Afghan youths overlooking Kabul on Tuesday, April 1, 2014. Muhammed Muheisen/AP

The Newfound Political Power of Afghan Youth

Afghanistan's historic election is a contest not just of candidates but of generations. By Uri Friedman

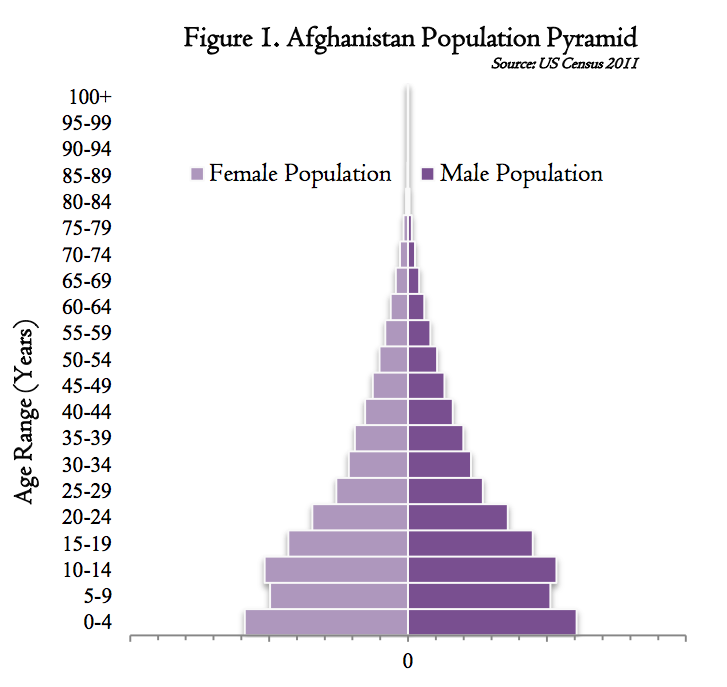

On Saturday, amid the cold and rain, an estimated 7 million Afghans headed to the polls to choose from a roster of presidential candidates whose average age is 63. This in a country where 68 percent of the population is under the age of 25—where seven in 10 people were 12 or younger when the U.S. invaded Afghanistan.Arguably the most important storyline in this weekend's election—which marks the first democratic transfer of power in Afghanistan's modern history—is the participation of Afghan youth, who will play an outsize role in shaping the country's future as U.S. troops withdraw. Ahead of this year's poll, Afghan election officials predicted that the majority of voters would be young people (the voting age is 18), which explains why presidential frontrunners like Ashraf Ghani and Zalmay Rassoul pledged to carve out more than half the positions in their government for the younger generation—and why the race has produced initiatives like a contest to develop a hip-hop anthem for the election.

But in Afghanistan, campaign promises and rap songs aren't enough to court the youth vote—the challenges in engaging young people go well beyond apathy about the political process. The men jockeying to replace longtime President Hamid Karzai are an unappealing, all-too-familiar mix of warlords and government insiders. And in recent weeks, the Taliban repeatedly vowed to violently disrupt the election, in part by reprising a 2009 tactic of attacking people with blue ink on their finger—a measure to prevent voter fraud that also makes it easier for the militant group to target voters.

What's remarkable is that many young people have treated these obstacles as an opportunity to get more involved in the election, not less. On Monday, representatives of the Kabul-based Young Activist Network for Reform and Change (YARC), an umbrella organization of social and civil-society groups that includes some 300,000 members, inked their fingers a week ahead of the vote to encourage Afghans to participate in the election despite the Taliban's threats.

"Even if the Taliban and al-Qaeda cut off my hand or finger, as a youth, I will still take part in the elections," YARC member Sangar Amirzaizada

told

Afghanistan's Tolo News. (This year,

The New York Times

reports, voters are getting invisible ultraviolet ink on one finger and blue silver-nitrate ink on another, meaning people "in troubled areas could be identified by insurgents for some three days.")

"Even if the Taliban and al-Qaeda cut off my hand or finger, as a youth, I will still take part in the elections," YARC member Sangar Amirzaizada

told

Afghanistan's Tolo News. (This year,

The New York Times

reports, voters are getting invisible ultraviolet ink on one finger and blue silver-nitrate ink on another, meaning people "in troubled areas could be identified by insurgents for some three days.")

The younger generation's emergence as a powerful political force has gone beyond symbolic actions. The National Democratic Institute notes that they are the reason campaigning via social media and mobile technology have, for the first time in Afghan electoral history, become critical components of the race (in 2013 there were 2.4 million Internet users in the country, up from 2,000 during the 2004 election). In March, Afghanistan's election commission reported that young people constituted a staggering 70 percent of provincial council candidates across the country (YARC itself has put forward more than 35 candidates for provincial councils).

And these young people appear to be more concerned with building the country's future than litigating its past, which has been dominated by warlords, ethnic conflicts, and civil wars. "Our elders are divided, but the youth are more united," the youth activist Israr Karimzai told Stars and Stripes. "There are certain candidates that are playing the ethnic card in this election, but Afghans have been through the process of national solidarity and they are aware of national interest."

Ehsanullah Hikmat, the head of YARC's international-relations committee, expressed similar views when we spoke on Friday, just hours before the election. He explained that the organization, which has not endorsed a presidential candidate, cares most about the contenders' policies for young people, women, and Afghans as a whole—not factors like the candidates' ages or what side they were on in the country's civil wars.

"About 1.5 million Afghan youth are unemployed. What are the schemes for this unemployment?" he asked. "What are the schemes for the economics of our country?"

"We need peace. We need stability. We need infrastructure. We need schools, roads, hospitals," added Hikmat, a 25-year-old from Logar province who studied diplomatic relations at Kabul University. He said that while young people in cities like Kabul and Herat are especially focused on economic issues, their counterparts in rural areas are more worried about security. He wants Afghanistan to sign a pending Bilateral Security Agreement with the United States, and he's opposed to the so-called "zero option" that the Obama administration is considering, in which no U.S. troops would remain in the country by the end of 2014.

But, as Hikmat's comments suggest, Afghanistan's younger generation isn't a monolith. And not everyone in his age cohort is embracing democratic values.

Earlier this month, Borhan Osman, a political analyst in Afghanistan, wrote that less educated young people in rural areas tend to be "politically inactive," while a growing number of more educated young people in conservative urban areas are flocking to Islamist groups that oppose democracy and elections and favor sharia-based forms of governance:

In many cases, scepticism towards elections stems from experiences in the post-Taleban democracy era, which was riddled with war, corruption, manipulation, political exclusion and the rule of warlords and patronage politics. Dissatisfaction with the government seems to have tarnished the reputation of all democratic politics that produced the government, driving people to seek alternatives they perceive as ‘better’. In conservative segments of society, religious groups have often offered as an alternative the form of an Islamic state based on sharia law. This discourse pits an ‘Islamic’ system against a democratic system – in the marred form Afghans experienced during the past decade. In Khost, for example, in many discussions with young people, from school teachers to madrassa tutors and university graduates, the dominant discourse was that elections were un-Islamic because they have come from the West and are not based on Islamic principles of governance. Digging deeper in conversation, however, the author understood that opposition to election was based more on grievances with the politics of the past decade than an authentic and detailed religious argument. These young Afghans appeared more supportive of the Taleban than of the government, recalling grievances they and their communities had with the government and Western forces in recent years, for example, night raids and the killing and detention of villagers. The Taleban themselves have never been supportive of an electoral system – and have not spelled out or developed their general ideas about the country’s future political system, apart from vaguely seeking ‘an Islamic state’.

These findings hint at one of the key questions in this weekend's historic election. As the United States leaves Afghanistan, what lessons will young Afghans—the country's future leaders—draw from the last decade and a half of war and instability? Will they work to improve Afghan democracy and elect more effective and accountable leaders, or will they spurn the democratic process in favor of a system they perceive as superior?