Illustration by Ben Watson

In Ukraine, the US Trains an Army in the West to Fight in the East

For more than two years, some 300 American soldiers have been quietly helping train an enormous partner military in western Ukraine.

For more than two years, the U.S. military’s contingent of 300 or so soldiers have been quietly helping train an enormous allied military in western Ukraine. Meanwhile, Russian-backed separatists appear to be keeping pace some 800 miles to the east, showcasing entire parking lots full of new tanks and artillery just a 15-minute drive from the front lines.

“Every 55 days we have a new battalion come in and we train them,” said U.S. Army National Guard Capt. Kayla Christopher, spokesperson for the Joint Multinational Training Group-Ukraine, at Yavoriv Combat Training Center in western Ukraine. “And at the end of that 55-day period, we’ll do a field training exercise with that battalion.” The U.S. and partnered armies have trained seven battalions in the past roughly two years or so.

That’s what she calls the “main line of effort that you tend to see most of the time in the news.”

Building a host-nation’s military, the U.S. has learned painfully in the 21st century, has rarely been a good news story. And Ukraine’s conflict has largely taken a backseat to the sequel to one of those stories: the war on ISIS, in which eight Americans have lost their lives fighting since 2014. In the same period, Ukraine is believed to have lost nearly 4,000 soldiers to Russian-backed separatists.

Last week #OSCE SMM observed 283 weapons beyond withdrawal lines but outside of storage sites & 15-min drive from striking distance pic.twitter.com/GnaNd1aoGH

— OSCE SMM Ukraine (@OSCE_SMM) September 28, 2017

Since Crimea was annexed in 2014, the U.S. and partner militaries have helped grow Ukraine’s forces from just over 100,000 troops to nearly 250,000 today. Just since January, Capt. Christopher’s unit of 250 soldiers has added another 3,000 or so Ukrainian soldiers to Kiev’s ranks.

“But that's not the real end state,” she said. “Essentially, what we're trying to do is get them to the point where they are running their own combat training center,” like the U.S. Army’s National Training Center at Fort Irwin, Calif., or the Joint Readiness Training Center at Fort Polk, Louisiana.

In other words, their task is to build an army’s entire training infrastructure almost from the ground up — a tall order following decades of not-so-casual corruption that has plagued Ukraine’s and many post-Soviet countries’ militaries across eastern Europe.

“Our overall goal is essentially to help the Ukrainian military become NATO-interoperable,” Christopher said. “So the more they have an opportunity to work with different countries — not just the U.S., but all their Slavic neighbors, and all the other Western European countries that come” and train or exercise with Ukraine’s military.

That includes Poland, Estonia, Lithuania, Canada, and the U.K. The U.S. has also sent a variety of non-lethal military help to Ukraine — equipment like Humvees, medical supplies, bulletproof vests, and radars to track the hundreds of artillery shells that have fallen on the eastern Donetsk and Luhansk regions. Maybe Javelin anti-tank missiles, Defense Secretary Mattis said in August. But Christopher’s unit is far from the fighting. Their mission is “ training the trainers ” and in particular, adding to Ukraine’s NCO corps — the stern disciplinarians who help ensure that units are fit and ready for combat.

Terrorism in the east

For Ukraine’s new soldiers, combat means fighting terrorists — at least according to the U.S. military’s way of looking at things.

“They're called anti-terrorism operations rather than something else because of the issue with the Russian-backed separatists,” said Capt. Christopher. “So they're not really Russians, you know. They're essentially terrorists.”

So the U.S. calls eastern Ukraine’s most troubled regions an Anti Terrorism Operation zone, or ATO, where those Russian-backed forces have attacked and counterattacked Ukraine’s soldiers and civilians. (See, for example, this interactive day-by-day map of alleged shelling by Ukrainian government and separatist forces.)

In just the first two days of this month, UN monitors recorded dozens of violations to the Minsk II ceasefire, an agreement reached in February 2015 between Russia, Ukraine, France and Germany. The deal never really stuck. It called for all heavy weapons — tanks, rocket launchers and artillery — to be pulled away from the front lines and kept in monitored storage. By that time , more than 5,400 civilians had already been killed in the fighting. In the months after Minsk II was signed, the death toll barely slowed.

The Ukraine conflict, since 2014:

- At least 10,225 soldiers and civilians have died.

- Another 24,500 have been injured .

- Some 1.6 million have been displaced.

- Nearly 10,000 prisoners are believed to be held in the east. Last October, Kiev itself has said it was holding 500 or so prisoners of its own.

The UN calls these statistics “a conservative estimate based on available data,” and inevitably incomplete “due to gaps in coverage of certain geographic areas and time periods.” Military casualties, especially injuries, have been particularly under-reported, the UN says.

Most of the civilians killed in the fighting were killed by tanks and artillery, 55 percent; followed by IEDs, 36 percent; and small arms fire, 9 percent. For months it puzzled observers how allegedly local separatists could have obtained so much heavy weaponry, even factoring in Ukraine’s legacy as a sort of junkyard of old Soviet weapons factories. The appearance of more advanced equipment — drones and armored vehicles, for example — revealed Russia's hand in Ukraine as early as January 2015, although President Vladimir Putin didn’t admit Russia’s role until that December. Since then, their advanced equipment has only grown more sophisticated and deadly for Ukraine’s frontline soldiers.

International ceasefire monitors aren’t having an easy go of their job in 2017, either. During the first six months , they were restricted from or intimidated through armed confrontation (see photo below) inside regions mandated by the Minsk agreement no fewer than 480 times. More than 75 percent of those occurred in separatist-held areas.[photo]

(via the OSCE Special Monitoring Mission to Ukraine,

Sept. 2017

)

A world away

U.S. troops are largely kept away from the conflict. That is by design; the U.S. and the international community have struggled with the appropriate response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and annexation of Crimea.

Speaking alongside Ukrainian Prime Minister Petro Poroshenko in August, U.S. Defense Secretary James Mattis said, "We do not, and we will not, accept Russia's seizure of Crimea and despite Russia's denials, we know they are seeking to redraw international borders by force, undermining the sovereign and free nations of Europe."

So far, sanctions have been the U.S. and its European allies’ preferred response, hitting Russia’s major banks and energy companies. But President Trump has indicated that he feels sanctions may not be in the best interest of the U.S. In August, he complained about a new round of sanctions passed by Congress, calling it “seriously flawed.” But the measure reached the Oval Office with a veto-proof majority, and so he grudgingly signed it into law.

But that is a world away from the U.S. Army in Yavoriv, and even the fighting on the other side of Ukraine feels remote, Christopher said. “It's actually pretty remarkable how little you feel the effect of the conflict on the western side of Ukraine. It's almost as if nothing is happening,” she said. “And if I didn't work directly with soldiers every day, I don't think you would really know. I mean, we see it on the news every day, and I work with soldiers every day. So we know about it. But you go out into Lviv, or any of the other big cities around this area and you really don't feel the effects of there being war here.”

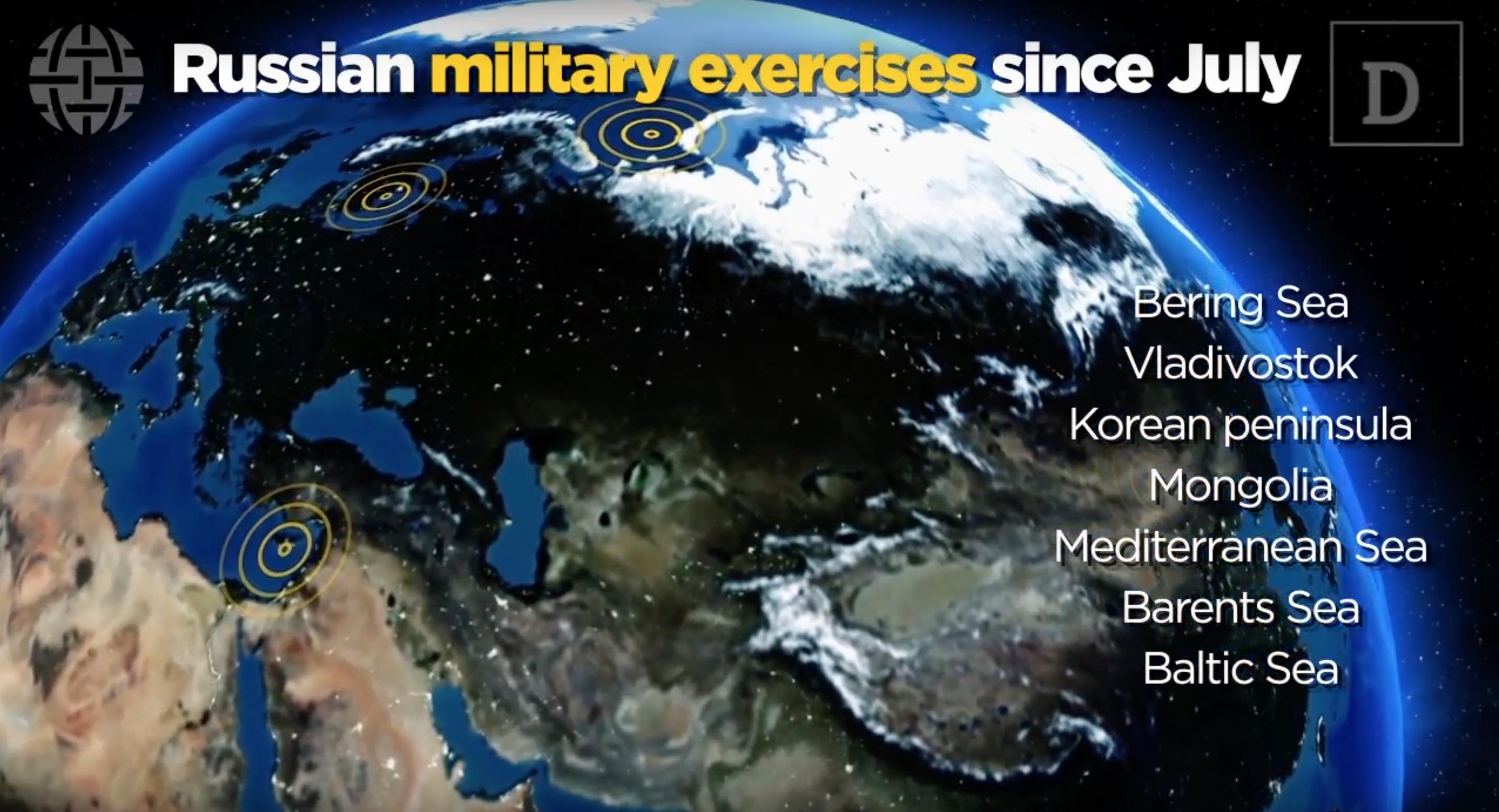

Except, perhaps, for the U.S. and NATO soldiers who for months have had their phones and social media accounts breached by what appear to have been Russian hackers. On top of that, Moscow has spent the past few months ferrying troops around its border with Ukraine and into Belarus for extended exercises that run from the Barents Sea to the Mediterranean.

So Russia is hardly backing down from a tense region. And apparently, neither is the U.S. Despite the Trump administration’s hesitancy , its approach in Ukraine is not terribly different from the Obama administration’s.

“The U.S. will continue to press Russia to honor its Minsk commitments and our sanctions will remain in place until Moscow reverses the actions that triggered them,” said Mattis in August during the visit with Ukraine’s Poroshenko.

For its part, Moscow’s latest move has been not to reverse its annexation of Crimea, but rather to fence off some 30 miles of land on the seized peninsula. One Russian lawmaker even said in May that Moscow would use nuclear weapons if the U.S. or NATO tried to enter Crimea.

Which would suggest that the U.S. Army’s quiet mission in Ukraine may go quietly on for many, many months to come.