DOD's cyber evolution, four years later

The department's recently released cyber strategy shows how much the landscape has changed since 2011.

Last week, the Defense Department released a much-needed update its 2011 Strategy for Operating in Cyberspace. The new version, while hitting on many of the same general points—information sharing, bolstering alliances in the cyber realm and protecting DOD infrastructure, to name a few—clearly reflects the evolution and escalation of threats and cyberspace operations over the last four years.

Naming names

One of the most glaring distinctions between the two documents pertains to specific threats. In 2011, DOD’s strategy only spoke in broad terms regarding the threats facing the U.S. in cyberspace, citing “external threat actors, insider threats, supply chain vulnerabilities, and threats to DOD‘s operational ability,” among its concerns. It also mentioned that hackers can gain access to critical civilian infrastructure not associated with military assets.

Conversely, the updated strategy overtly names a litany of state and non-state actors that pose a threat to U.S. while citing specific accounts in which they were culpable. The 2015 DOD cyber strategy names Russia, China, North Korea and Iran as well as ISIS, which uses cyberspace to recruit new fighters and disseminate propaganda, and offers something of a scouting report on them.

“Russian actors are stealthy in their cyber tradecraft and their intentions are sometimes difficult to discern,” the strategy states. “China steals intellectual property (IP) from global businesses to benefit Chinese companies and undercut U.S. competitiveness. While Iran and North Korea have less developed cyber capabilities, they have displayed an overt level of hostile intent towards the United States and U.S. interests in cyberspace.” Also, criminal organizations are generally mentioned as a collective body.

Furthermore, the report notes blurred lines that can occur in cyberspace in which “patriotic entities often act as cyber surrogates for states, and non-state entities can provide cover for state-based operators.” An example of that could be the Syrian Electronic Army, which supports Syrian President Bashar al-Assad but apparently is not part of the government.

Top threat

Another change has been the seriousness of cyber threats. The report soberly points out that from 2013-2015 the Director of National Intelligence identified cyber threats as the number one strategic threat to the United States—a significant statement because it is the first time since Sept. 11, 2001 that terrorism did not top the list.

Playing offense

The 2015 strategy also differs from its previous iteration in that it identifies in more specific terms how the U.S. can respond in to threats in cyberspace. Previously, DOD only held a defensive posture when it came to cybersecurity. DOD since has indicated that it is ready to go on the offensive in the cyber domain against perceived threats.

Sometimes the best defense is a good offense. As such, the DOD and the U.S. government are ready to use offensive capabilities. “If directed by the President or the Secretary of Defense, the U.S. military may conduct cyber operations to counter an imminent or on-going attack against the U.S. homeland or U.S. interests in cyberspace,” the strategy says. DOD could order “cyber operations to disrupt an adversary’s military related networks or infrastructure so that the U.S. military can protect U.S. interests in an area of operations.”

The report also notes that not all cyberattacks will warrant a response in cyberspace. The U.S. could take diplomatic and law enforcement avenues, such as the indictment last year of five Chinese military officials, or the use of sanctions in response to an attack.

Deterrence returns

The trouble with responding is that it can be difficult to attribute attacks to a specific source. So deterrence has gained a new focus in the 2015 strategy, with deterrence tactics and capabilities peppered throughout the 42-page document. The strategy describes a measured three-tiered approach that focuses on effective response capabilities to deter adversaries, effective denial capabilities to prevent attacks from succeeding and strengthening the resilience of networks to withstand attacks.

The only mentions of deterrence in DOD’s 2011 cyber strategy were in reference to collective deterrence that could come from bolstering partnerships with allies and taking steps to prevent insider attacks.

Gathering force

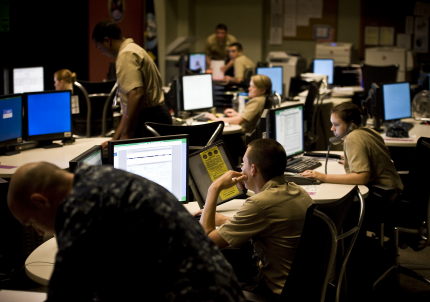

An obvious difference between 2011 and 2015 is the size of DOD’s cyber workforce. The U.S. Cyber Command was established in 2009 as a subcommand of U.S. Strategic Command to focus exclusively on managing cyberspace risk, building partnerships and defensives against cyber threats and ensuring the development of integrated capabilities with related combat commands and through acquisition. The 2011 strategy only went as far as to outline the command structure of Cybercom and identify various training measures the force would implement to ready itself.

The current strategic document gets more specific. For example, in 2012, DOD began to build a Cyber Mission Force (CMF) that will include nearly 6,200 military, civilian and contractor personnel. It expects to fill out that workforce by 2016.

Within the CMF, DOD is constructing 133 teams that, according to the 2015 strategy, will consist of three forces: Cyber Protection Forces, which will defend priority networks and augment traditional defense measures; National Mission Forces that, along with associated support teams, will defend against cyberattacks “of significant consequence;” and Combat Mission Forces, which will support combat commands through integrating cyberspace effects into operation plans and contingency operations.