In this Sunday July 3, 2016, file photo, an Iraqi man looks for victims at the site of a deadly truck bomb attack in a commercial area of the Karada neighborhood, Baghdad, Iraq. Hadi Mizban/AP

Is Global Terrorism Getting Worse? Depends on Your Definition

Civil war is driving many recent attacks, and that blurs both statistics and remedies.

These days, terrorism seems not just more lethal and more common, but more widespread. The death toll in recent weeks speaks for itself: 22 people dead in Bangladesh, 49 gone in the United States, 44 gone in Turkey, 292 gone in Iraq, then another 37, another 12, yet another 12.

And by one oft-cited measure—the Institute for Economics and Peace’s Global Terrorism Index—that’s true. As a rough representation of the global threat of terrorism nearly 15 years after the 9/11 attacks—nearly 15 years after George W. Bush declared that his “war on terror” would “not end until every terrorist group of global reach has been found, stopped, and defeated”—the findings are extremely disheartening. War, they suggest, has only brought more terror.

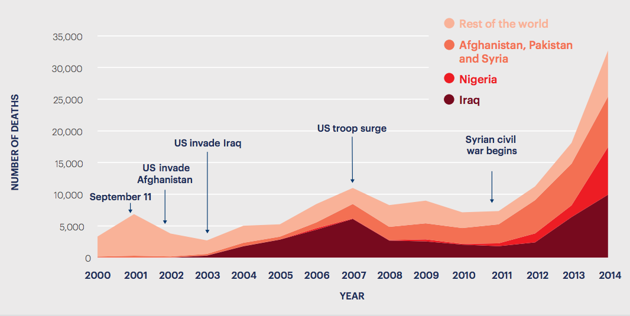

Deaths From Terrorism, 2000 — 2014

Global Terrorism Database / Institute for Economics and Peace

In 2015, terrorist attacks occurred in almost 100 countries—up from 59 in 2013—according to the University of Maryland’s Global Terrorism Database, which the Institute for Economics and Peace relies on for its analysis. ISIS, for its part, appears increasingly to be training its sights on overseas targets as it loses territory in Iraq and Syria.

Fear has spread as well. In June, the Pew Research Center reported that ISIS was viewed as the top threat in eight of 10 European countries that it surveyed, edging out other dangers like climate change and global economic instability. Around the same time, CNN polling revealed that Americans were more likely to expect terrorist attacks in the United States in the near future than at any point since March 2003, shortly after the U.S. went to war in Iraq.

But why is that? Why, 15 years after Bush vowed to defeat terrorism, does it seem like the world is awash in it? According to Daniel Byman, a terrorism expert at Georgetown University, one of the key explanations boils down to two words: civil war. Byman argues that the severity of the terrorist threat depends on where you look.

It’s worth noting that the graph above has its flaws. Collecting data on terrorist attacks is difficult and subjective. (How, to begin with, do you define “terrorism”?) The chart is from the most recent Global Terrorism Index, which does not include statistics from 2015 and 2016. More recent data indicates that the total number of deaths from terrorist attacks actually decreased slightly between 2014 and 2015, with fewer fatalities in Iraq, Pakistan, and Nigeria.

Nevertheless, terrorism is in fact “significantly worse in the Middle East” than it was several years ago, before the rise of ISIS, Byman told me. “Europe has a serious problem, though it’s had serious problems in the past” with terrorist attacks in Madrid and London, for example. “And the United States has a problem, but in context with past terrorist attempts”—excluding 9/11, which “was off the charts”—“this is in line with that. ... The attacks that have happened [have been carried out by] lone wolves who are dangerous. But that’s actually less dangerous than trained infiltrators like we saw [during the 2015 attacks] in Paris.” Between 2000 and 2014, less than 3 percent of deaths from terrorism occurred in Western countries, according to the Institute for Economics and Peace.

Donald Trump asks why they hate us—why jihadists have it out for Americans. But the data shows that terrorism today is not about us, at least not primarily. Though they may profess hatred of Westerners, terrorists are largely tormenting conflict zones like Iraq, Afghanistan, and Syria.

Civil wars like the ones in these countries are particularly potent breeding grounds for terrorist groups, Byman has argued—and this is one reason terrorism has gotten so bad in the greater Middle East.

In explaining why this happens, Byman compared terrorism to robbery. You can think about robbery in terms of grievances: “Why do people steal? Because they’re poor and they want something.” Or you can think about it in terms of capability: “Why do they do it? Because they can. … You and I might steal, if there was no penalty—if we could walk into a jewelry store and take stuff and there were no cops.”

Civil wars increase both grievances and capability, Byman said. They produce vicious cycles of grievances—“you could be displaced from your home, your brother could be shot.” And they produce capability by gutting government authority. If 40 people tried to overthrow the U.S. government, he said, they might kill some people, but they’d also be arrested. But if the U.S. government isn’t functioning because the country’s gripped by civil war, those same 40 people can overtake a town and swell their ranks. “Wars in general create opportunities for groups, and at the same time create grievances that groups feed on,” Byman noted.

Which is why one of the signature features of the “war on terror”—the invasion of Iraq—ended up unleashing more terrorism. “When a stable government is destabilized and collapses, that’s very bad from a counterterrorism point of view,” said Byman. This is true with or without massive U.S. involvement, as Syria’s civil war demonstrates.

Both civil wars offer muddled lessons for how a future President Trump or Clinton should design U.S. counterterrorism policy, according to Byman. He suggested an approach not unlike that which Barack Obama has pursued: “I end up with: Bad things are going to happen, and what we need is some degree of offensive [military] capability to keep the bad guys off balance, we need aggressive global cooperation to go after the global web [of terrorists], we need some homeland defenses, and we need … domestic resilience because some attacks will happen. I look at [the attack in] San Bernardino in particular and say, ‘I don’t know what really could have been done [to prevent] that one, with all the benefit of hindsight.’”

Still, Byman noted, Americans may perceive terrorism as an acute threat because the 9/11 attacks primed them to view most security issues through the lens of terrorism, whether or not it makes sense to do so. He pointed out that during the Vietnam War, the Viet Cong’s terrorist tactics were generally interpreted as elements of revolutionary or guerrilla warfare, not terrorism. And Europe and the United States experienced far more terrorist attacks in the 1970s and 80s than they do now, though most of these were less deadly than today’s suicide bombings.

“Once you discover something that seems new, all of a sudden it’s everywhere,” Byman said. On September 12, 2001, Americans looked at the world anew.

And yet focusing on terrorism blurs other parts of the picture. Yes, ISIS practices terrorism, but it also governs territory, devoting much of its budget and personnel to maintaining an army and police force, minting money, establishing law and order, offering some semblance of social services, and so on. Saying ISIS is a terrorist organization is “like saying the Department of Defense is a health-care organization,” Byman told me. “It is. It’s the largest health-care bureaucracy in the U.S. government. But oh, by the way, they do something else.”

The recent car bombing in Baghdad, for example, represented something in between terrorist tactics used in conventional war (ISIS sending suicide bombers to kill enemy forces) and clear-cut terrorism executed outside a war zone (the Paris attacks). The bombing was “clearly directed against civilians, it’s clearly terrorism, but part of the purpose is to advance the Islamic State in a war, to demoralize the Iraqi military and police,” Byman said.

In several countries in the Middle East, he said, people have good reason to feel gravely threatened by terrorism. But elsewhere in the world, it’s more that people are paying greater attention to the terrorist threat than they used to. “We’re labeling things ‘terrorism,’ where before it would have been seen in the context of civil wars,” Byman argued. “It screws up our basic understanding of the most important question, which is: Are things getting worse?”