An unmanned U.S. Predator drone flies over Kandahar Air Field, southern Afghanistan, on a moon-lit night, Jan. 31, 2010. Kirsty Wigglesworth/AP

What Drone-Strike Data from Yemen and Pakistan Says about the ISIS Fight

Washington's drone program has cost a great deal of blood and money with little to show for it. Absent a political strategy, the effort in Syria will likely fare no better.

This week, the Washington Post published a story about a new U.S. plan to use lethal drone strikes in Syria to destroy ISIL capabilities on the ground.

The desire to do something—anything—to destroy the capabilities of a group so luridly destructive is understandable, but our haste to show results will likely result in a hollow victory at best.

Proponents of lethal drone strikes argue they are an effective way of reducing operational capabilities and that they make Americans safer .

Critics of the program argue that the risk of civilian casualties is too high and constitutes a human rights violation . They add that the secondary effect of radicalizing bystanders outweighs any tactical successes.

I offer an additional, simpler critique, based on 14 years of experience analyzing and working with programs designed to reduce conflict, insurgency and violent extremism worldwide: there’s no evidence that drone strikes work.

On the contrary, ample evidence shows drone strikes have not made Americans safer or reduced the overall level of terrorist capability. The strikes amount to little more than a waste of life, political capital and resources.

The numbers on drones

There are two countries with a sustained history of lethal U.S. drone strikes to draw on for data: Yemen and Pakistan.

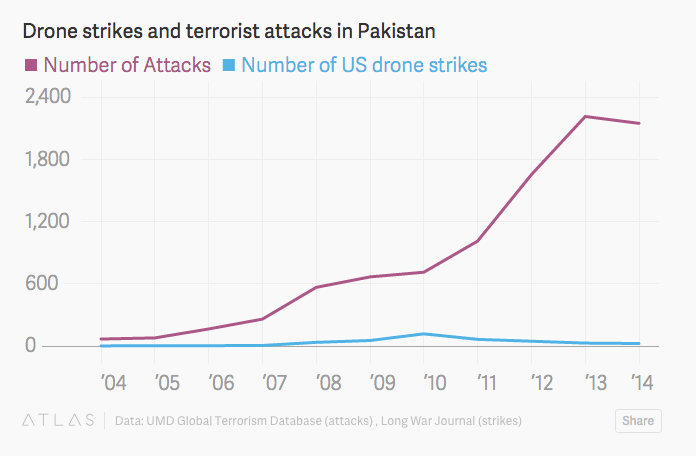

Drone strikes in Yemen began with a single missile fired in 2002, paused for several years and then resumed in 2009. Strikes began in Pakistan in 2004. I looked at the University of Maryland’s Global Terrorism Database for numbers and trends of attacks in both Yemen and Pakistan, and in The Long War Journal for numbers of drone strikes.

The bad news starts immediately. Pakistan made the top ten list for highest number of terrorist attacks worldwide during the first year of strikes. Yemen made the list in 2010, a year after they restarted. Both countries have stayed on that list ever since.

With the exception of a slight decrease in Pakistan in 2014, the number of terrorist attacks against American targets within both Yemen and Pakistan went up, not down, since drone strikes began.

Domestic think tanks like the RAND Corporation and even conservative research centers like the staunchly pro-drone Heritage Foundation report that the number of threats against the U.S. has also increased over the past few years. There hasn’t been a successful attack on U.S. soil for some time, true. But the credit for that goes to efforts that blocked plans from being carried out, not to drones that were supposed to stop the plans from getting created in the first place.

In Yemen, not only did overall numbers of attacks increase each year, but the number of attacks by the al-Qaeda affiliates the U.S. primarily targets kept increasing as well .

If we take a narrow enough view in Pakistan, it can look like there are successes. Attacks by al-Qaeda are almost nonexistent in Pakistan these days, but the overall number of attacks by all actors has increased—focusing on one group alone is obviously asking the wrong question.

Despite the assertion by Georgetown’s foreign affairs expert Daniel Byman that the senior leaders killed by drones are not easily replaced, the number of “number two al-Qaeda leaders” killed since 2001 is so high that even the satirical publication The Onion started making fun of it as a metric back in 2006. CNN’s announcement of “top leader” Nasir al-Wuhayshi’s assassination in Yemen this past June reported his death and his replacement’s name in the same article.

Why airstrikes won’t do it

The impossibility of winning a war through airstrikes alone is taken as fact within the military.

During my own time in the infantry, our drill sergeants considered it a truism that “the infantry will never be out of a job because you can bomb all you want, but someone still has to go root them out and sit on it.”

Unless the United States is willing to put a large number of its own boots on the ground to back up the airstrikes and hold the territory, those troops would need to be local. Where would the US find local troops?

In Syria, the only forces available belong to Bashir al-Assad, a despot seemingly intent on using them to eradicate his own population. The US-supported militias in Syria are far smaller than the US expected for its investment and performing vastly worse than was hoped for .

Iraq does have the military capability, but we are choosing not to launch this new drone program there.

In both Syria and Iraq, we face an even more fundamental problem. Lacking a cohesive, articulate political strategy for governance and post-ISIL reconstruction, no military solution can produce the results we’re looking for. Sean Naylor reported in Foreign Policy this June that ISIL is recruiting more new members than we kill.

We have a slight advantage in that unlike the cellular, decentralized al-Qaeda, ISIL has carved out territory that it holds and intends to keep. This provides a stationary target on which to drop the proverbial hammer, but ISIL is drawing in fighters in great numbers from around the world. Without blocking that “supply side,” killing leadership within ISIL-controlled areas alone makes little sense—that isn’t where the replacements are coming from.

Civilian casualties of US drone strikes have decreased over time, largely by making a shift and carrying out strikes only away from populated centers. The nature of al-Qaeda targets allowed us to do that, but ISIL’s command and control is located in urban areas, where the idea of “surgical strikes” is pure fiction. Although the targeting systems on our missiles are extremely precise, the blast radius ( between 15-20 meters for Hellfire missiles) is not.

Nowhere could I find a way of crunching the numbers so the drone strikes worked. The program thus far has resulted in a great deal of blood and money spent with nothing to show for it. Lacking the political strategy, more of the same in Syria promises no better.

This post originally appeared at The Conversation .