sponsor content What's this?

Global Snapshot: The Asia-Pacific Defense Environment.

Presented by

Forecast International

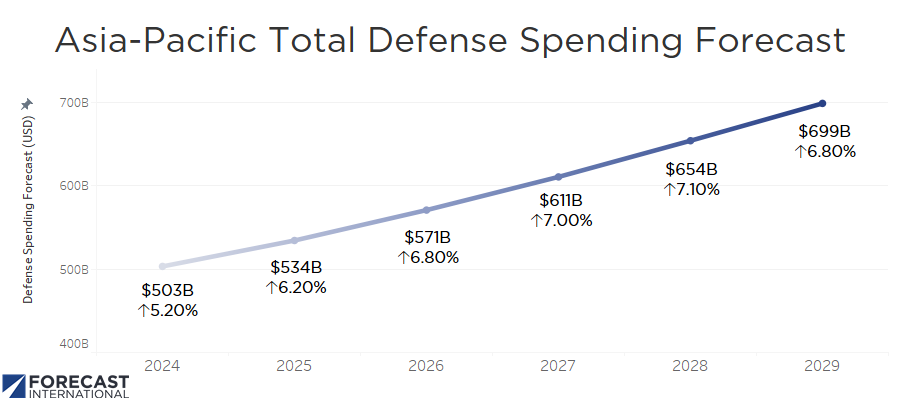

The Asia-Pacific region represents arguably the most dynamic defense market in the world. China serves as the instrumental element in Asia-Pacific defense market growth, and with the world's second-largest defense budget, continues to set the pace for the region.

That pace – and its strategic security implications – has a profound ricochet effect on the rest of the regional actors.

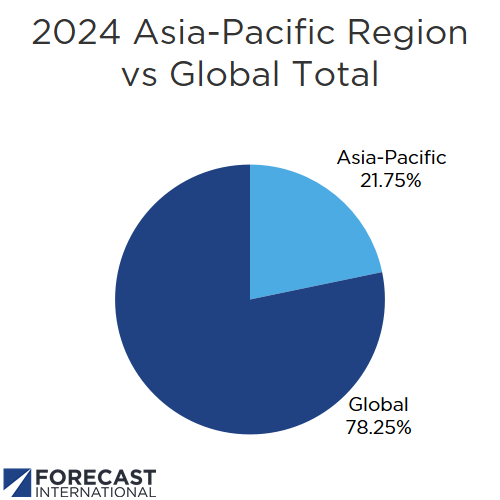

Due to its geopolitical underpinnings, significant demographic pools, and still-developing economies, combined with the slow but steady shift in global wealth from West to East, the Asia-Pacific defense market constitutes roughly 22 percent of total global military expenditures.

China's defense expenditures currently amount to 46 percent of the regional total, with its principal regional rivals – India, Japan and Taiwan – combining for another 26 percent.

While some of the smaller Asia-Pacific nations are hedging their alignment between China and the United States, or are still relying upon the U.S. presence to ensure the status quo, most countries in the region are revisiting their national security approaches with an eye on adding newer, upgraded weaponry and an even larger capacity of inventory.

This ensures that foreign vendors are granted ample opportunities in the region, but also allows local industries to reap the benefits of offset, workshare, and technology transfer arrangements within major defense deals. The latter are more and more the norm as regional governments seek to harvest side benefits from large-scale acquisitions and in turn grow their local industries in order to wean their militaries of dependence on foreign supply – a key strategic vulnerability.

Not only China but increasingly Japan, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan are becoming more self-sufficient in areas of defense technologies. India, too, continues to push for greater shares of indigenous capability in its military inventory in order to diminish its overwhelming dependence upon foreign-sourced supply (roughly 65-70 percent of its inventory). Defense industrial bases of smaller, but growing, capability are being cultivated across a broad spectrum of regional nations, including Australia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam.

This indicates a potential future in which the region becomes less dependent on foreign-sourced technologies and more a cooperative research and development partner with foreign nations, and/or approaches a net balance (or surplus) on the export-import ledger.

Map.png)

At over $230 billion in 2024, China is the second-largest nominal defense spending nation in the world behind only the United States. It should be noted that many experts believe that China's cumulative defense budget is far higher than official figures provided by Beijing. Elements such as military technological research and development and even some major weapons purchases are kept off-budget, thus raising actual defense investment figures to well beyond the official topline number published by the Chinese state.

Further, when factoring purchasing power parity into an examination of China's defense spending, the "bang for the buck" Beijing wrings from its spending is significantly higher than a sheer dollar figure, as internal costs of production and purchasing are not tied to currency exchange rates and the salaried cost of maintaining a large standing military is less for China than it is for NATO members.

India’s defense budget is the region’s second-largest. When excluding pensions, it accounted for nearly $58 billion in 2024. The country boasts the world’s third-largest standing military. The Indian Armed Forces are tasked with countering a potential collusive threat from the country’s neighboring nuclear-capable foes, China and Pakistan.

But with China spending three times per year what India does on its military, keeping relative pace with Beijing becomes ever more difficult. In 2024, year-on-year nominal defense budget growth for China reached 7.5 percent versus 4.9 percent for India.

A further issue for India is how much of its capital expenditure (37 percent of its overall budget in 2024) continues to be invested in foreign material, despite decades-long efforts at increasing the indigenization content of its military hardware. With broad modernization requirements across all domains, generating the most return on investment is crucial to ensuring the Indian military features qualitative technological par with China.

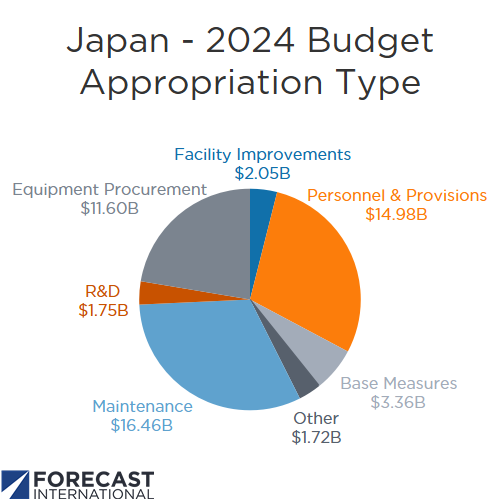

Japan continues to rapidly increase its topline defense spending levels since launching a Defense Buildup Plan (DBP) in December 2022. The DBP calls for spending JPY43 trillion ($300 billion) - an average of $60 billion per annum - from 2023 through 2027. The ultimate aim is to bring defense budgetary levels up to 2 percent of GDP from the country’s longstanding informal cap of 1 percent or less of annual GDP earmarked for the military budget. By effectively doubling its defense budget Japan will remain one of the highest military investors in the Asia-Pacific and the world.

While the increases in defense spending are noteworthy, Japan does face headwinds in terms of its currency, the yen. By June 2024, the Japanese yen had plummeted to its lowest value against the U.S. dollar since 1986. That declining value eats into the Japanese defense budgets buying power as many of its procurements involve U.S.-designed platforms or key equipment parts for Japanese-produced systems which are sourced from the U.S. and other countries. Those sales are conducted in U.S. dollars and other foreign currencies such as the Euro. A weakened currency therefore undercuts the scale of what Japan can purchase and negates to a degree any upticks in defense funding.

The next largest military investors in the region are South Korea and Australia. For 2024, the topline defense budgets for these countries totaled $43.9 billion and $36.7 billion, respectively. Combined the two nations accounted for 16 percent of the total military spending in the Asia-Pacific region.

In the case of Australia, overall defense funding under the country’s latest Integrated Investment Program (IIP) is planned for AUD765 billion ($486 billion), or AUD76.5 billion ($48.6 billion) per annum, through fiscal year 2033-34.

The other significant defense spender in the region is Taiwan, which earmarked $19.37 billion towards its armed forces and overall security in 2024. To maximize its defense investment against the island nation’s strategic threat from China, asymmetrical defense capabilities are being emphasized to counter Beijing's use of "gray zone" tactics, while improving its capabilities in C5ISR (Command, control, communications, computers, cyber, intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance), electronic warfare and long-range strike. The establishment of a comprehensive, multi-layered air defense approach is also being prioritized, as well as resiliency versus a potential first-strike attack by China.

Interspersed amongst the larger markets are the ASEAN countries, whose defense spending cumulatively reached over $50.6 billion in 2024, or around 10 percent of the Asia Pacific region’s military expenditure.

Within this subset of the Asia-Pacific region, Singapore is the leading defense market, devoting over 2.8 percent of GDP to its military, resulting in an annual defense budget of over $15.6 billion. The Indonesian government maintains a military budget of almost $8.9 billion, while Vietnam has grown its defense expenditures to nearly $7.5 billion. Though with comparatively smaller defense budgets, the ASEAN countries tend to be the fastest growers in Asia-Pacific, with Vietnam, Brunei, the Philippines, Malaysia, and Cambodia all increasing their defense budgets by double-digit figures in their respective FY24 spending plans.

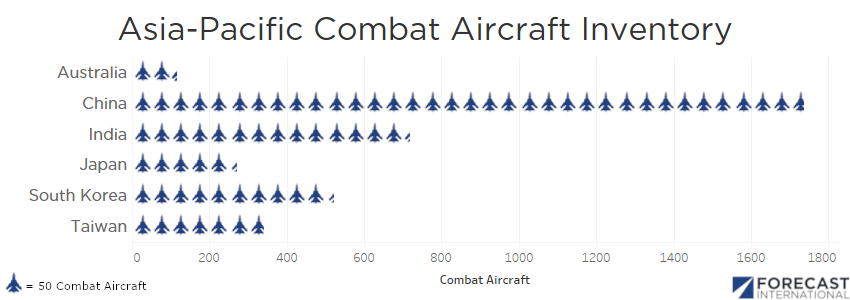

Chinese defense spending vastly outpaces that of its peers, and Beijing is similarly able to maintain sizable numerical advantages in the military equipment it puts into service. Well over 1,500 fighter jets are on duty with the PLAAF, more than double the fleet available for the Indian Air Force, the next-largest air competitor in the region. While many of the PLAAF’s fighter jets are older models, the Chinese defense industry is increasingly developing combat aircraft of greater sophistication – emphasized by the maiden flight of a new sixth-generation design in December 2024.

As China modernizes its air combat fleet, its neighbors are responding with their own fighter jet programs. Australia, Japan, and South Korea have all inducted the F-35 into service, with Singapore soon to follow. India continues to covet the F-35, as well, while simultaneously pursuing the procurement of over 100 fourth-generation jets through its MRFA project. Additionally, South Korea is wrapping up the initial manufacturing phase for its first batch of new twin-engine, 4.5-generation multirole fighters, the KF-21 Boramae.

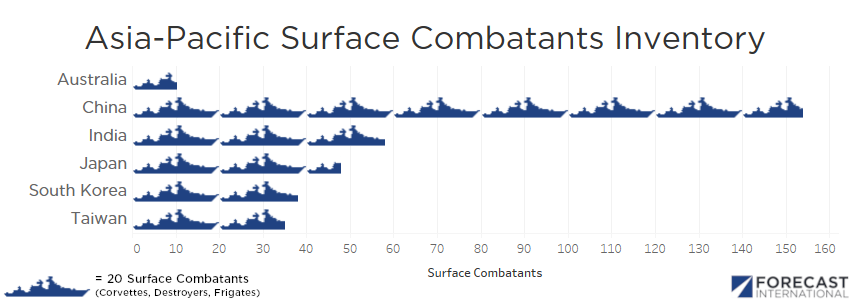

As it develops its airpower, Beijing has also invested heavily in its maritime power projection, enabling the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) to maintain an aggressive posture in disputed waterways. According to the Pentagon’s most recent annual report to Congress on China’s military strength, the PLAN has the largest fleet in the world at over 370 total ships, more than 140 of which are major surface combatants.

The PLAN’s rapid modernization has spurred China’s neighbors to address the state of their own navies and introduce ‘blue-water’ capabilities. Australia has launched a multiyear project to support fleet renewal and expansion, expecting to spend $35.6 billion on new surface combatants and submarines across the upcoming decade. The Japanese Navy is in the process of inducting new Mogami-class frigates into its fleet, and in October 2024 the Ministry of Defense inked a contract for a new pair of ASEV ballistic missile defense destroyers. The Indian Navy has over 130 surface ships of varying types and classes, with an additional 67 warships currently under construction.

This content is made possible by our sponsor General Atomics Aeronautical Systems; it is not written by and does not necessarily reflect the views of Defense One editorial staff.

NEXT STORY: Global Snapshot: The Middle East and North Africa Defense Environment