The quest for a universal remote for unmanned systems

QinetiQ NA targets Navy demand for common control of unmanned air and sea systems.

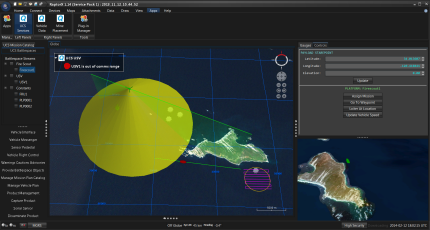

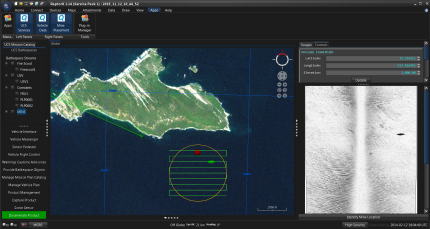

In QinetiQ’s Common Control System, an unmanned sea vehicle conducts mine sweeping while sidescan sonar data is relayed back to the host ship by a nearby UAV.

Unmanned systems continue to proliferate in the United States and abroad as they become more and more capable of providing solutions to a variety of problems. Despite slight budget cuts, the market for unmanned systems remains relatively unscathed.

The past year has demonstrated the continued development of unmanned systems ranging from firefighting robots to autonomous convoys. The capabilities of well-known, battle-tested systems such as the Predator have also increased as enhanced sensor suites and payloads continue to be produced. The UAV market alone is expected to reach $18.7 billion in 2018.

However, increased procurement and R&D of unmanned systems has brought new challenges for the Defense Department and contractors alike.

For instance, the explosion in growth of unmanned ground, air and sea vehicles has also resulted in a command and control problem – each system has its own control software and control stations. As a result, DOD has been trying to standardize the control of UAVs.

“We’ve standardized the means of controlling and communicating between the ground and the bird, and all of the systems involved. The standard that we’re working on is called Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) Control Services, or UCS, and it is hardware independent,” Rich Ernst, who leads the USC architecture development in DOD, told Government Security News.

QinetiQ North America is one of the companies considering the software demand for the standardized control of unmanned systems. As a part of the Future Airborne Capability Environment (FACE) consortium, the company is looking to increase interoperability and software portability for avionics software across DOD aviation. Its solution is the Unmanned Platform Common Control System (CCS).

CCS is software that would be installed on control systems, allowing users to control different types of unmanned systems, ranging from the Navy’s Fire Scout to the TALON explosive ordnance disposal bot. The ultimate goal of the system is to allow a small number of people to control large amounts of assets from just one common console, eventually paving the way for experimenting with different modes of control.

Current common control systems are designed to load the control software for different platforms in parallel – for each different kind of unmanned system, the corresponding software must have been installed into the ground station. In order to avoid inefficiency, CCS seeks to create an architectural layer that will allow translation between one control software suite and any number of unmanned components.

QinetiQ has a history of working with the Navy, which began to focus on the need for common control systems with the development of the Fire Scout and the lessons the service learned from moving the Aegis program to an open architecture. The company has been the sole provider of command and control systems for the Navy’s Tomahawk cruise missiles.

“The Navy didn’t want to have all the different vendors showing up on one ship with their console,” said John Sutton, the company’s executive vice president and general manager. “[The Navy] wants to have a common console, common command and control -- just show up with the platform; we’ll worry about the C2.”

Anticipating a demand for a common control system, QinetiQ decided to internally develop the CCS software based on the company’s previous experience with the Tactical Robot Controller (TRC), a small, wearable device that could control a variety of different unmanned systems.

In speaking with Defense Systems, the QinetiQ NA team noted integration and acquisition challenges in developing the software. Technologically, much of the operations research and R&D already exists for common control systems, and many unmanned systems are similar in terms of architecture.

“We’ve seen the number right now is just under 80 percent commonality in services applied to command and control for each one of those individual platforms across the really small, single manned UAVs to the very large Predator, Pioneer, and UCLASS environment,” said Walt Smith, QinetiQ NA’s senior vice president and defense solutions sector technical director. “And then we’ve taken it one step further -- it’s just about 79.75 percent commonality [of those systems] with the command and control of the TALON robot and the unmanned maritime vehicle.”

A USV moves out of line-of-sight communications from the host ship while the UAV moves into place to relay communications back to the ship.

The primary challenges are thus rooted in integration and acquisitions – the government is still determining what standards will be used for what set of services, hence the need for consortiums such as FACE, which focuses on standards. As program managers and program executive officers acquire more unmanned platforms, the authority and oversight to use a control system will in some cases be directed or undirected in others, Sutton said.

“This is an evolving market from command side and there is not yet a single acquisition view,” he said.

The team also highlighted the challenges related to human cognition. As the number of human controllers decreases and the amount of unmanned assets increase, capabilities are more likely to be limited by human attention span and error. In the future, fewer people will be expected to manage large numbers of unmanned assets.

Mark Hewitt, the company’s executive vice president and chief strategy officer, likens the challenge to a real-time strategy game – both situations feature extremely complex environments with large amounts of data. A good game design funnels important information to the user, providing help in determining the most pressing problems that need to be solved.

In a good game design, an abstraction layer helps reduce the complexity and speed at which things are happening to just those issues that you need to deal with at any given moment, he said. Some of that game technology may be applicable to the common control of large amounts of UAV assets.

Despite these challenges, QinetiQ NA has successfully demonstrated the software to the Navy. One of the demonstrations involved using the software to move a surface combatant into firing positions, while simultaneously controlling a Fire Scout and an unmanned sea vehicle (USV) for minesweeping. The CCS was able to run common services across different platforms – the USV and the Fire Scout were made by two different manufacturers.

The project will be managed by the Navy’s PEO Unmanned Aviation and Strike Weapons and is preparing for an imminent, indefinite delivery/indefinite quantity multiple award contract competition. QinetiQ is planning on another demonstration of CCS before the end of 2014.

NEXT STORY: Navy researchers turn seawater into fuel