Former President George W. Bush speaks in front of Congress during the 2002 State of the Union Address, on January 22, 2002. Doug Mills/AP

How America's National Security Hawks Empowered Iran

Invading Iraq didn't strengthen America's hand with Tehran. In fact, it did just the opposite. By Conor Friedersdorf

The Associated Press reported on Monday that Iraqis now consider Iran a more important ally against Sunni extremists from the Islamic State than the United States, and that as a result, "Tehran's influence in Iraq, already high since U.S. forces left at the end of 2011, has grown to an unprecedented level." The story quotes an Iraqi official who reports that Iran sold Iraq $10 billion worth of weapons over the last year. Says Iraqi lawmaker Mohammed al-Karbuly, "Iran now dominates Iraq."

This is an important moment to revisit some recent history.

Roughly 13 years ago, President George W. Bush declared Iraq, Iran, and North Korea to be members of an "axis of evil" (though Iran and Iraq were enemies at the time). Prominent Bush administration officials believed that the invasion and occupation of Iraq would strengthen America's hand in relations with Iran. Undersecretary of State John Bolton told Israel prior to the Iraq War that the U.S. would deal with Iran after the conflict was over. And assumptions implicit in that fantasy plan would soon emerge as conventional wisdom in the mainstream media.

For example, on April 11, 2003, 60 Minutes aired the dispatch, " Iran: The Country Next Door ," which began, "When Saddam developed a nuclear bomb, we responded with total war. How do we respond if Iran does the same? Morley Safer reports from Iran." The ensuing analysis leaned heavily on Geoffrey Kemp, then the director of regional strategic programs at the Nixon Center. He is paraphrased as arguing that "Iran will feel dangerously isolated after the U.S. war with Iraq is over," and stated the following in his own words: "We will be not only a major presence in Iraq. We will be in Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Oman. We're all around them, and we're encircling them with the most extraordinary military power the world has ever seen assembled. They are very nervous about this."

Around the same time, Josh Marshall was writing about another hawkish argument in Washington Monthly . "Most experts believe that the mullahs' days are numbered, and that true democracy will come to Iran," he observed. "That day will arrive sooner, the hawks argue, with a democratic Iraq on Iran's border. But the opposite could happen," he added. "If the mullahs are smart, they'll cooperate just enough with the Americans not to provoke an attack, but put themselves forth to their people as defenders of Iranian independence and Iran's brother Shi'a in southern Iraq who are living under the American jackboot. Such a strategy might keep the fundamentalists in power for years longer than they otherwise might have been."

As it became clear that the Iraq War would prove much more difficult than its advocates imagined, the mainstream media began recognizing how vulnerable U.S. foreign policy had become to Iranian influence. David Ignatius wrote this in February 2004:

The United States is "stuck in the mud in Iraq, and they know that if Iran wanted to, it could make their problems even worse," Rafsanjani said in an interview with the Tehran daily Kayhan. He coyly opened the door to a Washington-Tehran dialogue about Iraq and other issues, saying, "For me, talking is not a problem." The hard-line mullahs in Tehran are sitting pretty these days: America has toppled their historical foe, Saddam Hussein, and is struggling with a nasty postwar insurgency. Meanwhile, an Iranian-born Shiite cleric, Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani, has emerged as the dominant figure in the new Iraq. ... Anyone in the White House who imagines that the Iranians are running scared because more than 100,000 U.S. troops are bivouacked next door hasn't been reading the papers. From Iran's standpoint, the United States is pinned down and vulnerable. And because of Tehran's overt and covert influence among Iraq's Shiite majority, the mullahs may actually be in a position to shape the terms and timing of America's departure.

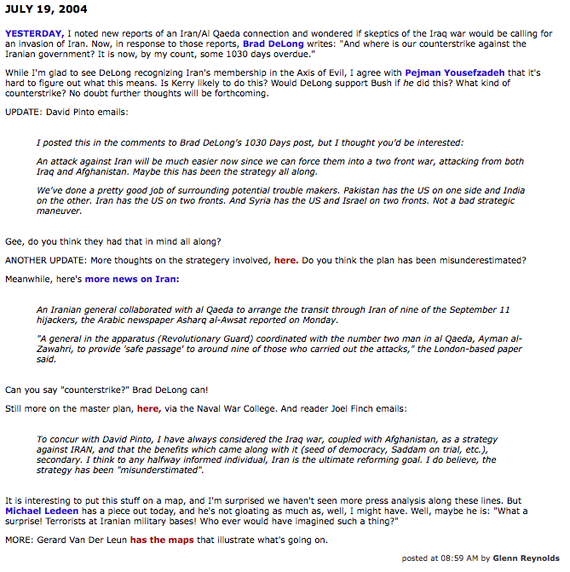

Meanwhile, in the right-leaning blogosphere, Instapundit and his readers still felt confident not just that the Bush administration was winning the war in Iraq, but that it was all part of a brilliant plan to surround and conquer the regime in Iran.

Take this July 19, 2004 post :

All these years later, it's clear that hawkish analysis and the conventional wisdom that it shaped was dead wrong. Invading Iraq did not strengthen America's hand with Iran. Rather, it gave Iran geopolitical leverage over the United States even as it enabled that country to contribute to the deaths of U.S. troops with impunity. As AP reports that Iran's influence in the region is reaching unprecedented levels, the foreign-policy lesson isn't that hawks were wrong, though they were, or that Iran's new strength imperils America. (I have no idea if it does.)

The lesson is that Americans vastly overestimate their ability to develop grand strategies and to predict how foreign interventions of choice will play out over time. This has led the United States to treat war as a viable means of shaping the world rather than as an option of last resort that has wildly unpredictable consequences. You'd think that the business of making confident predictions about wars of choice would be discredited by now, given how often prominent elected officials and foreign-policy commentators have been wildly wrong in recent years.

But even after Iraq, Afghanistan, and Libya, confident predictions by hawks remain a prominent feature of our foreign-policy debate, even when it comes to Iran.

When will America learn?