How virtual reality helps improve weapons quickly, cheaply

The Army’s SWeET simulation system can display customized scenarios and instantaneously collect ballistics and user-response data.

Small-arms weapon design isn’t easy — significant time and money has to be invested in order to upgrade and modify weapons. A large portion of that investment goes toward testing the new weapons, making sure that they are optimized for performance and usability.

In order to reduce development times, engineers at the Army’s Picatinny Arsenal have turned to simulated, virtual reality testing environments to better gather performance data of weapons, according to an Army release.

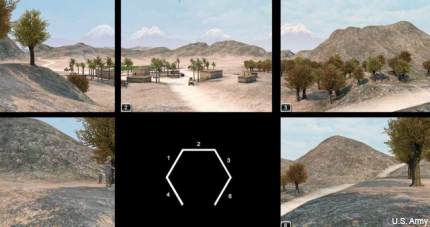

The Simulated Weapon Environment Testbed, or SWeET, uses a combination of ballistics data, cameras and artificial intelligence to simulate weapons testing situations. The system uses five large screens to project a 300-degree view of indoor or outdoor scenarios with customized weather conditions, locations and times of day.

Users — up to four per screen — can be equipped with the M4, M11, M9, M16, M240 and M249. Larger weapons such as the M2 heavy machine gun and the Mk19 grenade machine gun will likely be added in the future. The weapons are almost completely unmodified, except that the bolts and the magazine are swapped out and compressed air is installed to simulate recoil.

A series of cameras are used to capture movements and reactions during testing, while six computers in the back run the scenario and simulate and record realistic projectile ballistics and travel effects.

Programming each scenario can take up to several weeks at a time, but an enormous amount of information such as target distance, reaction time, target response, and user response can be instantaneously collected with each simulation. Also, creating the scenarios is still cheaper than the time and monetary costs associated with manufacturing multiple weapons for the development phase.

"Users can come here and test a weapon or the new ammunition before it is even made," said Clinton Fischer, a mechanical engineer with the Weapons Technology Branch. "In traditional development, they would have to first manufacture the weapon or the ammunition for it — and because there is no production line for it, it could be a thousand dollars a round. Here, we just make it, shoot and get data."

However, SWeET is unable to replicate everything — it is, after all, a simulator.

For instance, the system utilizes two-dimension screens rather than head-mounted displays, meaning that depth perception can sometimes be hard to emulate. Additionally, the compressed air recoil simulation, while relatively safer than other testing systems, is only 90 percent accurate when compared to the real thing.

More sophisticated simulators — for training, especially — have become increasingly popular as military and commercial technology enables more realistic simulations. The military is still figuring them out, however. The Army recently released a solicitation seeking to mitigate simulator sickness in regards to its Dismounted Soldier Training System. Commonly associated with head-mounted simulators, symptoms can include visual impairments and visual-perception flashbacks, which create a false sensation of movement that can last up to 24 hours.