Fort Knox locks down energy independence

The post could be the Army’s first with the ability to run entirely on its own power.

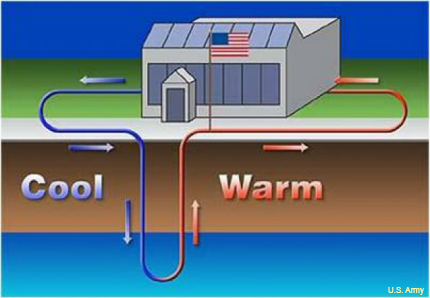

The geothermal process transfers heat from inside a facility to the ground during summer, and extracts heat from the ground during winter.

Fort Knox, for more than 75 years synonymous with gold and a certain kind of green, could soon be known for another kind of green. The installation in Kentucky is set to become the Army’s first post in the continental United States—and perhaps anywhere—with the ability to run entirely on renewable energy.

After more than 20 years of trying—and sometimes failing—to implement energy conservation technologies, officials at Fort Knox are planning to symbolically “pull the plug” on the power grid this spring to signal its capacity to run on geothermal, solar and natural gas power while using that energy efficiently.

"We are now able to provide our own power, heat/gas, water, and wastewater elimination, all from on-post sources without any assistance from the grid if we have to," Fort Knox Director of Public Works Pat Walsh, said in a release.

Energy use is monitored from a control center known as the "bunker."

That puts Fort Knox at the front of the green-energy line for the Army, which has set a goal of using renewable sources for 25 percent of its overall energy use worldwide by 2025. "I am not aware of any other installation, except for possibly Kwajalein Atoll, that can make that claim," Walsh said, referring to the base in the Marshall Islands that is one of the pilot sites for the Army’s Net Zero energy initiative.

Fort Knox has been a pioneer in green energy, with efforts that even predate the Energy Policy Act of 1992, which set a target for federal agencies to improve energy efficiency by 20 percent by 2000. Those efforts have included the kinds of successes and setbacks that tend to accompany pioneering work.

Walsh and his team started with refuse-fired incinerators, but the technology wasn’t advanced enough to make it workable. They then worked with a local power company to install Kentucky’s first wind turbine as a research project, but concluded it was not a long-term solution, the Army said. Solar energy was next, with the team installing what was then thought to be the Army’s largest solar array, consisting of 1.57 megawatts of panels on roofs at the post along with 10,000 panels with 2.1 megawatts across 10 acres.

While the solar-generated power could be connected to the post’s internal grid and supplement electricity needs—and still does—the Kentucky skies can’t be counted on to provide enough sunshine to rely on solar as a primary energy source. So in 1996, the team turned from the skies to the ground. "We have great dirt and rocks in Kentucky," energy manager R.J. Dyrdek, said. "It was then that geothermal heating and cooling became obvious."

The team swapped out aging HVAC systems for geothermal technology, which draws heat from the ground in the winter and pushes it back into the ground during summer. In 2012, Fort Knox received a $1.2 million grant to install a geothermal pond to heat and cools the post’s largest facility. Today, with hundreds of 500-foot wells and nearly 600 miles of underground pipes, the post uses geothermal to heat and cool 6 million square feet across 109,000 acres.

The post’s next step toward energy independence came after a significant step back. The record-breaking blizzard of 2009 brought down trees and power lines, knocking out power to the installation and ceasing all military operations for a week. With its single point of failure exposed, the post set up a “fusion team” to work on alternatives. A key technology also came from the ground—an abundance of methane gas in the layers of shale below the surface.

Heat from generators is captured using a CHP process to heat and cool buildings and provide backup power.

The team began pumping natural gas into buildings on the base and built five electric facilities powered by gas. It also took a geothermal-like approach to the heat generated by the facilities, capturing it in a process known as combined heat and power, or CHP, which is used to heat and cool buildings and provide a backup power source.

Along with developing alternative energy sources, Fort Knox also has put a lot of emphasis on more efficient use. It installed onsite generators to handle power from the local utility, giving it control over the commercial power used, a move that has cut its reliance on the utility by 50 percent, saving $8 million a year. More than 50 buildings at the post have Energy Star certification, indicating their energy use is at least 30 percent less than federal requirements. It monitors energy use from a control center known as “the bunker,” has switched to LED light bulbs and has worked to educate post workers and tenants, as well as the surrounding community, on energy efficiency.

Fort Knox will mark its accomplishments at an upcoming public event, but Walsh and his team aren’t done. They’re considering improvements for the next five years and beyond, which they said could include more solar arrays, configuring government vehicles to run on compressed natural gas and replacing the remaining HVAC systems.

"There is always more we can do as technologies change, and technology change is occurring ever more frequently," Walsh said. "Some of our early energy-efficient lighting projects in the mid-90s have long ago paid themselves off and are now dinosaurs compared to modern lighting technology. I think it is almost time to look backward to go forward."