials that they will only escort civilian oversight personnel to reconstruction sites that are within a one-hour trip -- the Golden Hour -- of an “advanced medical facility.” That security-based decision, Sopko said, creates ‘oversight bubbles’. The military told the SIGAR that future requests for military escorts beyond that range “will probably be denied.”

[Read more: America's Longest War]

NATO officials have been contemplating leaving as few as 8,000 coalition troops in Afghanistan, just 5,000 of which would be Americans, past 2014. Pentagon Press Secretary George Little said earlier this year that “a range of 8-12,000 troops was discussed as the possible size of the overall NATO mission, not the U.S. contribution.”

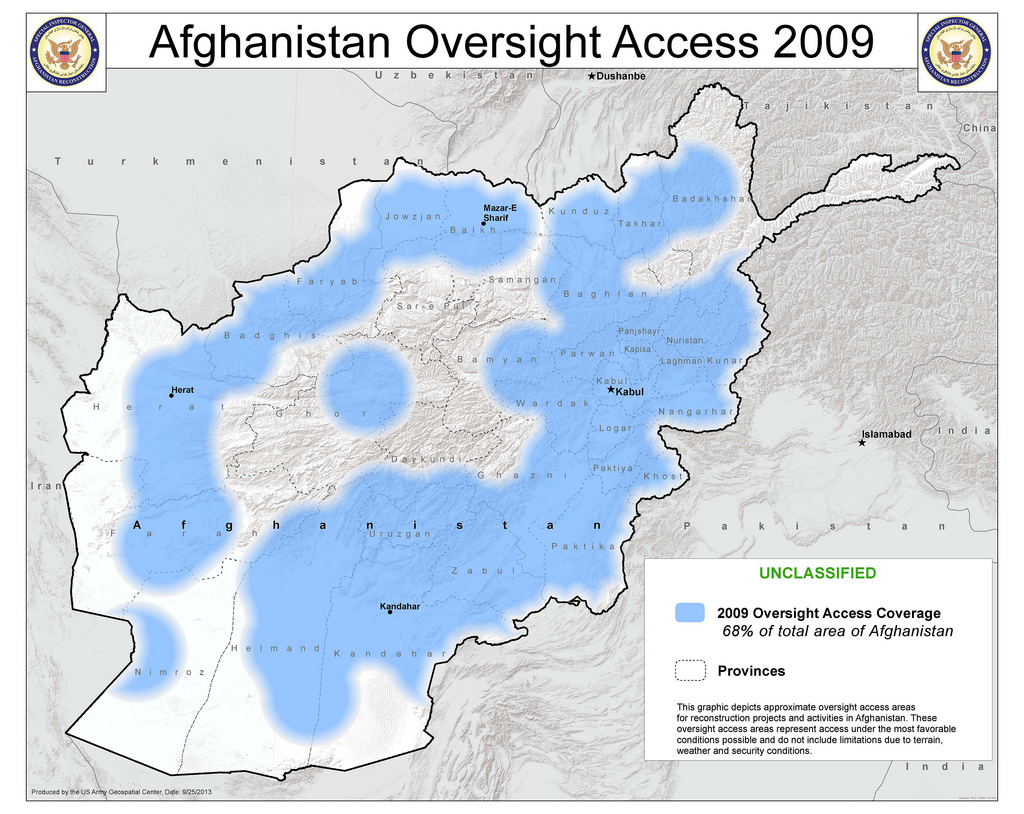

In 2009, at the height of the war, civilian aid workers were able to access nearly 70 percent of the country, Sopko said.

But by 2014, that access could drop to just 21 percent.

The New York Times ’ Thom Shanker reported this week that oversight of aid money was increasingly becoming an issue for NATO countries as they decide on how many troops to leave past the withdrawal. Any post-2014 presence in Afghanistan “is tied directly to the $4.1 billion and our ability to oversee it and account for it,” a senior NATO diplomat told the Times . “You need enough troops to responsibly administer, oversee and account for $4 billion a year of security assistance.”

The aid money was pledged with the condition that President Hamid Karzai, and whoever replaces him in next year’s election, does more to prevent corruption, but little results have been achieved since the 2012 Tokyo summit.

There’s still one more fighting season left before the withdrawal, and military commanders are surely looking to see just how much of a fight the Taliban will put up and whether the Afghan army and police can protect its people. But it’s clear that politicians and diplomats are looking just as closely at whether the billions in aid will be protected too.

On the flip side, Karzai (and his successor) wants that money -- and that could, in the end, be the motivating factor that helps move the needed reform on Afghan corruption and secure an enduring NATO troop presence beyond the official end of the war.