President Barack Obama and Vice President Joe Biden shake hands with the troops following the President's remarks at Fort Campbell, Ky., May 6, 2011. (Official White House Photo by Pete Souza)

Obama Punts Controversial War Account to Successor

The president, who decried the Pentagon’s 'dishonest' war chest, will leave office with it firmly entrenched.

The fate of the Pentagon’s war chest will be left up to a successor of President Barack Obama, who tried to rein in Defense Department spending but wound up expanding the use of a budget accounting gimmick in an era of fiscal turmoil.

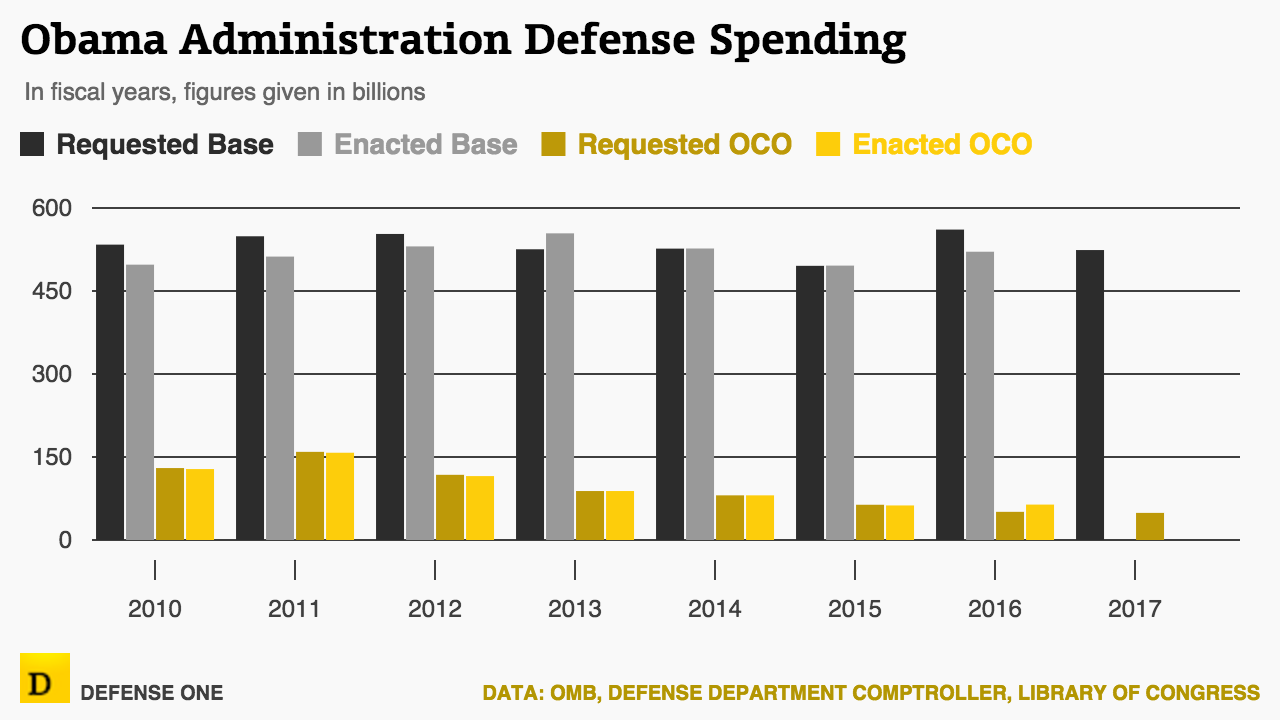

The Pentagon’s war budget — formally called the overseas contingency operations account, or OCO, and formerly known as the supplemental request — is being used far more broadly than it was when when Obama entered White House seven years ago. Today, it helps pay not only for the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, but for combat operations in all regions of the world, training in the United States, and new equipment for the military.

“This [war] budget provides us everything we need, we believe, right now to execute our global operations,” Deputy Defense Secretary Robert Work said at the Pentagon Tuesday when he unveiled the Pentagon’s fiscal 2017 budget request of $583 billion, including a $59 billion war budget.

In his first presidential campaign, Obama said he wanted to end the use of supplemental budgets for the military. After he took office, there was a strong push inside the Office of Management and Budget, the arm of the White House that oversees the federal budget, to tighten the criteria for war spending. And after just a month on the job, Obama criticized the Bush administration’s use of what was then called the Global War on Terror supplemental spending request.

“For too long, our budget has not told the whole truth about how precious tax dollars are spent,” Obama said in February 2009. “Large sums have been left off the books, including the true cost of fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan. And that kind of dishonest accounting is not how you run your family budgets at home; it's not how your government should run its budgets, either.”

A few months later, then-Defense Secretary Robert Gates took the first steps in moving war-funded items, especially soldier support programs, back into the Pentagon’s base budget.

“We must move away from ad hoc funding of long-term commitments,” Gates said that April. “Thus we have added money to each of these areas and all will be permanently and properly carried in the base budget.”

Then-Secretary of Defense Robert Gates speaks to Marines at Forward Operating Base Cafferata, Afghanistan, on March 9, 2010. (DoD photo by Cherie Cullen)

The effort started with some promise as war-born task forces were realigned or eliminated. Money for projects like the Air Force’s drone program were shifted and the process of institutionalization started to take hold. But just a few years later, the defense budget would get turned on its head. Unable to strike a long-term fiscal deal with Republicans, Congress capped the Pentagon budget in the Budget Control Act of 2011. By March 2013, automatic spending cuts, known as sequestration, hit the Pentagon’s base budget, reducing troop training and arms purchasing. This left the uncapped war budget as a spending loophole to fund all sorts of military projects, including home station training and operations outside Afghanistan. And it has been the Pentagon’s relief valve ever since.

“[I]n the OCO budget as submitted we have funded all of our anticipated operational costs, both in South Asia as well as across the North and West Africa portions of our trans-regional fight against terrorism and the violent extremist organizations,” Air Force Gen. Paul Selva, vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said Tuesday. “That has all been fully covered.”

While Congress has at times criticized the Pentagon’s use the war budget as a loophole, they also have used the caps to circumvent spending caps. Last year, lawmakers moved $5 billion from the base budget to the OCO account.

“We have money that is in OCO that should be in base,” Work said. “It just happened over the last 14 years of war. And we have to address that.”

Mike McCord, the Pentagon comptroller, justified the account, saying Tuesday the Obama administration has brought greater predictability to the war budget request.

“We moved from what was the practice of the previous administration was to submit one or two supplementals to building a good-faith estimate of what the wars were going to cost into the budget [and] submitting it with the [base] budget,” McCord said. “I think that we've had, as a result, pretty decent predictability and certainly greater transparency than what came before.”

But others don’t buy the Pentagon’s justifications and criticize Obama and Congress for expanding the use of the war budget.

“OCO has been abused for years to pay for items that have nothing to do with fighting wars,” said William Hartung with the Center for International Policy. “Adding more to an already inflated OCO request would mean throwing what little budget discipline that is left at the Pentagon out the window.”

But what to do differently is anyone’s guess and with Pentagon spending capped through 2021, the floating war chest is likely to remain intact.

“Is OCO going to become permanent? If it’s not, then you’ve got a major issue of what to do with several tens of billions of dollars of funding for troops and equipment that probably need to stay there at least for the foreseeable future,” said Robert Hale, the former Pentagon comptroller for Obama’s first six defense budgets, now a fellow at Booz Allen Hamilton.

With major combat operations complete in Iraq and Afghanistan, some inside the administration have argued throughout Obama’s presidency that all of the war money should be moved into the base budget.

“But what do you do?” Hale said. “Without relief from the Budget Control Act you just really don’t have the room to bring it back into the budget.”

Hale predicts the war chest will “limp along or better yet” the next administration “redefines” the budget account to broaden what OCO can fund.

Supporters of the war budget say it has been the only way to properly fund the military as global threats have skyrocketed. These threats have prompted the administration to dramatically shift its spending priorities since January 2012, a time when the Obama administration was looking beyond the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, envisioning a pivot to the Asia-Pacific region to counter China’s military build-up.

Just as spending priorities were shifting to buy weapons for a war with China, Russia invaded Ukraine and the Islamic State, a little-known militant group, captured large swaths of Iraq and Syria. Iran has continued to cause unrest in the Middle East and North Korea has been trying to build nuclear weapons, most recently testing a long-range rocket this weekend.

In addition to paying for continued operations in Afghanistan ($41.7 billion) and the military’s latest campaign against Islamic State militants ($7.5 billion), Obama’s latest budget sets aside $3.2 billion to pre-position position Army equipment in Europe, part of Pentagon initiative to deter Russia.

Hale called the fiscal situation “some of the worst budget turmoil that I’ve ever seen in 40-or-so years of working with the defense budget.” But, he argued the Obama administration and Pentagon he served haven’t done such a bad job considering those challenges.

In the past five years, Congress has not passed the budget on time, civilian workers have been furloughed twice through sequestration and a government shutdown.

“In light of budget chaos, I think the budget has evolved in ways,” he said. “It’s met a least minimum needs and I think the department should feel good that it has at least managed to do that.”

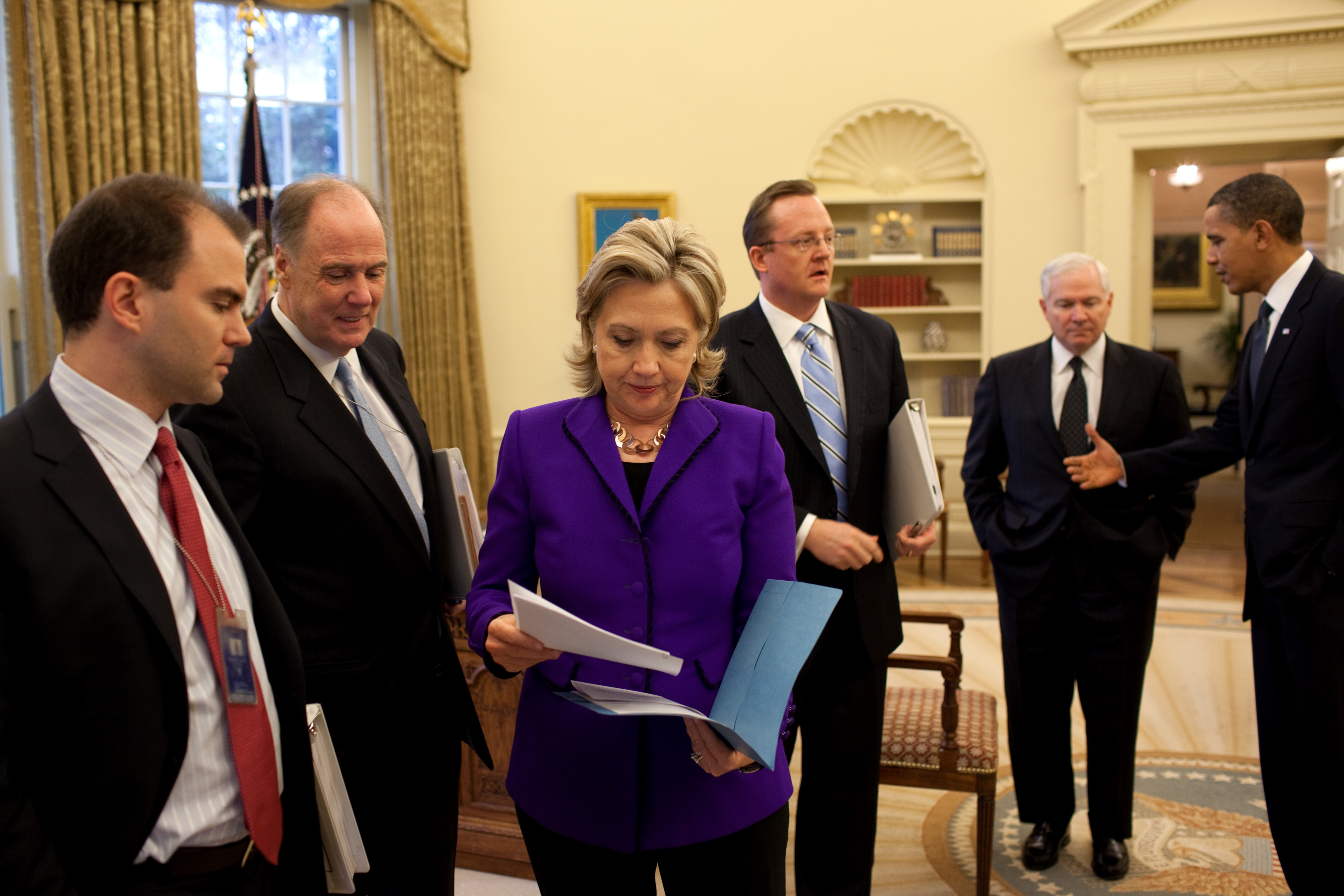

Secretary of State Hillary Clinton confers with Deputy National Security Advisor for Strategic Communications Ben Rhodes, and Deputy National Security Advisor Tom Donilon, as President Barack Obama talks with Press Secretary Robert Gibbs, and Secretary of Defense Robert Gates in the Oval Office, prior to the announcement of the New START Treaty, March 26, 2010. (Official White House Photo by Pete Souza)

Hale touted “business reforms” and so-called efficiency drills to eliminate waste, started by Gates and continued by his three successors, to reduce defense spending.

“Some of those yielded some substantial money,” Hale said. “The administration can feel good that it did this for [the Pentagon] in the midst of two wars in a very difficult period of budgetary turmoil.”

But the Obama was unable to push through any big reforms to military compensation, healthcare, and base closures that it has championed over the past five years. Despite that, Hale championed Gates for killing low-priority or under performing projects in 2009, Obama’s first budget proposal.

“[Gates] made a lot of courageous decisions,” Hale said. “Many of those he made personally and made work personally.”

And they’ve been the only ones to stick.