25 teams in finals for DARPA's high-risk Robotics Challenge

The tethers are off and teams from seven countries are ready to throw down in the highly anticipated competition.

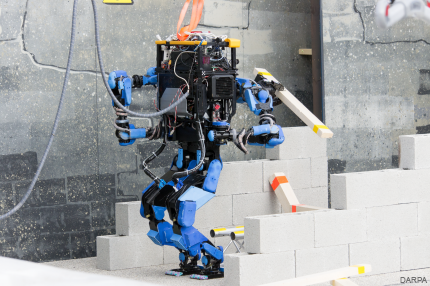

The robot from Team SCHAFT, which scored highest at the DRC Trials.

The field is set for the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency’s Robotics Challenge, which has now grown to 25 teams from seven countries in what has become perhaps the most anticipated—and most difficult—robotics competition ever.

The teams will compete June 5-6 at Fairplex in Pomona, Calif., in a variety of disaster-response tasks, with three cash prizes totaling $3.5 million at stake. But from DARPA’s point of view, a lot more than money is at stake. Although the focus from the start has been on developing robots that could respond to areas too dangerous for humans—inspired by the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear meltdown in Japan—an underlying goal also is to improve the state-of-the-art in robotics.

The international turnout is one positive sign, but so is the progress the teams have made since the DRC Trails in December 2013, progress that has prompted DARPA to make the finals a lot harder than the earlier competition.

In the trials, robots had a tough enough task, operating a vehicle, walking through rough terrain, climbing a ladder, clearing debris, opening a series of doors, cutting through a wall, closing a leaking valve and connecting a fire hose. As in the finals, teams were graded based on how many of the tasks they could complete.

For the finals, DARPA has added some challenging wrinkles. For starters, the robots will have to operate untethered, so teams will have to operate completely wirelessly and on battery power, without the aid of wired communications, fall arresters or power cords. If a robot falls and can’t get up on its own, its competition is over—and considering the difficulty of bipedal robotic movement, that’s a likely end for at least some of the teams. And just to make things more fun, the agency’s competition officials will intentionally degrade communications during the event, forcing robots to employ some autonomous features to operate on their own.

Also, while the finals will contain many of the same tasks as in the trials, DARPA said there will also be a surprise task for those robots that reach the end. One other new twist: rather than competing one at a time on the tasks, the robots will start simultaneously, as if on a single mission, with one hour to finish.

“We’re looking forward to seeing how the teams ensure the robustness of their robots against falls, strategically manage battery power, and build enough partial autonomy into the robots to complete the challenge tasks despite DARPA deliberately degrading the communication links between robots and operators,” DARPA’s DRC Program Manger Gill Pratt said in a statement.

Pratt also said the international flavor of the competition reflects the growing importance of robotics. “The diverse participation indicates not only a general interest in robotics, but also the priority many governments are placing on furthering robotic technology,” he said. “As this technology becomes increasingly global, cooperating with the United States in areas where there is mutual concern, such as disaster response and homeland security, stands to benefit every country involved.”

The competition will feature about 15 different robot forms, with many teams building their own robots and seven adding their software, interfaces and other features to Boston Dynamics’ Atlas, a pioneering robot developed over the years with DARPA and which recently was upgraded to operate without a tether.

The December 2013 trials ended with 11 teams qualified for the finals, all but one of them from the United States. Since then, 14 more have entered from the now seven countries represented, qualifying by submitting a video of their robots completing five of the disaster-response tasks.

The 25 teams taking part, listed by country, are:

Germany

- Team Hector, Technical University of Darmstadt

- Team NimbRo Rescue, University of Bonn

Hong Kong

- Team HKU, University of Hong Kong

Italy

- Team WALK-MAN Italian Institute of Technology, Genoa, and the University of Pisa

Japan

- Team Aero, University of Tokyo

- Team AIST-NEDO, National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology, Tokyo

- Team HRP2-Tokyo, University of Tokyo

- Team NEDO-Hydra, University of Tokyo, Chiba Institute of Technology, Osaka University, Kobe University

- Team NEDO-JSK, University of Tokyo

People’s Republic of China

- Team Intelligent Pioneer, Hefei Institutes of Physical Science, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Changzhou

South Korea

- Team KAIST, Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, Daejeon

- Team ROBOTIS, ROBOTIS, Seoul

- Team SNU, Seoul National University

United States

- Tartan Rescue, Carnegie Mellon University, National Robotics Engineering Center, Pittsburgh

- Team IHMC Robotics, Florida Institute for Human & Machine Cognition, Pensacola, Fla.

- Team MIT, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Mass.

- Team RoboSimian, NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

- Team THOR, University of California, Los Angeles; University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia

- Team TRACLabs, TRACLabs, Inc., Webster, Texas

- Team Trooper, Lockheed Martin Advanced Technology Laboratories, Cherry Hill, N.J., Rensselaer Polytechnic University, Troy, N.Y.; University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia

- Team Valor, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, Va.

- Team ViGIR, TORC Robotics, Blacksburg, Va.; Technische Universität Darmstadt, Germany; Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, Va.; Oregon State University, Corvallis, Ore.

- Team WPI-CMU, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, Worcester, Mass.

- Team DRC-Hubo @ UNLV, University of Nevada, Las Vegas

- Team Grit, Grit Robotics, Grand Junction, Colo.; Colorado Mesa University, Grand Junction, Colo.; AutonomouStuff, Morton, Ill.; Harbrick, Moscow, Idaho.

NEXT STORY: Radar-on-a-chip prototype could guide drones