U.S. Marine Corps Maj. Matt Breen, right, helps an Iraqi army soldier identify advantages of micro-terain during squad tactics training on Al Asad Air Base, Iraq, Jan. 15, 2015. U.S. Army photo by Sgt. William White

The War America Doesn't Want To Own

In his State of the Union adddress, Obama asked Congress and the public to support a campaign that none of them want to own—not even him. By Uri Friedman

Tuesday's State of the Union address was the first since 2001 to not mention al-Qaeda. It opened with the promise of a post-post-9/11 era. "We are 15 years into this new century," President Obama observed . "Fifteen years that dawned with terror touching our shores; that unfolded with a new generation fighting two long and costly wars."

"But tonight," he added, "we turn the page."

It was an odd way to preface a request for Congress to bless a new U.S. military offensive against a terrorist group in the Middle East. What followed was, as my colleague Peter Beinart described it , possibly "the briefest and most half-hearted call to war in American history." It's a war (or " targeted operations ," or a " comprehensive and sustained counterterrorism strategy ," depending on your preferred terminology) that is now in its 167th day, even as almost no one—not the president, not Congress, not many Americans—seems to have much appetite to fight it.

After boasting that the U.S. had halted the Islamic State's advance in Iraq and Syria, promising not to get "dragged into another ground war in the Middle East," and pledging to "degrade and ultimately destroy" ISIS, Obama directed his attention to the lawmakers seated before him: "I call on this Congress to show the world that we are united in this mission by passing a resolution to authorize the use of force against ISIL." Departing from his prepared remarks, he added , "We need that authority."

The comments captured Obama's profound ambivalence about the military campaign that he's launched against ISIS, which, as it happens, goes by the name " Inherent Resolve ." He vowed to "destroy" ISIS, but only if doing so doesn't require ground troops. He framed his outreach to Congress more as a PR move than a legal necessity—an effort to "show the world that we are united in this mission." But then, in his impromptu remarks, he suggested that the operation's current legal foundation is shaky—that it needs congressional sanction.

In the absence of congressional authorization, the Obama administration has rested the legal case for its offensive against ISIS on the 2001 Authorization for the Use of Military Force (AUMF). It's done so even though that resolution authorized force against "those responsible" for the 9/11 attacks, a clause typically interpreted as referring to al-Qaeda and its "associated forces," and not ISIS, a next-generation jihadist group that is in fact a rival of al-Qaeda's. And it's done so even though Obama called for repeal of the 2001 AUMF as recently as 2013—in order to place legal restrictions on America's freewheeling counterterror activities , and remove the country from its "perpetual wartime footing."

Jack Goldsmith, a Harvard Law professor and former Bush administration official, believes Obama's call for Congress to authorize force against ISIS isn't sincere. Writing the morning after the State of the Union, he noted that the administration hasn't submitted draft language for a new AUMF to Congress, as the Bush administration did in 2001. But he also speculated that the U.S. government's expansive use of the 2001 AUMF since 9/11 may have had a chastening effect on Obama, who is wary of releasing another vaguely worded authorization into the wild:

[P]art of it, I suspect, is that the President does not want his legacy associated with a new AUMF that extends the endless war against Islamist terrorists legally, conceptually, and geographically. ... Rhetorically, the President says he wants a new AUMF. But rhetoric accompanied by non-action suggests that he wants to run out the clock without being burdened by one.

Scarred by seemingly endless war but startled by the ruthlessness and expansion of ISIS, Americans are similarly ambivalent about how to confront the jihadist group. A Brookings poll conducted in November found that 70 percent of Americans view the Islamic State as the top threat to American interests in the Middle East. But they held conflicted, even contradictory, views about how to respond to its rise. Fifty-seven percent of respondents opposed dispatching U.S. ground troops to fight ISIS, but 57 percent also said the U.S. should do whatever is necessary to defeat the group. At the same time, nearly the same percentage questioned the very feasibility of destroying ISIS, stating that even if the group were to be defeated, ISIS or a similar group would experience a resurgence once U.S. military operations ended.

U.S. lawmakers have yet to co-sign the campaign as well. Some, like Senator Tim Kaine, the Virginia Democrat, have drafted new AUMFs rather than wait for the White House's version. But—amid doubts about the campaign's prospects and the administration's strategy, and divisions between Democrats and Republicans over issues like deploying ground troops and targeting the Syrian military—the proposals have made little progress so far. Congress and the White House, notes Josh Keating at Slate, are "locked in an awkward dance," but a mutually beneficial one: The White House can invoke the old AUMF to justify its campaign while blaming the lack of a new authorization on Congress, and members of Congress can avoid taking ownership of a war that might not succeed. (On Wednesday, House Speaker John Boehner suggested that the House would take action on a new AUMF sometime this spring—if the president sent over a draft.)

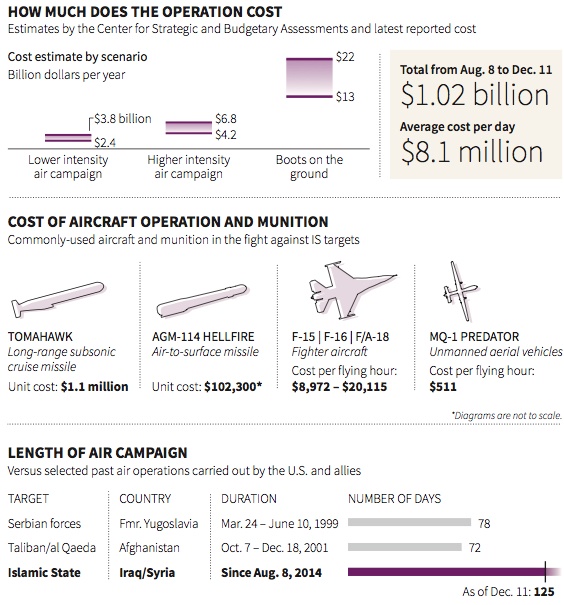

In the meantime, the operation against ISIS continues. In the five-plus months since it began, the U.S.-led campaign —which has involved nearly 2,000 airstrikes and the authorization of more than 4,000 U.S. advisory troops for Iraq and Syria—has cost more than $1 billion and the lives of three U.S. soldiers . Here's a breakdown of some of the expenses involved, as of early December:

The Cost of Fighting ISIS

The "next page" that Obama referred to on Tuesday night, it seems, is a counterterrorism campaign in legal limbo, with no clear champions or endgame. John Kennedy once said "victory has 100 fathers, and defeat is an orphan." In a way, the U.S. campaign against ISIS is already an orphan, even before war is formally declared.