Army addressing an emerging threat: drones as IEDs

The service has adapted missile defense technology to defend against small drones that could pose a threat to friendly forces or infrastructure.

The C-RAM anti-missile system is being adapted for use against small UAVs.

stringent export policies

There have been some close calls recently, such hobbyist drones crashing on the grounds of the White House, forcing many to call for greater and more robust methods of detecting these small aircraft, which literally fly under the radar used to detect larger craft. But even detecting a weaponized small hobby drone, such as the device with radioactive material that landed on the Japanese prime minister’s residence, might not do any good, unless they can also be neutralized.

With that point in mind, the Army has creatively adapted a program designed to counter rockets, artillery and mortars, a process they call C-RAM, for defense against small UAVs, according to an Army news release.

The Army sees this as a way to address an growing threat. "Every country has [drones] now, whether they are armed or not or what level of performance,” said Manfredi Luciano, the project officer for the Extended Area Protection and Survivability Integrated Demonstration, which encompasses the C-RAM program. “This is a huge threat [that] has been coming up on everybody. It has kind of almost sneaked up on people, and it's almost more important than the counter-RAM threat."

According to Nancy Elliot, a spokeswoman with the U.S. Army's Fires Center of Excellence at Fort Sill, Okla., the range of unmanned aircraft systems has grown from about 20 system types and 800 aircraft in 1999 to more than 200 system types and approximately 10,000 unmanned aircraft in 2010.

In both military and civilian contexts, the range and variance of these systems engenders a lot of options for malicious intent. “In addition, due to their size, construction material, and flight altitude, hobbyist drones are difficult to defend against if their presence in a particular area is unknown or unexpected,” Kelley Sayler, associate fellow at the Center for a New American Security, wrote in a recent paper. “These factors could in turn increase the likelihood that hobbyist drones – particularly those assembled by the operator, and thus not subject to manufacturer-installed geofencing – could be weaponized and autonomously deployed in a terrorist attack against civilians or in an IED-like capacity against patrolling military personnel.”

That’s a concern for the military, particulalrly in asymmetric conflicts—IEDs buried in the ground caused as many as two-thirds of U.S. casualties suffered in Iraq and Afghanistan. “Drones will enable airborne IEDs that can actively seek out U.S. forces, rather than passively lying in wait,” Sayler wrote. “Indeed, low-cost drones may lead to a paradigm shift in ground warfare for the United States, ending more than a half-century of air dominance in which U.S. ground forces have not had to fear attacks from the air. Airborne IEDs could similarly be used in a terrorist attack against civilians or in precision strikes against high-profile individuals or landmarks.”

That’s why the Army is adapting C-RAM for use against UAVs. "The smaller and smaller the protective area, the more efficient the gun systems become compared to missiles," Luciano said. "You don't need as many, and the gun system has certain logistics advantages."

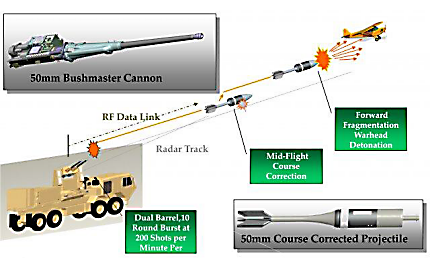

The EAPS ARDEC gun alternative could include a 50mm cannon to launch command guided interceptors and use a precision tracking radar interferometer as a sensor, a fire control computer and a radio frequency transmitter and receiver for launching munitions into an engagement basket, the Army said.

In April, the development team tested the system by shooting down a class 2 UAV – a short range tactical UAV such as the RQ-7A/B Shadow 200 – with command guidance and command warhead detonation.

"In order to minimize the electronics on board the interceptor and to make it cheaper, all the 'smarts' are basically done on the ground station," Luciano said. "The computations are done on the ground, and the radio frequency sends the information up to the round."

The system tracks incoming threats and interceptors, then computes the best trajectory correction for the interceptor as to maximize mission success. According to the release, the ground station uplinks the maneuver and detonation commands, while receiving downlinked assessment data.

The next stage will see more scenario-based testing in which engineers might attempt to intercept and destroy UAVs under a more complicated scenario.