ISIS fighters participate in a military parade in the northeastern Syrian city of Raqqa, on June 30, 2014. Raqqa Media Office/AP

There Is No Global Jihadist ‘Movement’

The world of Islamist fighters is deeply fragmented and constantly shifting.

Reports last week indicated that the Nusra Front, a major anti-Assad jihadist group, might be abandoning its affiliation with al-Qaeda due to a combination of leadership losses and internal dissent, though a Nusra spokesman has since denied that development. The group, otherwise known as Jabhat al-Nusra, was first formed in Syria as an independent affiliate of both al-Qaeda and ISIS, which were then allies. When al-Qaeda and ISIS parted ways, Nusra established itself as a rival to its former Islamic State sponsor out of loyalty to al-Qaeda. Even with that defection, however, the self-proclaimed Islamic State is becoming increasingly attractive to other members of the jihadist universe, with Boko Haram the latest group to sign on.

Such kaleidoscopic patterns are not uncommon: What’s sometimes referred to as the global jihadist “movement” is actually extremely fractured. It’s united by a general set of shared ideological beliefs, but divided organizationally and sometimes doctrinally. Whether to fight the “near enemy” (local regimes) or the “far enemy” (such as the United States and the West), for example, has been contentious since the 1990s, when Osama bin Laden declared war on the United States. Rivalry among like-minded militant groups is as common as cooperation. Identities and allegiances shift. Groups align and re-align according to changing expectations about the future of the conflicts they’re involved in, as well as a host of other factors, such as competition for resources, leadership transitions, and the defection of adherents to rival groups that appear to be on the ascendant.

Governments combating terrorist groups can seem blind to these complications, especially to the consequences of weakening one group at the expense of another. When a state faces multiple terrorist adversaries—and there are almost always several different ones—encouraging splintering and factionalism, by killing top leaders for example, is not always the best option for reducing violence in the long run. Since at least the 1998 bombings of the American Embassies in East Africa, the U.S. has worked to undermine al-Qaeda, a campaign given new urgency and momentum after 2001. That goal has largely been accomplished if one thinks of al-Qaeda as the original organization Osama bin Laden founded around 1988. However, one affiliate (al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula), one former affiliate now transformed into a rival (the Islamic State), and one potentially soon-to-be ex-affiliate (the Nusra Front) have emerged as formidable successors. And jihadist groups—some affiliated with al-Qaeda, some not—have proliferated in Africa and Asia.

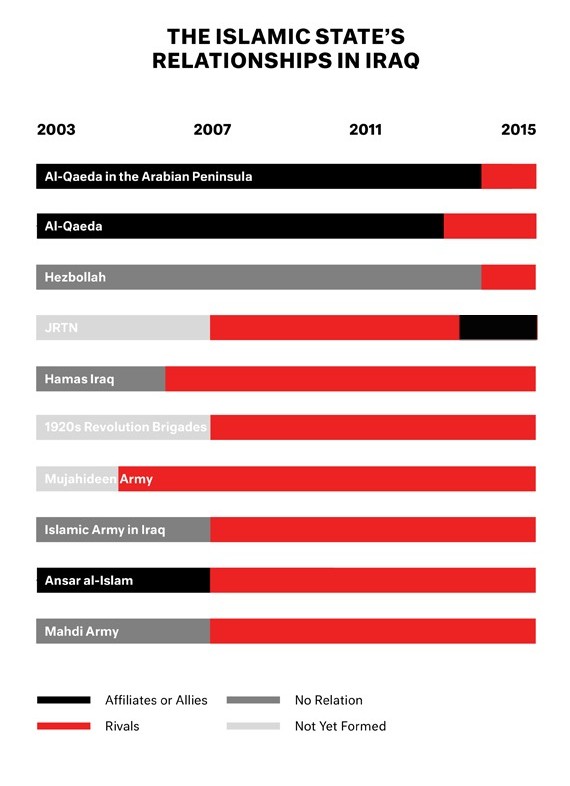

What threatens American national security now, after more than a decade of U.S. operations against al-Qaeda, is primarily the rise of the Islamic State as a competitor to al-Qaeda and its allies of the moment. As the diagram below shows, the Islamic State's relationship to al-Qaeda and other groups has shifted over time.

Kara Gordon (Data: Martha Crenshaw, Mapping Militant Organizations, Stanford University)

Under the leadership of its founder, Abu Musab al-Zarqawi (a Jordanian), the group joined bin Laden’s campaign shortly after the American invasion of Iraq in 2003. Known then as al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI), it tried to dominate other Sunni groups fighting there but instead, through its ruthless tactics, provoked them to turn against it. At the same time, AQI also clashed with al-Qaeda central, which objected to its brutality (including videotaped beheadings) and acute sectarianism. Local disaffection, combined with the coalition military surge and perhaps Zarqawi’s death at the hands of the American military in 2006, caused the group to lose influence even though it rather grandly retitled itself the Islamic State of Iraq (ISI) at around the same time. This move was probably an effort to boost legitimacy and counter critics who accused AQI of being controlled by foreigners, but in hindsight the name change seems an important clue to the group’s intentions. By the time the Islamic State’s current leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, took over in 2010, ISI was a seriously weakened group that had lost most of its top leadership.

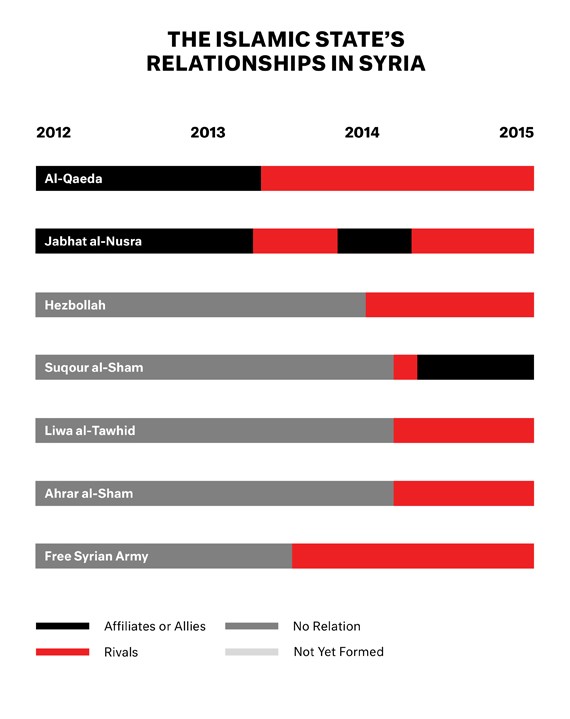

But after the withdrawal of foreign military forces from Iraq in 2011, ISI began to regain ground there in a much less pressured security environment. The outbreak of civil war in Syria in the same year provided ISI a new opportunity for expansion, which in turn led to the dissolution of its alliance with al-Qaeda central, as the following diagram of militant group relationships in Syria shows.

Kara Gordon (Data: Martha Crenshaw, Mapping Militant Organizations, Stanford University)

Showing some initiative, ISI set up the Nusra Front as its Syrian affiliate in 2011, attempting to absorb the group fully after renaming itself the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria in 2013. But the leaders of the Nusra Front rejected that merger. By 2014 Ayman al-Zawahiri, Osama bin Laden’s successor as the leader of al-Qaeda, had had enough of al-Baghdadi’s disobedience, including its attempt to take over the Nusra Front without consulting al-Qaeda central, and at that point the split between ISIS and al-Qaeda was final. Asked to choose between ISIS and al-Qaeda, Nusra essentially chose the latter.

The new ISIS was now pitted against the governments of both Iraq and Syria, an array of local groups in both countries, including elements of the Free Syrian Army—the loose coalition of secular, “moderate” rebel groups backed by the West—and the Kurdish pesh merga, as well as the Nusra Front and other al-Qaeda affiliates. Some important Syrian groups that had joined in the Islamic Front, a coalition of seven major Islamist groups whose ideology fell somewhere between that of the moderates and the jihadists, initially pledged allegiance to ISIS but later recanted. (To add to the confusion, rival groups occasionally cooperate on the battlefield, forming the kinds of tactical alliances that are not uncommon in such tangled conflicts.) Despite what seemed to be an unfavorable starting position, ISIS made impressive territorial gains in Syria and Iraq. By the spring of 2014 ISIS astonished the West by sweeping almost unopposed into Mosul, and in June the offensive culminated with the declaration of the caliphate under the aegis of the Islamic State, now no longer limited to Iraq and Syria.

A critical “unknown” as Iraq ramps up efforts to wrest back the territory it’s lost, with help from the U.S. as well as Iran, is how much local Sunni support the Islamic State can count on to consolidate its hold. The JRTN (Jaysh al-Tariqa al-Naqshbandia), for example, is a nationalist Sunni militant group with many former Baathists in its ranks. It opposed the jihadists during the occupation, although it was equally hostile to coalition forces. Yet despite ideological differences, it switched to supporting ISIS in 2013, apparently calculating that ISIS was now the winning party and that an alliance was the best bet for challenging hated Shiite rule in Iraq. What this means and how long the marriage of convenience will last are open questions. As the diagram of Iraq shows, during the U.S. occupation period the Islamic State’s predecessors failed to dominate other local Sunni groups, but the context is different now. Not only does ISIS appear to many other groups to be coming out on top among jihadist groups, it has also been utterly ruthless in destroying its opponents even if they are former allies.

A result of these fast-changing conflict dynamics is that the U.S. is engaged in a struggle for power in which the enemy of its enemy is not necessarily its friend. In the Islamic State as well as al-Qaeda and affiliates, the U.S. shares a common adversary with its enemies Iran and Syria. At the same time, actions against the Islamic State benefit al-Qaeda and affiliates, and vice versa. It may not be possible to weaken one without strengthening the other. “Moderate” rebels in Syria have not always stood up well against Islamist or jihadist factions. The only clear conclusion is that no solution is in sight.