RIA Novosti/AP

The Strategy Behind Russia's Takeover of Crimea

Moscow has supported secessionist movements in ex-Soviet states to expand its influence in the region. Is the Crimean crisis just the latest example? By Uri Friedman

It seemed like a classic example of euphemistic bureaucrat-speak when, on Friday, U.S. officials referred to the deployment of Russian troops in Crimea as an "uncontested arrival" rather than an invasion.

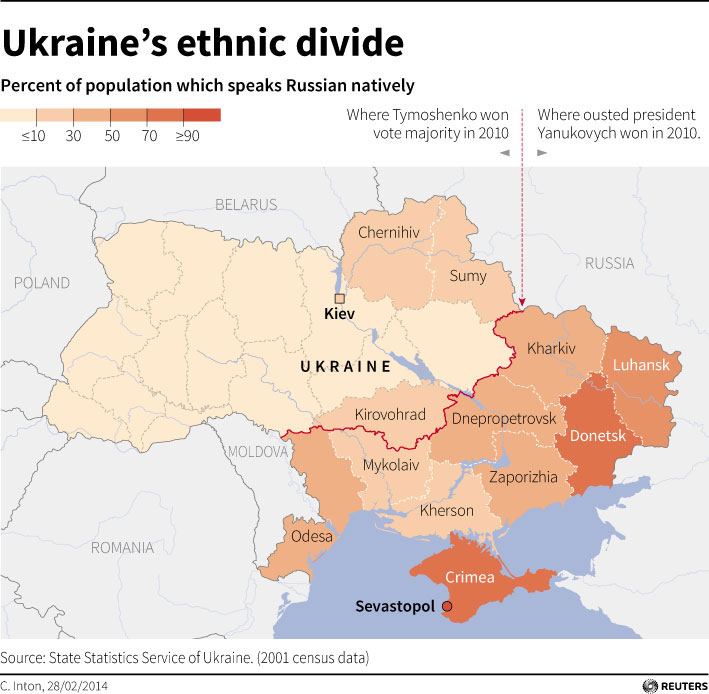

But terminology matters here. Take the word "uncontested": The southern peninsula of Crimea, which the Soviet Union transferred to Ukraine in 1954 and which now hosts the Russian military's Black Sea Fleet, is the only region in the country where ethnic Russians are a majority (60 percent of a population of 2 million). And a good number of them favor closer relations with, if not outright annexation by, Moscow; according to one recent poll, 42 percent of Crimean residents want Ukraine to unite with Russia. That doesn't mean there are no Ukrainian nationalists or Kremlin opponents in Crimea—there certainly are—but it does mean many people in the autonomous republic, spooked by the ouster last week of Ukraine's pro-Moscow President Viktor Yanukovych, welcome Russian military intervention.

Or take the word "arrival": If this is an invasion, it's a disorienting and not yet fully formed one. There were the shadowy, Russian-speaking gunmen who fanned out across Crimea on Friday, seizing government buildings and airports. And then there was the series of seemingly orchestrated events on Saturday: Crimea's freshly minted prime minister pleading for Russian help; Russia's lower house of parliament urging Vladimir Putin to "stabilize" Crimea, the Russian president obliging; the upper house swiftly granting him the authority to use force in Ukraine. Putin is pledging to make his next move soon, as his military masses and the White House fumes. All told, we're now witnessing what Reuters is calling the "biggest confrontation between Russia and the West since the Cold War."

So what should we call the worrying developments in Ukraine? And what is Putin thinking? Back in 2008, Thomas de Waal, an expert on the South Caucasus, argued that Putin's greatest legacy is something de Waal called "soft annexation," which, at the time, was underway in Georgia's breakaway provinces of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. The idea, expressed in various forms over the years, is that Russia is pulling political, economic, and military levers—all of which fall short of traditional invasion—to exploit ethnic conflicts in countries that used to be in its orbit. And the goal is to leverage these tensions, which are often relics of the Soviet Union's messy consolidation and collapse, to gain influence in former Soviet states, while preventing these countries from moving closer to the West.

When, for instance, Ukraine was considering a treaty with the European Union earlier this year, Fiona Hill and Steven Pifer of the Brookings Institution penned a prescient memo warning of ways Russia could retaliate politically and economically against Kiev:

Putin perceives the European Union as a genuine strategic threat. The threat comes from the EU’s potential to reform associated countries in ways that pull them away from Russia. The EU’s Association Agreements and DCFTAs are incompatible with Putin’s plan to expand Russia’s Customs Union with Belarus and Kazakhstan and create a “Eurasian Union.” Putin’s goal is to secure markets for Russian products and guarantee Russian jobs. He also sees the Eurasian Union as a buffer against alien “civilizational” ideas and values from Europe and the West....

Moscow could take actions that weaken the coherence of the Ukrainian state, e.g., by appealing to ethnic Russians in Crimea, or even by provoking a violent clash in Sevastopol, leading to the deployment of Russian naval infantry troops from the Black Sea Fleet to “protect” ethnic Russians.

One of the most consequential questions now is whether Putin's gambit in Ukraine will follow the model of Russia's previous support for secessionist movements in former Soviet states (and particularly in the Black Sea region), or whether it represents a break with that approach.

The Moldovan prime minister, for his part, sees in Ukraine's crisis echoes of Moscow's backing of the breakaway province of Transnistria, another pro-Kremlin territory with a large ethnic Russian population. In the early 1990s, Transnistria declared independence from Moldova, sparking a brief war between a complex constellation of regional forces that included a Russian military unit known as the 14th Army. Russia now stations troops on the wisp of land along the Ukrainian border, and provides Transnistria with financial assistance. Negotiations to resolve its status are frozen.

Many others are comparing the current situation to Russia's intervention in Georgia in 2008 over Abkhazia and South Ossetia, which also have small ethnic Russian populations. Russia sent peacekeepers to the territories, and dispatched its military to ostensibly protect those troops when Georgia tried to reclaim South Ossetia by force in the summer. That war lasted five days and left Russia in control of the provinces, both of which are now home to Russian military bases.

There are several similarities between these cases and that of Crimea: the separatist rumblings in ex-Soviet states turning away from Russia, the appeals of ethnic Russians in the territories for the Kremlin's help, the forward deployment of Russian troops. In the lead-up to the latest standoff, for instance, the Russian consulate in the Crimean capital of Simferopol had stoked controversy by issuing Russian passports to ethnic Russian Crimeans—a practice Moscow also employed in South Ossetia ahead of the conflict there.

"The Russians raised the stakes and baited [former Georgian President Mikheil] Saakashvili .... by effecting a 'soft annexation' of South Ossetia," de Waal wrote as war between Georgia and Russia broke out in 2008. "Moscow handed out Russian passports to the South Ossetians and installed its officials in government posts there. Russian soldiers, although notionally peacekeepers, have acted as an informal occupying army."

Putin himself, however, has dismissed these comparisons. When asked by a reporter in December whether Russia would deploy troops to Crimea in a Georgia-like scenario, he dismissed the analogy as "invalid":

[I]n order to stop the bloodshed, as you know, there were peacekeeping forces in [Abkhazia and South Ossetia] that had international status, consisting mainly of Russian troops, although there were also Georgian troops and representatives from these then-unrecognised republics. In part, our reaction was not about defending Russian citizens, although this was also important, but followed the attack on our peacekeeping forces and the killing of our troops. That was the essence of these events.

Thankfully, nothing similar is happening in Crimea, and I hope never will. We have an agreement on the presence of Russia’s fleet there. As you know, it has been extended–I think, in the interest of both states, both nations. And the presence of the Russian fleet in Sevastopol, in Crimea, is in my view a serious stabilising factor in both international and regional policy—international in a broad sense, in the Black Sea region, and in regional policy.

Fast-forward two months, though, and the situation has changed dramatically. Putin's ally in Kiev has been removed from power. A new, pro-Europe Ukrainian government has taken shape. The future of the Crimean base for Russia's Black Sea Fleet, which is crumbling but still important for Russia's naval power in the Black Sea and Mediterranean, is in jeopardy. And, just like Russia did in Georgia, Putin is now justifying the use of force in Ukraine as a means of protecting "the life and health of Russian citizens and compatriots on Ukrainian territory," including Russian troops.

Still, Russia's recent moves don't necessarily mean that it will go as far as a Georgia-style "soft annexation." De Waal himself pointed out on Friday that Crimea (population: 2 million) is far bigger than Abkhazia (population: 240,000), South Ossetia (population: 70,000), and Transnistria (530,000), and that secessionist sentiment is less widespread in Crimea than in these other provinces. In threatening force in Ukraine, he wrote, Russia may primarily be trying to secure its naval base and destabilize the Ukrainian government, not set the stage for annexation or invasion:

Any Russian escalation deserves a strong response from the West. But if you read what Putin is actually saying he is being more equivocal. He is ruthless, but he is not Sauron in Lord of the Rings. He almost certainly wants the government in Kiev to fail, but he is also hosting the G8 summit in Sochi in June....

Russia has one overwhelming strategic asset in Crimea: the Black Sea naval base in Sevastopol. My guess is that Putin’s main goal in Crimea is to maintain that base at all costs.

If the Crimean crisis is fundamentally a show of strength by Putin to preserve his naval base in Crimea, and remind Ukraine's government that Moscow can still knock it off balance, what explains Putin's willingness to make such a bold move in the first place—one that could still potentially mushroom into a larger conflict?

In 2006, Nicu Popescu, an expert on EU-Russian relations, offered one of the best analyses I've seen of Russia's new assertiveness in world affairs under Putin. Moscow's support for secessionist movements in Georgia and Moldova, he said, was part of Russia's larger decision over the past decade to make expanding its influence in Eurasia, not creating favorable conditions for domestic economic growth, the top priority of its foreign policy. There are four reasons for this shift, Popescu argued:

- The growth of Russia's economy due to oil and gas exports, which helps bankroll a more aggressive foreign policy

- The Kremlin's centralization of power, which neutralizes the challenges posed by political opponents at home

- The retreat of the West from the world stage after the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, which creates an opening for Russia

- The success Russia has had in suppressing its own secessionist movement in Chechnya, which makes it easier for the Kremlin to support secessionist groups abroad

"These have all led to a feeling in Moscow that Russia has the resources and the proper international conditions to reassert its dominance in the former Soviet Union," Popescu wrote. "Stepping up support for the secessionist entities is seen as a way to achieve that."

And if Russian leaders believe they can do so, in Crimea and elsewhere, without provoking a major response from the West , they seem willing to assume the risk that comes with it.