DARPA's Robotics Challenge gets tougher, richer

The teams in the competition are showing a lot of progress, so the research agency has added more difficult tasks—and more prize money—to the upcoming finals.

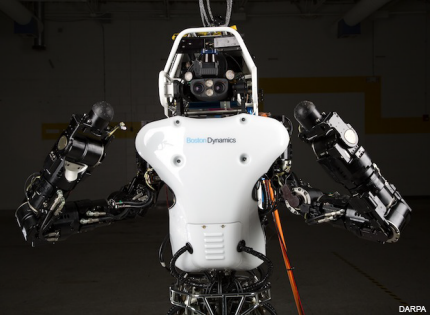

DARPA’s remade and untethered Atlas will take part in the finals.

The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency has upped the ante—in more ways than one—in its Robotics Challenge, a multiyear competition to develop robots that can operate in dangerous environments while responding to manmade or natural disasters.

The finals of the challenge, set for June 5-6 at Fairplex in Pomona, Calif., will feature an expanded field of at least 20 teams, more challenging criteria than in previous events and a bigger pool of prize money. In addition to the $2 million grand prize already announced, DARPA has added a $1 million second-place prize and $500,000 for third.

The research agency said the tougher criteria and extra prize money grew out of progress the teams have made since a semifinals competition held in December 2013.

“During periodic reviews with the DRC [DARPA Robotics Challenge] teams we’re already seeing them perform at a much higher level than they were last year. We’re excited to see how much further they can push the technology,” Gill Pratt, DRC program manager, said in a statement. “As any team will tell you, we’re not making it easy. DARPA has been consulting with our international partners to decide on what steps we need to take to speed the development of disaster-response robots, and the DRC Finals will reflect those realities.”

In the previous event, competing robots had to try to drive a utility vehicle, walk through rough terrain, climb a ladder, clear away debris, open a series of doors, cut through a wall, close a leaking valve and connect a fire hose. Each team was graded on how many of the tasks they could compete.

For the finals, DARPA is adding some additional hurdles, including requiring completely wireless operation via a secure wireless network, without the aid of power cords, fall arrestors or communications tethers. Teams also will not be able to physically help out a robot if it falls or gets stuck; if a robot can’t get itself up, its competition is over. And not only will they have to function wirelessly, but DARPA will degrade communications between the robots and their teams, a situation that would likely occur in a disaster zone. That would force the robots to operate on their own when communications go dead.

One of the competitors in the finals will be DARPA’s own Atlas, which represented a breakthrough of humanoid robotics technology when it was unveiled in July 2013, but had a disadvantage in that it was tethered. For the finals, DARPA and developer Boston Dynamics remade 75 percent of Atlas, keeping only its legs and feet. Lighter materials were used for the rest of its 6-foot-2-inch (and 345-pound) frame, which allowed for the inclusion of a battery and pump system to let it operate untethered.

The DRC features teams from around the world, operating on either funded or unfunded tracks. DARPA provides funding for some teams, as does the European Union and the governments of Japan and South Korea. Some teams also prefer to self-fund, which would give them greater control of their technology. Shortly before the last competition, for example, Google had purchased the Tokyo-based company responsible for Team SCHAFT, which wound up winning that competition. Later, Google moved SCHAFT to the self-funded track, which allowed DARPA to add two more funded teams.