Brazil's President Dilma Rousseff attends the Paris Agreement on climate change ceremony, Friday, April 22, 2016 at U.N. headquarters. Mary Altaffer/AP

Is it a coup or isn’t it? Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff claims the impeachment proceedings against her, which have now progressed from the lower house of Congress to the upper house, have “no legal foundation” and “all the features of a coup.” Vice President Michel Temer, who would succeed Rousseff if the Senate votes to remove her from office, says the process is constitutional and not a coup at all.

“I’m very worried about the president’s intention to say that Brazil is some minor republic where coups are carried out,” Temer recently told The New York Times . Crying coup has consequences when you’re leading one of the largest economies and democracies in the world.

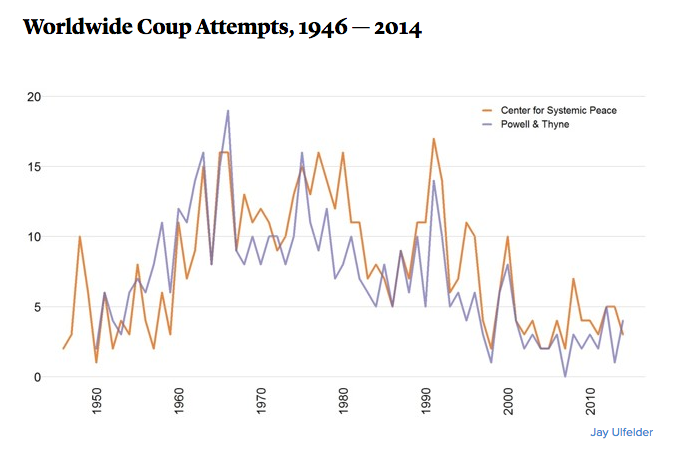

But these days, straight-up coups are rarely carried out in any republic, minor or major. According to data gathered from 1950 through 2015 by the political scientists Jonathan Powell and Clayton Thyne, there have been no more than three successful coups per year in the 21st century. In the 1960s, that number got as high as 12.

Last year, the political scientist Jay Ulfelder combined two datasets, that of Powell and Thyne and another by the Center for Systemic Peace , to plot the number of coup attempts around the world over time. There is no one definition of a “coup,” but Ulfelder described the type of incident that qualified for inclusion in the chart below as “a forceful seizure of national political authority by military or political insiders.”

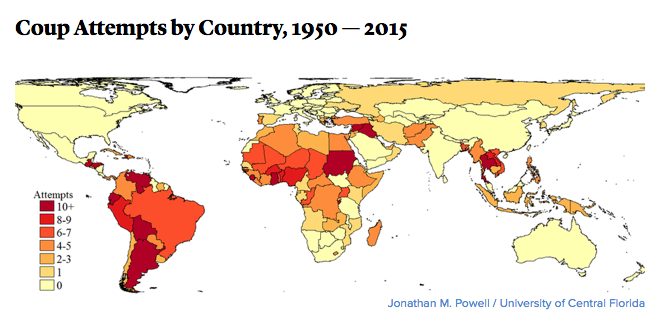

These attempts have been concentrated in Africa and Latin America, which accounted for 37 percent and 32 percent, respectively, of total global coups tracked by Powell and Thyne through 2010.

There are several theories for why the number of coups has been declining since the 1990s. When the Cold War ended, the U.S. and U.S.S.R. stopped supporting coups in each other’s satellite states, and democracy came to be widely recognized as the sole form of legitimate government. In this new climate, those who interrupted the democratic process frequently found themselves pariahs. Globalization has also made illegal seizures of power costly, since those takeovers, and the instability and uncertainty surrounding them, tend to invite international sanctions, deter foreign investment, and inhibit domestic economic growth. (This may be, in part, why Brazil’s vice president wants to tamp down the president’s coup talk.)

It’s obviously good news that coups are a fading phenomenon. But one troubling byproduct of these trends is that they’ve produced profound confusion over how to classify political upheavals that appear to honor the letter of the law, but not the spirit—what you might call dubious democracy.

Making sense of such developments is particularly difficult in relatively young democracies whose institutions are still fragile and taking form (Brazil transitioned from dictatorship to democracy in 1985). It’s even more difficult when the majority of the public—including, often, a rising middle class intent on restoring political stability and economic growth—backs the dubiously democratic process (roughly 60 percent of Brazilians support Rousseff’s impeachment, though many would prefer that she and the vice president resign, making way for early elections). And it’s more difficult still when much of that public, and their political leaders, are haunted by the ghosts of coups past (between a 1930 coup and 1985, Brazil enjoyed only two decades of democratic governance).

Many Brazilians have no memory of their country’s military coups—the dictatorship ended 31 years ago, and half the country’s population is under the age of 30—but many do. Rousseff herself was imprisoned and tortured for opposing the military regime that seized power in a 1964 coup . Her ghosts are real.

In numerous ways, the events of 2016 have little in common with those of 1964. Rousseff is accused of a genuine violation of the law : hiding a government budget deficit with loans from state banks during her 2014 reelection campaign. An independent judiciary has permitted the impeachment vote in Congress to proceed. That vote is now working its way through Congress as stipulated by the Constitution . Coups are typically abrupt, but the current process is moving with all the speed of a sloth (by the time Rio hosts the Olympics in August, Rousseff could conceivably be suspended but not yet permanently removed from office). No force has been deployed; the military is not an actor in this drama. The lawmakers casting ballots against Rousseff are channeling the will of most Brazilians, who want her out of power not just for her alleged budgetary shenanigans, but also for driving a once-booming economy into recession and failing to address corruption within her party and governing coalition. Graft and irresponsible governance are afflicting the body politic, and its immune system seems to be responding properly. This, in essence, is the argument of those in the not-a-coup camp.

But those in the other camp argue that even if Rousseff engaged in more-than-creative accounting—tactics other elected officials have previously employed—that doesn’t amount to an impeachable offense under the Constitution. And it especially doesn’t amount to one when you consider that 60 percent of the 594 members of Brazil’s Congress are themselves facing or under investigation for arguably more serious charges like bribery, money laundering, and electoral fraud. Many of the lawmakers who have so far voted for impeachment, including the speaker of the house, who is leading the campaign against the president, have been implicated in a multibillion-dollar corruption scandal involving the state oil company Petrobras. Some say that even if the impeachment isn’t a coup, it’s a cover-up by politicians hoping to distract from and declaw investigations into their own wrongdoing.

Rousseff, moreover, is a leftist leader whose socialist policies are popular among poor and working-class Brazilians; many of her opponents are right-leaning politicians whose base includes members of the business community and the middle and upper classes. A souring economy has aggravated tensions between these segments of society, and a polarized press has amplified those tensions. In broad strokes, these poisonous dynamics were also present during the 1964 coup . What’s changed, the president and her supporters claim , is that the conspirators have traded in their uniforms for suits, their tanks for crumpled copies of the Constitution.

Writing in The Washington Post on the looming “soft coup” in Brazil, the Latin America expert Héctor Perla Jr. asserted that right-wing parties across the region have in recent years sought “to tarnish left-wing politicians in power through institutional, as well as non-electoral and undemocratic means.” As an example, he cited the hurried, two-day congressional impeachment in 2012 of Paraguayan President Fernando Lugo for “poor performance” in office—a process ostensibly prompted by a deadly clash between police and landless farmers.

But instead of interpreting the impeachment proceedings in Brazil and Paraguay as representative of shapeshifting 21st-century coups, perhaps it’s more productive to discard the coup terminology altogether, particularly in a region where the term is so redolent of real, traumatic ruptures with democracy. The impeachment vote in Brazil “is analogous to jurors ruling against a defendant based not on the charges, but because they think she is a bad person,” the political scientist Amy Erica Smith wrote in a response to Perla in the Post. “This does not constitute a coup, but it is a misuse of democratic procedures.”

This is dubious democracy, an old problem with new urgency in Brazil and elsewhere. And recognizing it as such could generate useful reforms. In Brazil, those concerned with what’s transpiring could advocate for more stringent due-process guarantees for a president facing impeachment. (Why, for instance, were lawmakers allowed to reveal their position on impeachment in the media before the lower house held its vote?) Or Brazilians could seek to address the flaws in a presidential system with so many political parties that it functions like a parliamentary system—except without the capacity to hold a vote of no confidence in the prime minister when the relationship between the executive and legislature malfunctions, leaving the country’s leaders unable to govern and heightening the risk of political violence.

Indeed, the political scientist John Polga-Hecimovich has argued that impeachment is a presidential system’s crude equivalent of a no-confidence vote. “[I]impeachment serves as an escape valve for democracy that allows presidents to fall and democracy to endure,” he writes. “[T]he military stays in the barracks and the regime bends but does not break.” The key question in Rousseff’s impeachment is whether Brazilian democracy is bending too easily, not whether it is broken.

Likewise, international organizations like the South American trade bloc Mercosur, which issue rulings on which countries are abiding by democracy and which aren’t, could articulate in greater detail how they arrive at their sometimes-perplexing decisions. Rousseff has suggested that she might lobby Mercosur to suspend Brazil for not adhering to the bloc’s “democracy clause”—a clause that spurred Mercosur to temporarily suspend Paraguay after Lugo’s impeachment, only for the organization to then admit Hugo Chávez’s Venezuela even though Venezuela too suffered from democratic deficiencies, just of a different sort .

If the impeachment of Dilma Rousseff shouldn’t be called a coup, that’s not because all is well in Brasília or because the description makes Brazil seem like some minor republic. It’s because “coup” doesn’t capture what’s ailing the Federative Republic of Brazil.

NEXT STORY: Leave Root Causes Aside—Destroy the ISIS ‘State’